01 Aug Talking with the Clay

IN 1918 ONLY 83 PEOPLE SURVIVED AN INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC AT SAN ILDEFONSO PUEBLO, just 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Now, it is hard to imagine how isolated the pueblo was in those days — and how poor. With much of their land taken by neighboring Hispanic and Anglo people, with their fields troubled by drought and too few men to work them and with the tribe’s watershed losing its trees to logging, San Ildefonso people were in trouble. The other Tewa pueblos had similar problems.

Two talented people, Maria and Julian Martinez, were among the survivors of that epidemic. Maria and Julian had been making pottery to sell for 10 years. They started with polychrome in the style popular with San Ildefonso potters in the late 1800s, made for use in the pueblo and for the tourist market that came with the completion of the railroad to Santa Fe in 1880. Maria shaped and polished the pots; Julian gradually mastered the art of painting them.

Inspiration surrounded the couple. Great potters within their families were working in the pueblo. Archaeologists excavating nearby ruins (in what would become Bandelier National Monument) asked Maria to produce vessels styled after broken pots they had dug from the Ancestral Pueblo villages. And Julian spent years working at the Museum of New Mexico, where books and collections introduced him to pottery from all over the prehistoric Southwest.

Maria and Julian began to experiment, first with black pottery fired in manure-smothered blazes, as Santa Clara, Ohkay Owingeh and San Ildefonso potters had done for many years. One day in the winter of 1919-1920, Julian tried painting a design on one of Maria’s pots after she had polished it, using the clay slip she had used for polishing. A new kind of pottery came from that firing — matte black (where Julian had painted) on polished black (where Maria’s carefully rubbed slip still showed).

