12 Sep Teton Teater

THIS NOVEMBER, THE ART MUSEUM OF EASTERN IDAHO opens an exhibit featuring the works of artist Archie Boyd Teater. Entitled Visual Narratives of the American West, it references Teater’s home and studio in the Hagerman Valley, the only project designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in Idaho.

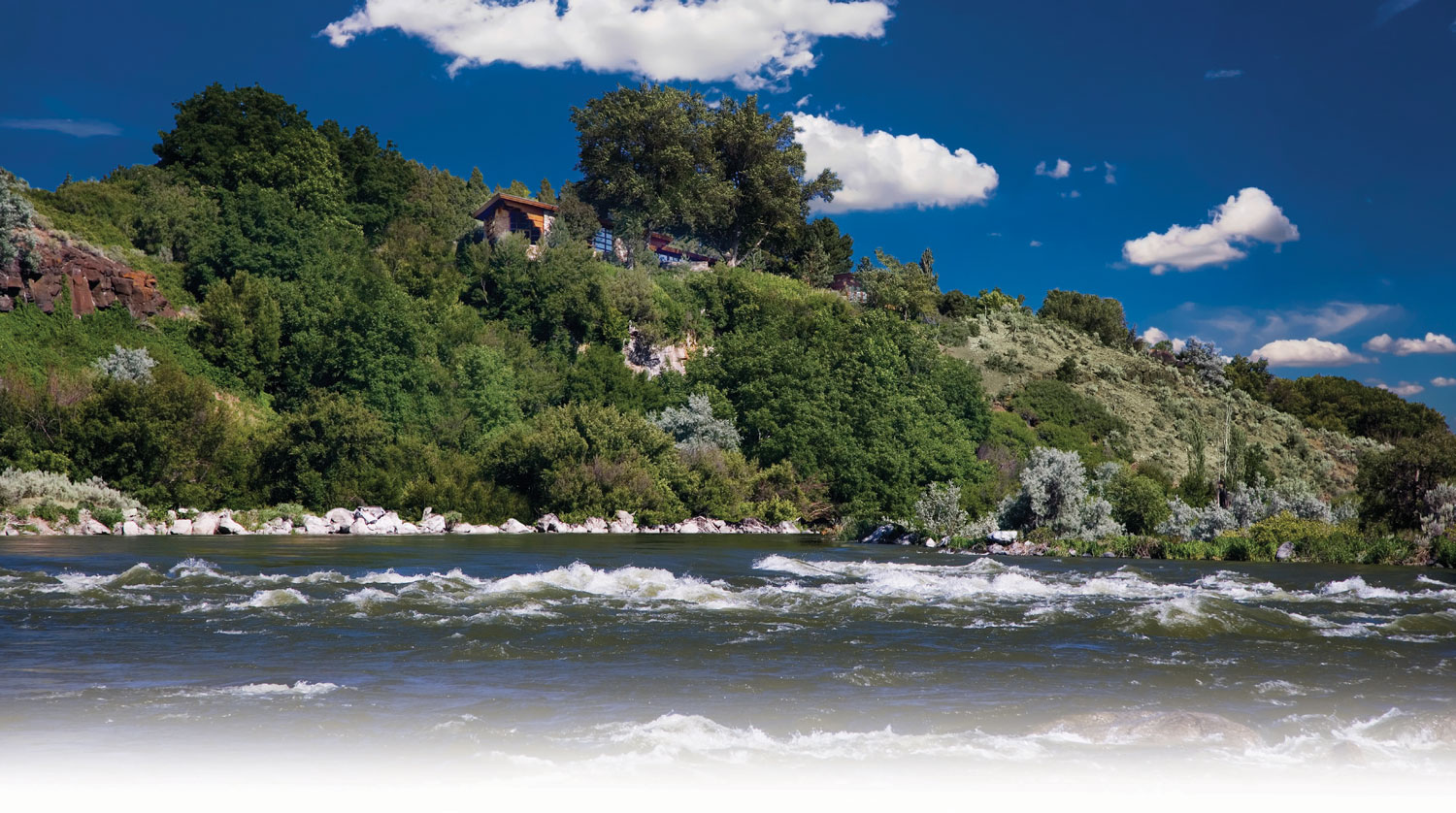

From across the Snake River, the studio’s position on the steep cliff is evident. Archie Teater fished for sturgeon in the Snake River and sold his catch to mining camps. He also ran trap lines here to buy food and paint in his early years.

At the time of his death, Teater [1901–1978] was one of the best-known Western landscape painters in the country. He was featured in such magazines as Look, Flair, Ideals, Better Homes and Gardens, and others that were the metrics of stardom. He had a solo exhibition in New York City, his works hung in the Metropolitan Museum of Art among others, and significant private collectors owned his paintings.

Archie Teater’s easel, loaned by the Hagerman Valley Historical Society, is located where a historical photo shows he painted. The paintbox on the table is also Teater’s and one he took out for plein- air work. Teater’s paintings of the Guggenheim Museum (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright) and the dragon were also borrowed from the Hagerman Valley Historical Society, which is seeking to build a larger exhibit space to make Teater’s work better known.

Miyai Abe Griggs, director of the Idaho Falls museum, draws connections between Teater’s story and his artwork. “His paintings of early Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and Idaho depict living in the early American West as a primitive struggle for survival. His is a fascinating story: poor, gritty, and born into a family that did not value art. He pulled himself up through years of struggle to support himself through his artwork, to travel the world, and to commission a studio from Frank Lloyd Wright, the most famous architect at the time.”

