24 Jul The Neutra Legacy

RICHARD NEUTRA HAD A REPUTATION FOR DROPPING IN ON THE HOUSES HE'D DESIGNED. In 1960, when the Topper family moved into the Lovell Health House with four boys, a girl, dogs and toys, he took to dropping by nearly daily to inquire plaintively, “Oh! Why don’t you sell the place?” Completed in 1929, the Lovell Health House was the spectacular hillside dwelling that had catapulted Neutra into the forefront of Modern architects. But the house survived the rough-and-tumble of children, despite the architect’s worst fears, Betty Topper said. More than 50 years later, she still lives in the home with one of her sons.

“We called him the crazy man,” a now middle-aged Ken Topper explained last April during celebrations for the 85th anniversary of the Neutra practice. “He looked like Albert Einstein.” With flowing grey hair, piercing blue eyes, an Austrian accent and compelling personality, Richard Neutra made an impression wherever he went.

A 1949 cover story in Time magazine described Richard Neutra as “one of the world’s half-dozen top architects.” The Viennese-born modern architect came to Los Angeles in the 1920s, and his design philosophy embraced the optimism, sense of limitlessness and vibrant outdoor lives of southern Californians. Neutra believed homes should be designed for the well being of their occupants, and he gave his potential clients detailed questionnaires to fill out, sometimes requesting that they compose a diary of their activities. At heart, he believed that good design could change people’s lives for the better.