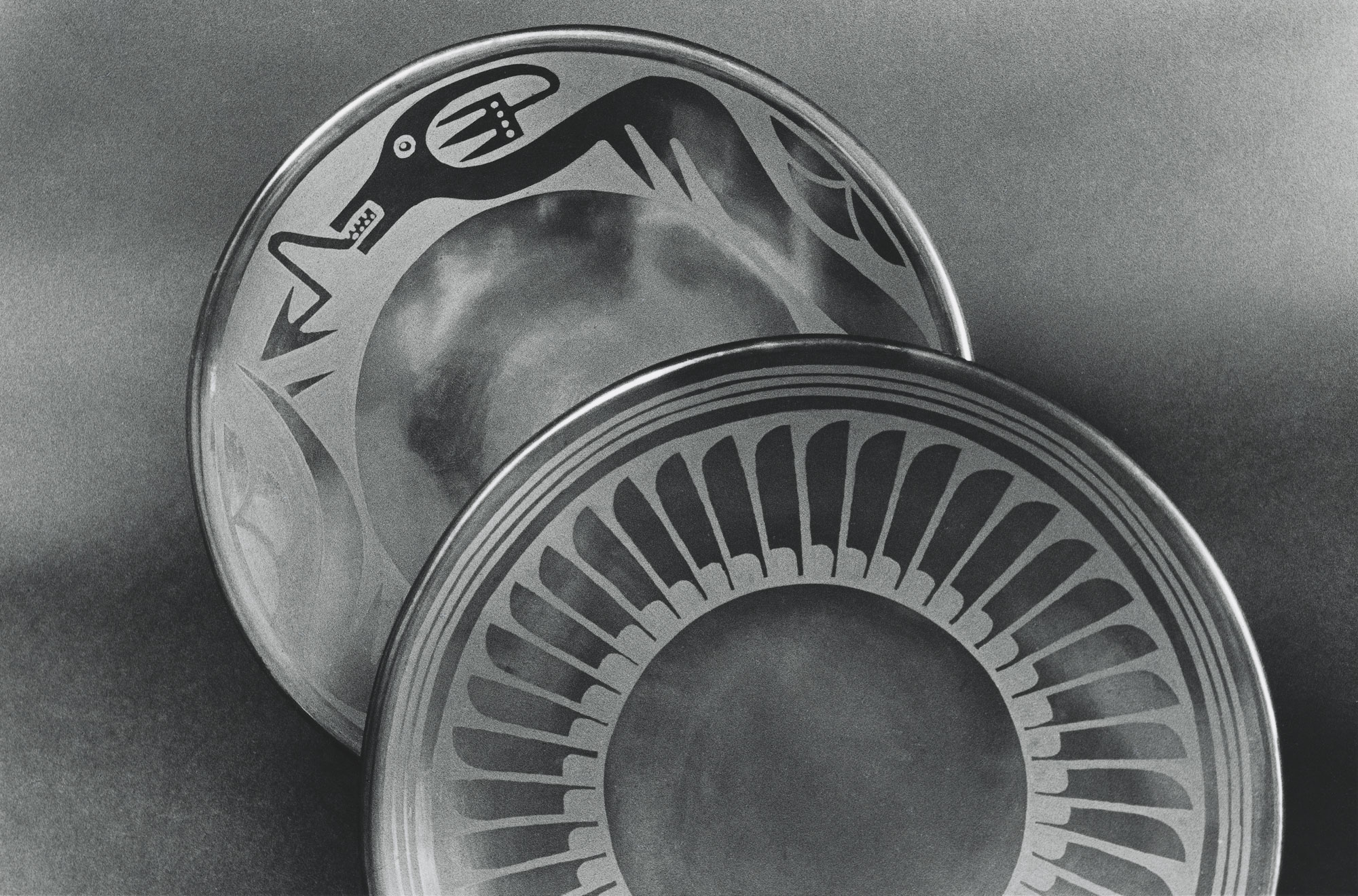

Julian’s invention and Maria’s incredible polish caught on immediately. San Ildefonso black-on-black pottery became so popular that by 1925 several families in the pueblo supported themselves with money from “two-black” pottery sales. With a slightly cooler firing, they sacrificed a bit of hardness but gained a jet-black finish deeper than the chocolaty black favored at Santa Clara.

Julian kept a notebook of ideas gathered from pots that caught his fancy. He revived ancient designs and transformed them to match his artistic vision: the old Mimbres radiating-feather pattern and the plumed water serpent (called avanyu in Tewa, drawn with feathers at San Ildefonso and horns at Santa Clara). Julian likened the water serpent to the leading edge of a flash flood pushing down an arroyo. When Maria spent their pottery money on a Model T, Julian even painted the new car with his hallmark matte-black designs.

