04 Aug Storyteller

Raised in the heart of Blackfeet country, Jackie Larson Bread has a passion to share the story of her people and her culture

through the intricate art of beadwork. The landscape of her childhood has always been an indelible part of her art.

The Blackfeet Reservation lies high on the northern edge of Montana where the plains meet the Rocky Mountains and wildflowers bloom when winter gives up its brutal grip on Mother Earth. As a child, Jackie took it for granted that her family could pack a picnic and be deep in the mountains of Glacier National Park within a half hour. A favorite destination was Upper Two Medicine, a stunning landscape, although it had grizzly bears and she was scared of bears. It’s natural that her art is full of the Native symbolism of mountains, hills, plains, flowers, lakes, rivers, the morning star, tipis,

wolves, and yes, bear.

When she was a young girl in the 1960s her

people were highly traditional. She considered it a casual, rich way of life connected through the art of music, story, dance and ceremony, which all played out in her life. Her history, she says,

“was honed on the visual.” Jackie’s family lived in a rural setting about 10 miles from Browning — fairly isolated in that day and

time. Her grandmother, who died before Jackie was born, left a legacy of exquisite Blackfeet beadwork. As a little girl Jackie began to teach herself the delicate art of beading by studying those treasured pieces.

At 14, she had a summer job at the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning where she continued to work for 10 summers. She spent hours being with — living with — the history of her Native people. While working at the museum, Jackie began studying pre-20th-century Plains Indian beadwork. Beading is a proud and unbroken tradition of Native women from the Plains, Plateau and Great Basin regions of the United States and Canada. Tiny glass “seed” beads were introduced by Europeans to native people around 1840. Before that, they made beads of natural materials such as stone, bone and shells. Living close to the earth, Jackie describes their unspoken yearning to create beauty and the way each beaded piece is a unique and beautiful

work of art that tells its own story.

Jackie Bread received an associate of fine arts degree in museum studies and two-dimensional art from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe and a bachelor of fine arts in painting from the College of Santa Fe. The students at IAIA were taught by legends such as Otellie Loloma and Allan Houser and some graduates, too, have become legends. Jackie said, “We were all young people far from home with different traditions.” As students, they learned from each other and the friends she made there, 35 years ago, are still among her closest.