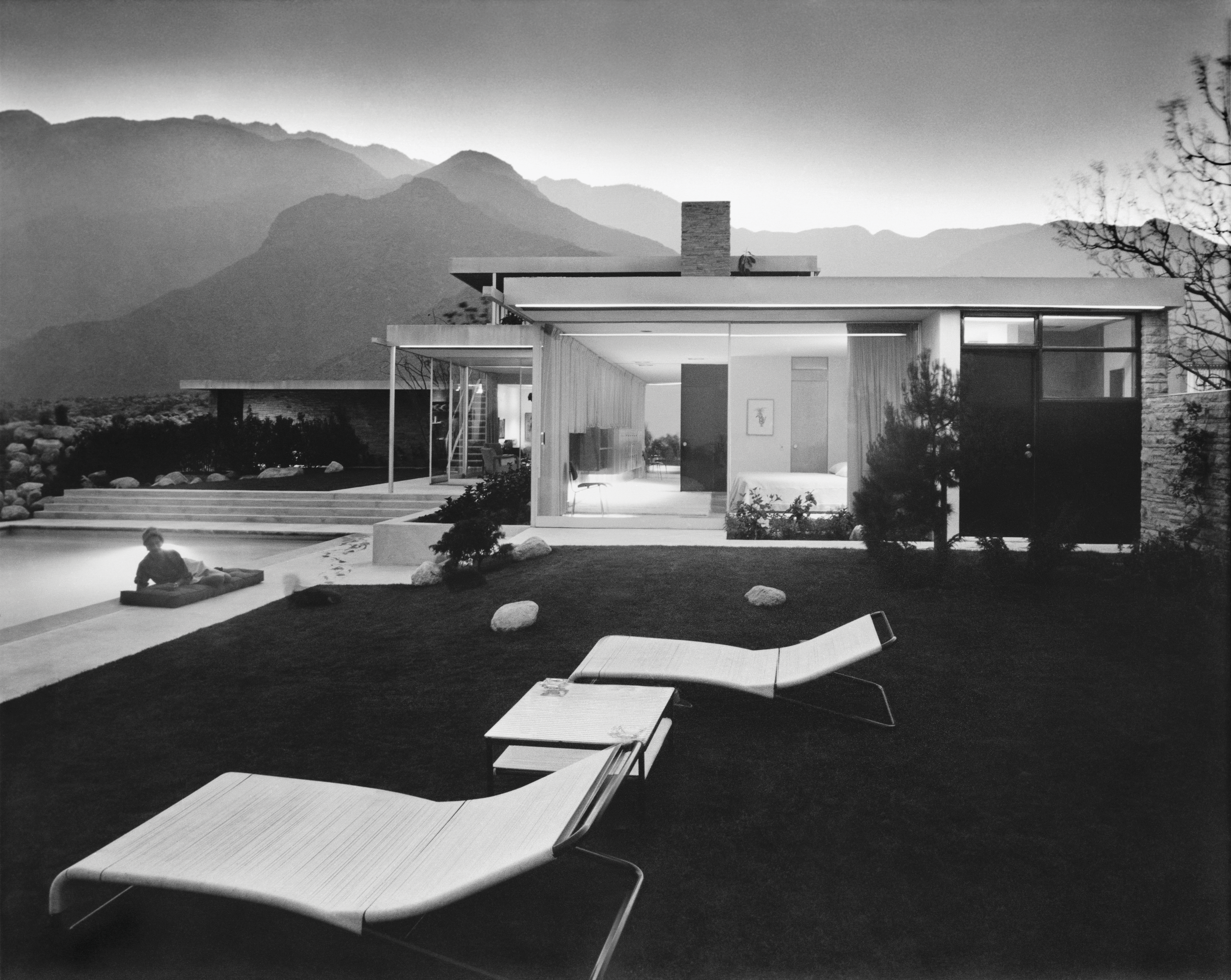

Neutra houses were horizontal post-and-beam constructions with floors layered atop one another. Walls of windows erased the division between inside and outside. Patios, decks and water features completed the simultaneous sense of oneness with nature and serene privacy. Mirrors and built-in furniture created the illusion that spaces were much larger than they were. To support the immense expanses of windows, Neutra designed some of the first houses in the United States constructed with steel frames. Though he embraced the austerity and functionality of the International style, his signature included wide overhangs and the warmth of wood, stucco and stone features.

Among his most famous homes are the Lovell House and the Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs (which he designed for the same Pennsylvania family that commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece, Falling Water.) A home he built for film director Josef Von Sternberg (which was later occupied by writer Ayn Rand, and which is now destroyed) was surrounded by a moat.

Neutra lived and worked in the VDL House across the street from the Silver Lake reservoir. It was named for Dutch industrialist C.H. Van der Leeuw, who’d been so horrified to learn that the famous Modern architect lived in a small rented apartment that he funded the building of a studio/home, which was completed in 1932. It burned in 1963, destroying a shattering amount of Neutra’s records, renderings and writing. It was rebuilt over a period of three years by Dion Neutra, Richard’s son, but his father lived only another four years after it was completed. Dione Neutra, Richard’s widow, lived there 20 years before entrusting its care to Cal Poly Pomona, which keeps VDL open for viewing.

Since his father’s death in 1970, Dion has carried on the practice, designing some significant buildings himself that illustrate the Neutra philosophy. Enlisted into drafting at the age of 11, Dion remains a passionate defender of his larger-than-life father’s legacy. He speaks of him warmly and after continuing the architecture practice alone for four decades, at 85, Dion Neutra’s main preoccupations are preserving the remaining houses and public buildings in an effort to keep the Neutra philosophy alive.

Dion joined the firm in 1950 after graduating from USC School of Architecture (after various detours, including World War II) and right after his father’s first heart attack. Despite his many accomplishments (among them, the Huntington Beach central library and the Scheimer house), his reputation has been overshadowed by his father’s, and he can be prickly about getting the recognition he’s due. Still, he feels their relationship has been misunderstood. It was, he says, far better than it’s been portrayed in, for example, Thomas S. Hines’s Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture.

In fact, Dion says, father and son had a deep meeting of minds, and he has carried on his father’s philosophy of design (which was first realized in the Lovell House) as a way to enhance the health of the user. “That became the watch-word of the practice,” Dion says, pointing to the many innovations he created in the Huntington Beach Library that increased the user’s experience, from water features that allowed people to speak at normal volume to variations in the interior design that were intellectually stimulating.

“In essence, the building is a culmination of the thinking that led up to it,” he says. “That’s what the Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design is about: to carry on research into those directions; to think about the interaction of the user and the environment.”