Lester D. Taylor, author of The Life and Art of Archie Boyd Teater and a collector of the artist’s paintings, says that before Teater was 20, he worked in logging camps, trapped, fished, prospected, panned for gold, and was a muleskinner. There are stories of him selling his guitar to buy paint and selling paintings for rations of food and firewood to survive winter.

“Always, he painted. He was very prolific, usually painting a canvas a day, but sometimes even one or two more,” notes Taylor. “We know of approximately 4,000 paintings, but there may be as many as double that number. His style was simply his own. He painted mostly plein air, from experience, and what he saw. He had a sense of humor and could tell a story in a painting.”

Opposite the windows overlooking the river is an office area with a desk designed by Wright and commissioned by the current homeowner, Henry Whiting II. The lamp was also designed for the studio and home, and built by Whiting. The wood-fired ceramic on the desk is by Shiro Tsujimura, who also created a number of the tea bowls on the shelves. The bookshelf on the right is the partition separating the sleeping area from the primary living spaces.

Despite financial struggles, Teater pursued art training. He spent two winters at the Portland Art Museum during his 20s, and later, he spent eight winters, from 1935 to 1956 respectively, at the Arts Students League in New York City.

The Wright-designed dining set enjoys a commanding view of the Snake River.

In the summer of 1928, he traveled to Jackson Hole for the first time. The visit initiated a lifelong love of that landscape, and he spent nearly every summer thereafter in Wyoming. He began the season working for the U.S. Forest Service, constructing trails in Grand Teton National Park until he had enough money to focus on painting. Then, Teater set up a camp and outdoor studio at Jenny Lake to sell his work.

In 1941, at the age of 40, he married his wife Patricia. She took over sales and marketing, leading to years of greater prosperity. By the mid-1940s, Teater became known as “Teton Teater.” In 1945, the pair opened a cabin-like studio in Jackson Hole, and operated it in the summers until Teater’s death in 1978.

Looking toward the front entrance from the area where Teater painted, is the living room with furniture designed by Wright, including the ladder-backed dining chairs and built-in table. The partitioned sleeping area is to the left of the large stone fireplace, another of Wright’s identifying design features. Behind the fireplace to the right is the “work area,” Wright’s name for the kitchen. Note the diagonal design of the ceiling, another Wright hallmark.

Through a series of letters that referenced her roots in Oak Park, Illinois, and personal connections with the famed architect’s family, Patricia convinced Wright to design a studio on the couple’s 2-acre parcel in 1953. Located on a basalt cliff in the Hagerman Valley near Bliss, Idaho, it was an area where Teater had lived off and on during both his childhood and adult years. The site offers 180-degree views of the Owyhee Desert and looks down to the Snake River where the great Bonneville flood dramatically scoured a mile-wide river valley with soaring 500-foot cliffs. The view stretches to the Trinity Mountains 60 miles to the north.

The Teaters bought the 2-acre Hagerman Valley parcel on top of the bluff overlooking the Snake River in 1949. Teater had previously lived in the area in a rock dugout and in a stone hut bought from bootleggers.

From the late 1950s, the couple lived and worked at the studio during both the spring and fall seasons. Summers were spent in Jackson Hole, and during winters they traveled the world. They visited more than 115 countries, and while traveling, Teater continued painting at his vigorous pace, producing what is termed the International Collection.

In addition to being the only building designed by Wright in Idaho, “Teater’s Knoll” is also the only art studio he designed, says Henry Whiting II, a landscape architect and architectural writer who’s studied Wright’s work. Whiting bought Teater’s Knoll following Patricia’s death in 1981, and he has painstakingly restored and maintained it since. His book, At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio, documents the history of the home and its restoration.

Cherokee red concrete continues from the interior to the terrace. The glass doors, overhangs, and continuation of materials all serve to unite the inside and outside, a feature common to Wright’s architecture.

Whiting calls the studio Wright’s most open and undifferentiated space. “Its simple humbleness exhibits total mastery of his craft,” he says. The studio is essentially a one-room building constructed of Oakley stone, wood, and glass. The only interior walls enclose the bathroom and kitchen workspace, and a partition separates the sleeping area. The roof rises to its highest point above the studio terrace, and the windows slope to parallel the roof plane. Teater painted in the natural northern light at the tall prow of the studio.

Patricia’s approach to solitary marketing and selling her husband’s paintings brought great success during the artist’s lifetime. She willed nonprofit groups Teater’s remaining paintings, but they could not maintain the momentum needed to keep his art in the public eye. Without a major gallery and active representatives to carry on, Teater sadly fell into near obscurity.

The prow of the home stretches skyward to represent inspiration while remaining anchored to the earth. Wright experimented with this form in the 1950s in a number of projects, including the Unitarian Church in Madison, Wisconsin.

The Art Museum of Eastern Idaho presents his work in three gallery spaces with the show running November 14 through February 8, 2020. According to Griggs, one gallery will focus on Idaho history, the second on the International Collection, and the third on paintings that Teater created for himself, not necessarily for sale, embued with more whimsy and fantasy.

“It’s important for Archie to be known again and it’s a big step,” says Lester Taylor, whose collection of Teater paintings will also appear in the exhibit.

No Comments