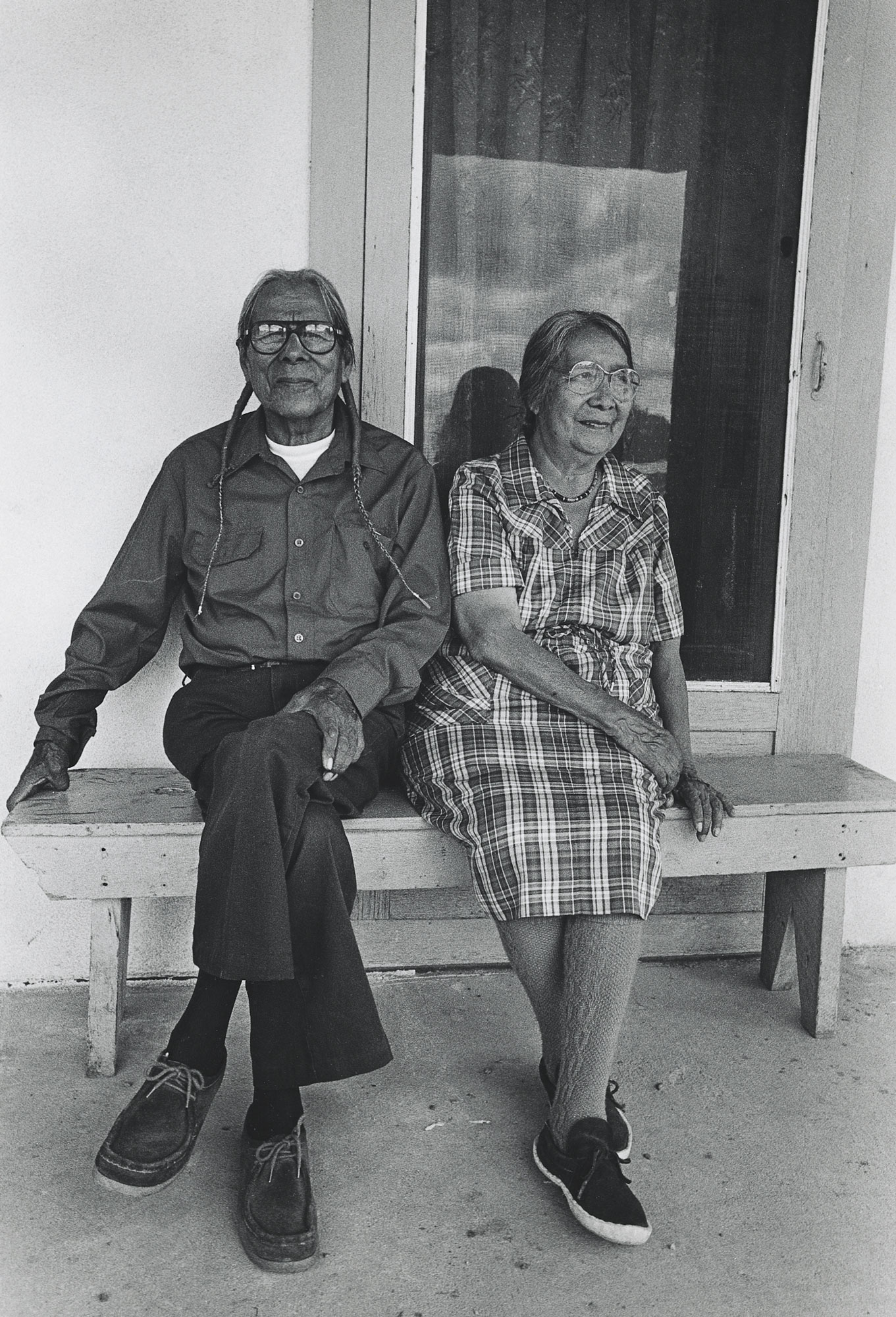

Julian’s creativity and Maria’s skill and determination combined to make Pueblo pottery more than useful. Working alongside other great early 20th-century potters from San Ildefonso, they transformed it into an individualized art and a profession. Julian died in 1943, but Maria continued making pottery until 1972. Her daughter-in-law, Santana, decorated Maria’s pots until 1956 when Maria’s son, Popovi Da, took over. Popovi died in 1971; Maria in 1980. Throughout these years, Maria’s youngest sister, Clara, specialized in polishing.

Maria was the first Pueblo potter to sign her work consistently, yet she always said that what mattered most was that it was San Ildefonso pottery, not that a particular woman made a particular pot. Later in life, she attempted to shift attention to other San Ildefonso potters — mentors and relations who made pottery just as innovative and beautiful — but the myth of “Maria, the Potter of San Ildefonso” had already taken over.

Maria’s real legacy survives in the rejuvenation of potterymaking at San Ildefonso and other pueblos and in the creation of a livelihood earned at home, where the old traditions can be nourished. Santana and Adam (Maria’s oldest son) made pottery in the style of Maria and Julian for decades. Now, a cohort of their daughters, granddaughters and great-grandsons, as well as an assortment of cousins, makes pottery.

With prolific enthusiasm, Marvin Martinez and his wife, Frances (from Santa Clara), carry on the Martinez tradition of black-on-black pottery. Marvin was raised by his grandparents, Adam and Santana, until he was 12; he traveled with them and danced to Adam’s drumming in many places far from the pueblo. He speaks of the elders with enormous respect and affection, especially Adam, who was “always teaching him.” While Marvin would be watching TV in the front room as a kid, Maria and Clara would be polishing pots in the back room. When he came back to “touching clay again” as a young adult, he remembered everything he had learned.

Marvin and Frances sell their work under the portal of the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe, especially in the spring.