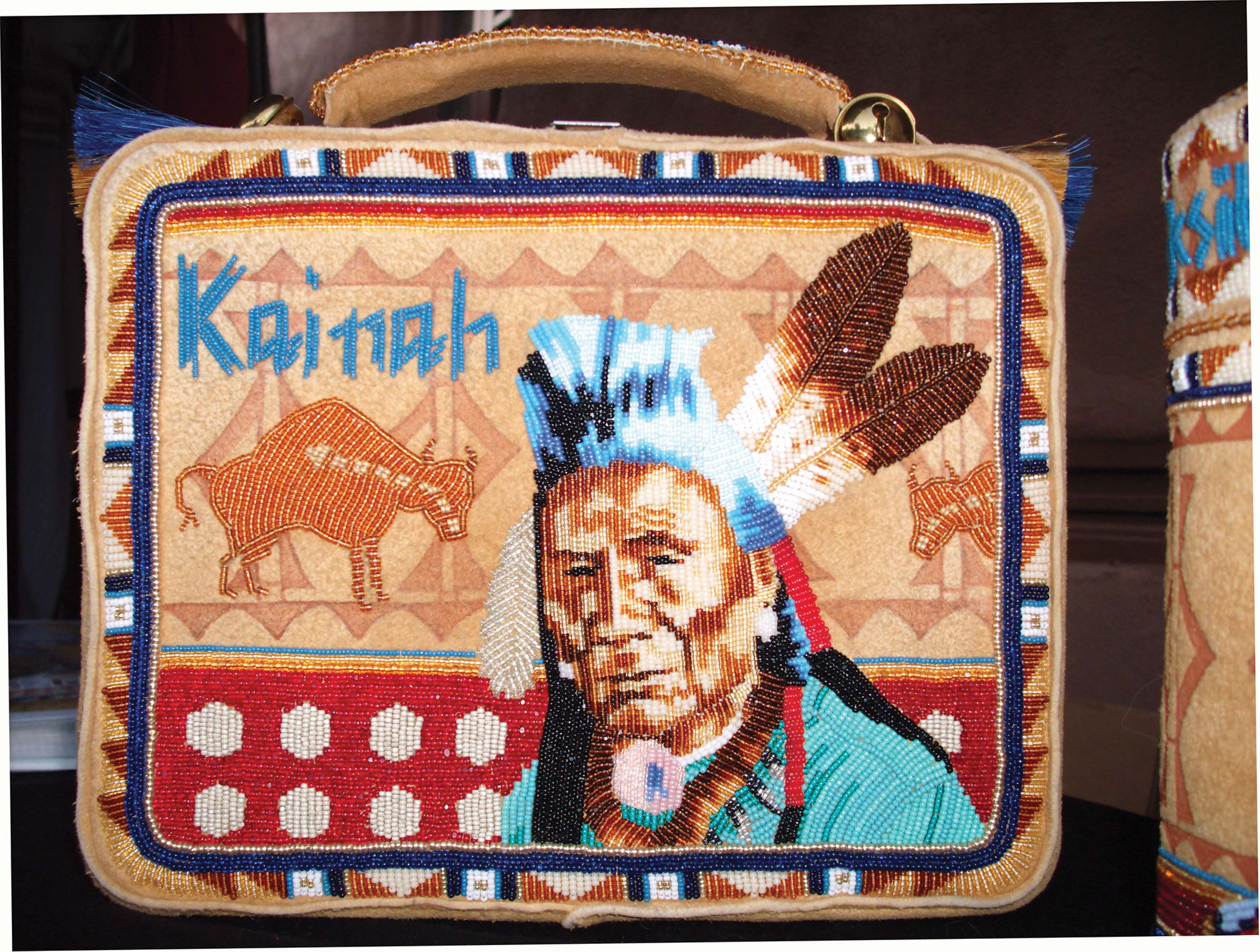

While at IAIA, Jackie’s focus was on painting and printmaking. Beadwork remained a passion and it was there she helped develop illusionary pictorial beadwork. With a background in fine art, she was able to successfully create dimension using graduated shades of beads to imbue a richness of color, light and shadow that is deep and tactile. The focus of her work today is beading portraits of her ancestors and her people and incorporating traditional Blackfeet design, imagery and symbolism. Jackie said, “Each bead in its place reveals how unique we are as a people and individuals. To the beautiful faces I often add bold traditional Blackfeet design, both geometric and floral that speaks of us so singular, so unique, so Blackfeet.”

Bead artists have a sense of community and mutual support. They alone understand the time and complexity of beading. Jackie credits

Joyce Growing Thunder Fogarty (Assiniboine/Sioux) from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in

Montana as pioneering the elevation

of beadwork to a recognized

artform within the last 30 years.

Jackie has worked with unceasing diligence over the years to create museum-

quality beaded art that is displayed across America, from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. to the Philbrook Museum of Art in Oklahoma, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas to the C.M. Russell Museum in Montana. Emil Her Many Horses

(Oglala/Lakota), curator in the office of

museum research at the NMAI, where

Jackie has served as a consultant, says,

“One trait that I admire about Jackie’s

beadwork, whether it’s her portrait style or

geometric beadwork, it’s distinctly Blackfeet.

She honors her cultural heritage through her

artwork.” Another unique aspect, he says, is that she has passed this trait on to her children, who are also great Blackfeet artists. Surrounded by a collection of Indian artwork for which she has traded, along with the art of her children, Jackie Bread works from home. She balances a commitment to her family and to her profession. Her husband, Norman Bread (Navajo/Apache), from Gallup, New Mexico, is also an artist with whom she has collaborated. Their first winter together in Browning, Montana, saw chill factors plunge to 87 degrees below zero. He toughed it out, but two years later they moved two hours south to Great Falls, where they’ve lived for 24

years. Their son, Paris, and daughter, Jade, are award-winning ledger artists and have worked and shown with their mother since they were smallchildren.Paris,acollegestudent,hasbeen showing since he was 5. When Jade was a baby she lay bundled on the kitchen table among beads

and leather while her mother worked.

Jackie Bread has won more than 90 awards for her

beadwork, most recently the prestigious Best of Show at the 2013 Santa Fe Indian Market. The award-winning bead artist never has inventory in stock — a nice problem to have. Always working toward the next major show, she says, “More is expected, now. You’ve really got to bring it.”

A vision of her history shines through as her work transports the viewer to a powerful sense of place and time. Jackie Larson Bread, a contemporary woman keeping tradition alive, is playing a large part in the revival and survival of Plains Indian art. “I tell my story,” she says. “It’s what I know.”

- Like all of her works, this floral purse tells its own story.

- A selection of necklace bags include hummingbird, buffalo and bear imagery, along with a man with a split-horn headdress.

- Bread’s remarkable portraits of Mountain Chief and Yellow Kidney, both Blackfeet, are seen on her beaded moccasins. The pipe bag, 6 x 24 inches, features Bull Bear. Both were completed in 2013.

- This 2006 horse cylinder case is 4.5 x 18 inches and features blue trade cloth with rawhide lining.

- She also beaded this stunning laptop sleeve.

- In a marvelous nod to the times, Bread beaded both sides of a lunch box.

- This 2011 otter bag features Blackfeet floral design on smoked buckskin.

- Bread’s 6-inch canteen bag features a Southern Cheyenne girl that Jackie knew.

- This beaded horse necklace bag is 3 x 4 inches.

- Memory Keeper, Bread’s portrait of Thunder — Jim Night Rider, won Best of Show at Indian Market in 2013.

No Comments