In spite of the resurgence of enthusiasm for Modern architecture that gained momentum in the 1990s, many of the Neutra firm’s creations have been allowed to deteriorate, been demolished, or are in danger of being demolished. The 85th anniversary of the firm’s founding, while a celebration of the enduring beauty of the designs, was also a dirge for buildings in jeopardy, like the Los Angeles Hall of Records or the Cyclorama building at the Gettysburg Battlefield, which was among Richard Neutra’s favorite public buildings. The building, dedicated in 1962, is shuttered and the National Park Service is debating between demolishing it, moving it to another site, or (a long shot) restoring it where it is. Dion Neutra has carried on a quixotic quest to save the building, which he envisions as a cultural center dedicated to Abraham Lincoln, and wonders how to contact President Obama.

“He can pardon a turkey,” he says. “Why can’t he pardon a monument?”

The Kaufmann Desert House, finished in 1946 and made famous by a Julius Schulman photograph, had over the years been rendered nearly unrecognizable by a series of “improvements.” Bought by Beth and Brent Harris, the home was meticulously restored between 1993-1996. But they are the rare couple with the money, the enthusiasm and the dedication to restore an architectural work of art to its original state.

In 2002, another Neutra desert house was purchased and summarily demolished. Another Neutra home was sold for $1 by a new owner who wanted to demolish. Split in half for the move, the home was moved from Beverly Hills to an area near downtown that’s primarily Victorian houses. Half was moved one night and made the news, so that the city of Beverly Hills took note and said Sunset Boulevard couldn’t stand the weight of the other half being moved. After much dickering they allowed the other half to be moved, but by then the recession had taken hold, and the woman who’d bought the house couldn’t afford to carry on. So the two halves sit on the lot on blocks, decaying, vulnerable to weather and possible earthquake.

One problem is that in an age, and in a country, where bigger is considered better, Neutra’s houses can seem cramped. The bathrooms and kitchens are minute by today’s standards. The elegantly pared-down houses are works of art on their own; they don’t tolerate collections of knick knacks.

“Simple is best. I think of it as a ship,” Janice Furman, who’s lived in her Neutra house since 1971, said at an anniversary gathering for Neutra homeowners. Even though the Neutra was larger than her previous home, she had to shed furniture. “I enjoy it maybe even more as each day goes on.” But she, like other owners who spoke, said that a Neutra is something one learns to live in.

Architect Al Rae remembers the night in 1963 when the VDL burned down. He was still an architectural student at USC, and he and his wife, Susan Welch Rae, rented one of the small apartments behind the office building Neutra had built on Glendale Boulevard in the early ’50s, steps away from the VDL. By then Neutra’s heart condition had worsened, and he sometimes received visitors while sitting in bed dressed in pajamas made more formal by the addition of a tie. This might have lent a less charismatic man the appearance of vulnerability, but Rae remembers it as making Neutra seem all the more intimidating.

Among Rae’s many volunteer efforts for Neutra was the job of chauffeur. He and Susan dressed up one day to drive Neutra to a meeting at UC Riverside. The meeting went on — people were mesmerized by Neutra — and they got a late start back to Los Angeles. Suddenly Neutra suggested they should see some of his houses, and they began stopping to knock on doors. For people who weren’t the original owners, Neutra held up a photo of himself on the cover of a German magazine. The last visit was in the small hours of the morning to a bewildered woman roused from her sleep to show her house to this little band of strangers.

Today Dion Neutra has a printout of all the firm’s houses and buildings. But many have changed hands in recent years, and there’s no way of knowing who their present owners are, nor what their fate will be. A Neutra on two acres in Beverly Hills recently was offered for sale at more than $13 million. But there’s no guarantee the buyers won’t tear it down and erect yet another of what Dion Neutra calls “McMansions.” Neutra hopes that owners of landmark houses, like Betty Topper of the Lovell Health House, will draw up papers to make their sale conditional on preservation.

In the meantime, to track down Neutra creations, he will have to once again follow in his father’s footsteps, and knock on doors.

- Lovell House, Los Angeles, California, Julius Shulman, Gelatin silver, circa 1950-1967 | © J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute

No Comments