Marvin loves to tell stories about people who discover his connection to Maria: “Their parents met Maria and Julian, met Santana and Adam. They inherited the pottery, and they have come to see where it came from. They have been told, ‘I don’t think you’ll find anybody from the family doing the traditional black-on-black.’ And so they are thrilled to find us, right where Maria and Julian were in the 1920s.”

Frances emphasizes, “We don’t say, first thing, ‘Yes, he is the great-grandson of Maria.’ We want the pottery to speak for itself. The most rewarding part is making long-lasting friendships. You welcome people to your house. You welcome people into your heart.”

Barbara Gonzales, one of Santana and Adam’s granddaughters … credits Maria with being the “major force behind getting clay recognized as an art form” and calls herself a clay artist instead of simply a potter: “As an artist, if you let yourself go, you will find yourself doing different things.”

In a small pueblo like San Ildefonso, many potters remain connected to Maria. Erik Fender could say, “Buy my pottery, because Maria was my great-aunt and Carmelita Dunlap was my grandmother.” But, like the other potters, he wants his pottery to stand on its own: “I talk with the clay in the building. Then, completed, the clay talks to the people. It says, ‘Take me home!’”

… The stories in Talking with the Clay now span seven generations and more than a century.

In the past 20 years [since the original edition of this book was published], much has changed. Confident young Pueblo potters bring sophisticated university training to their art, along with skills of the digital age. They push the physical limits of clay and the academic definitions of Indian art. More and more, the Pueblo potter stands alone as an individual rather than as, first and foremost, a community member. Each Pueblo artist must forge a personalized definition of identity and culture. Nothing is a given in a world where “Pueblo people have embraced self-determination in their personal life,” in potter William Pacheco’s words.

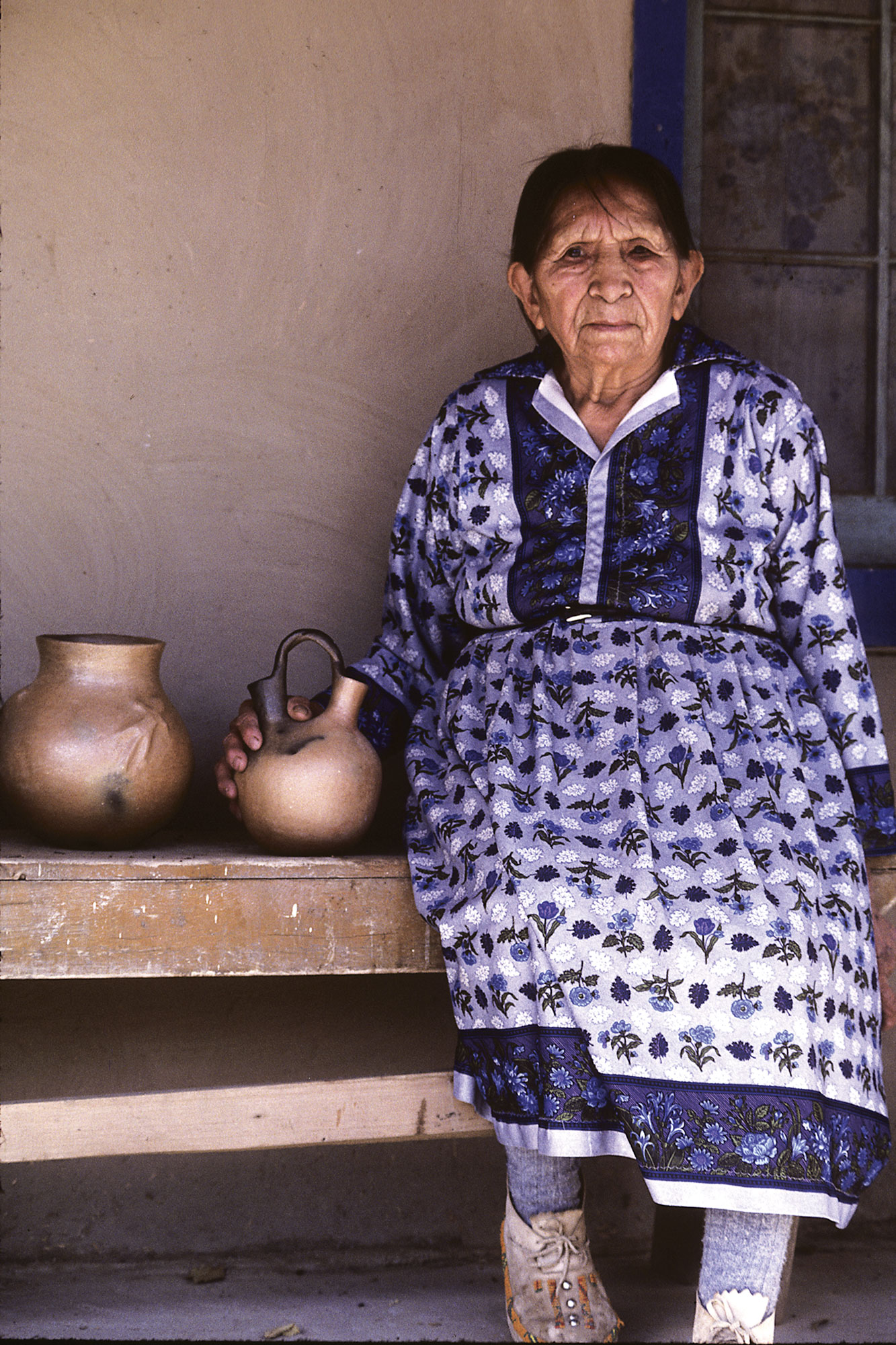

In the grandmothers’ generation, a Pueblo woman incorporated potterymaking as part of her cultural identity. On First Mesa at Hopi or at the pueblos of Santa Clara and San Ildefonso, nearly every woman learned to make pottery. In the final quarter of the 20th century, as the “dominant culture” created a market for Indian art, dealers and collectors favored the families with familiar names — descendants of the better-known matriarchs. For young members of these families, there were expectations to be met.

Today potterymaking is a choice, no longer a cultural fundamental. Only those Pueblo people who consciously make art from clay, whose primary joy comes from creating, become potters now. They may be men or women, from a heavily marketed family or not, young or old, reservation-based or city-based, dedicated to their grandmother’s techniques or open to kilns and all the tools available today. These are the new Pueblo potters: “transmitters,” as Santa Clara sculptor Roxanne Swentzell puts it, individuals, artists — grumpy about the narrow categories used by judges at markets and Indian fairs and eager to defy these constraints, yet proud of their heritage. Caroline Carpio gleefully entered her first bronze casting of one of her Isleta pots at the Heard Museum Indian Fair: “Does pottery always have to be clay? I wanted to test the meaning.”

A few become celebrity potters. They create intricate Web sites and sell their pots for tens of thousands of dollars. The communal society of the Pueblos is shifting, allowing artists more comfort in that spotlight prized by the dominant culture, escalating competition in the cooperative Pueblo world. Each artist must come to terms with the dilemma articulated by Caroline Carpio: “I like being different, but I don’t like standing out in a crowd.”

Suburban Indians still return to their pueblos to dance in plazas on feast days, to listen to elders, to stay in touch with ever-extending families. They nourish their connection to traditional culture — at the risk of becoming, as one potter fears, “commuters playing Indian on the weekend.” For those who live in the pueblos, creativity depends on distancing themselves from the looping electronic arpeggios and tinkle of slot machines pouring from the nearby tribal casino.

Potters look for ways to tell these stories — more complicated stories than the previous generations sought to tell. Figurative potters sculpt 21st-century stories in clay. The designs they draw and carve on their bowls embrace irony and politics, tragedy and whimsy. The line of stories and teachings handed down through the generations by the grandmothers and aunties still exists. But it follows a more wandering path, and potters worry that their children may not learn the full power of that ancestral lineage.

For “tradition” to be anything other than stagnant, it must embrace change. In truth, the time to set aside the concept may have come, for it seems to confuse as much as it communicates. Virgil Ortiz bridles at the notion that tradition means doing only what your grandmother did: “What about your grandmother’s grandmother?” Diego Romero says, “The matriarchs of traditional pottery were very contemporary for their time.”

Tammy Garcia, another of today’s innovative potters, “still loves the word.” To her, tradition “holds a lot of information. In the broader sense, it means change, adaptability. It also means the continuing ability to do something better than before.” Max Early, at Laguna, says that tradition “illuminates through the potter’s soul.” Art historian Ralph T. Coe comes close to expressing the power of tradition when he describes it as “something Indians step into in order to be themselves.”

This past generation has also transformed the marketplace. As potters create finer and finer pieces, prices rise. Contemporary Pueblo pottery turns up in Sotheby’s auctions, and the bidding is lively. As the value of pottery increases — and as collectors insist more on “perfection” — more and more potters use electric kilns to reduce the risk of loss in firing. With greater control, more pots survive. With greater production, collectors can be far more selective.

Collectors have a choice of buying pieces made by “the copiers, the refiners, or the innovators,” as Santa Fe gallery owner Robert Nichols puts it. The copiers make pots exactly as their families have made them for decades, and these lovely, recognizable pieces remain most affordable. The refiners take technique to the limit, creating extraordinary “high-craft” pieces still in keeping with familiar styles of their pueblos. The innovators create individualistic and unpredictable art. Their explorations lead to dead ends, to interesting phases they pass through and then abandon, and, finally, to successful experiments — and the future of Pueblo pottery.

Tammy Garcia — who knows that she is one of the potters whose work “pushes the market” — saw a crossover point: “Twenty years ago, the wholesalers picked the safe pieces, and only a few picked the unusual pieces. A transition began in 1986, when the unusual pieces began to take over. It took five years.” Those high-end pieces have tugged prices upward for the bread-and-butter pottery — but fewer reputable galleries stock a wide range of pieces. The newcomer has to search harder for nicely made, affordable pots and dependable information.

The World Wide Web makes educating yourself easier. Search for Web sites rich with information, and avoid those that feature only a few misidentified pots with half-truthful captions. Coordinate your trip to the Southwest with a major Indian art show, fair or feast day. When you visit Pueblo country, ask questions in museum shops. When you find knowledgeable dealers and museum docents, keep them talking for as long as you can.

The joy of talking with the potters themselves has not diminished. Look for “Potteries for Sale” signs in the windows at First Mesa, Taos, Acoma. Ask around for the homes of potters whose work you love. Knock on doors. Find excuses to begin conversations. Delight in directions like “Turn where the store that burned down used to be.” Potters still prefer to sell directly to you, and not just because they make a higher percentage that way. They would rather tell their stories and build relationships than simply pocket the money paid by a wholesaler. Listen as Marvin and Frances Martinez hold forth from their perch “on the other side of the cloth,” surrounded by their San Ildefonso pottery under the portal at Santa Fe’s Palace of the Governors. Frances says, “You get people who don’t know the faintest idea about pottery. They leave being educated. Even if they don’t buy a pot, they walk away with a gift in their heart. It’s a lot of history. It’s a lot of art.”

The word tradition and its physical expression in pottery capture the Pueblo people’s fierce sense of community and each potter’s new ability to face outward and stride unaccompanied into the 21st century. The two forces grind together like continental plates, with all the attendant tremors, subductions and accretions. With poise, Pueblo potters negotiate a graceful balancing act along the zone of contact, guided by Tammy Garcia’s “adaptability” — living with serenity among the shower of sparks generated by the tensions between old and new.

- Bessie Namoki shaping, polishing and painting a small Hopi pot, 1984.

- San Ildefonso plates by Adam and Santana Martinez, 1971.

- Carved red pot by Tammy Garcia, 1996. (Blue Rain Gallery collection)

- Making Herself , Clay sculpture, by Roxanne Swentzell, Santa Clara, 2006. Collection of Georgia Loloma. (Roxanne Swentzell Tower Gallery, Poeh Center)

- The late Adam and Santana Martinez, San Ildefonso, 1985.

- Isleta jar with corn appliqué by Caroline Carpio, 2006.

- Virginia Romero, Taos pottery elder, with her micaceous pots, 1985.

No Comments