04 Aug The Phyllis Shafer Experience

I USED TO THINK IF I SAW ONE MORE SOUTHWESTERN LANDSCAPE, I’d go crazy. Then I came across my first Phyllis Shafer painting.

Landscape painters strive to create a mood through a sense of place. Works can conjure awe, like viewing a majestic Albert Bierstadt painting of the Yosemite Valley or a Thomas Moran romantic sunset over the Hudson River. By contrast, Neil Welliver’s impressions of Maine offer moments of quiet contemplation. What unites all of the great landscape artists is how they awaken long-dormant feelings in viewers. Phyllis Shafer’s work makes me want to call my travel agent. In today’s high-tech, social media-infatuated world, landscape painting seems antiquated, almost out of touch with the times. That’s what makes Shafer’s work so special. Most contemporary landscapes feel apologetic. It’s as if the artist is saying, “I know I shouldn’t being doing this, but I just can’t help myself.” With a fearless interpretation of the great outdoors, Shafer takes the opposite tack. Though highly personal, her imagery is universal enough to connect with the viewer.

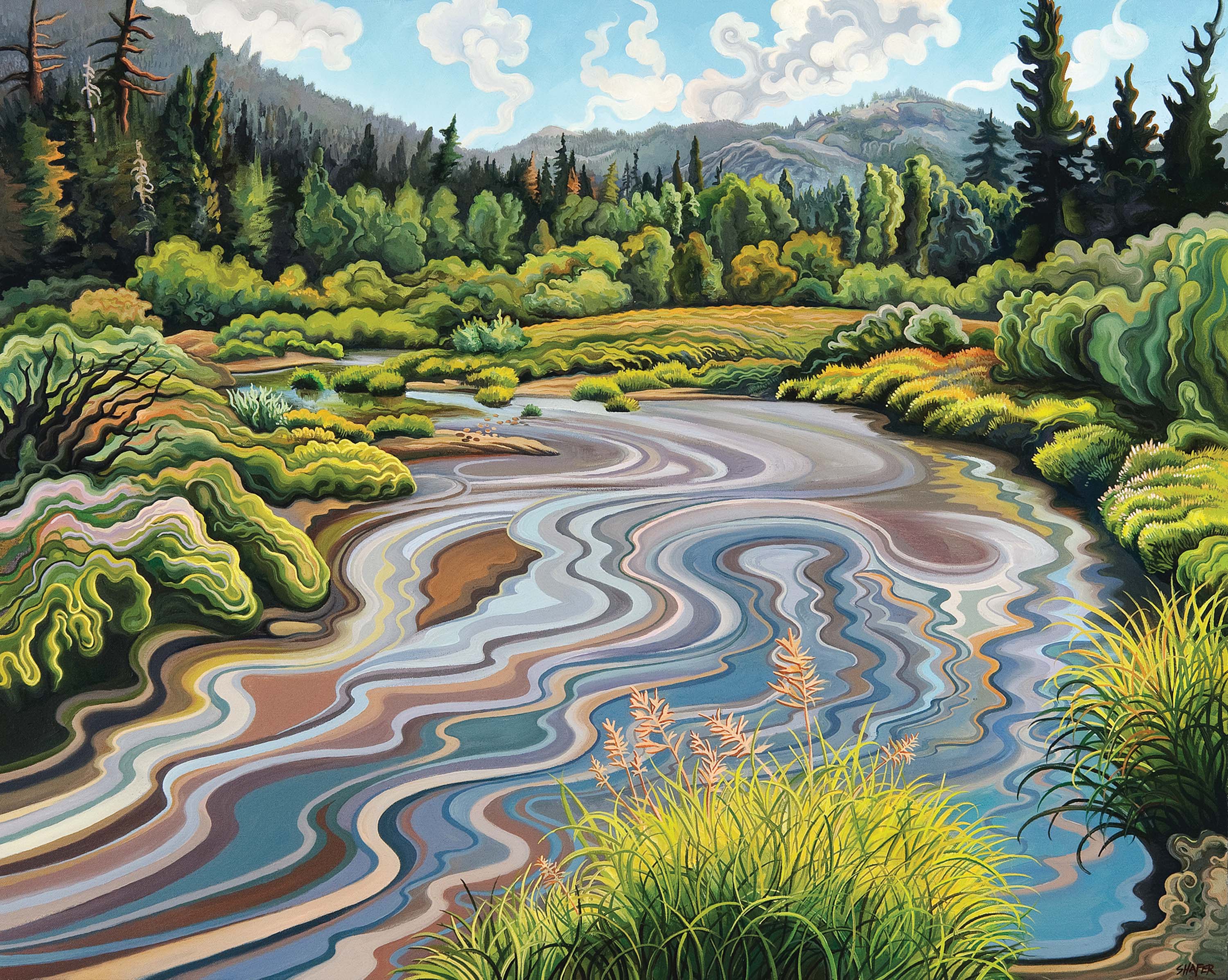

Shafer funnels her paintings through a filter that distorts and bends the scenery to reflect how she experiences it. Like the hallucinatory water-

colors of Charles Burchfield, Shafer sends out undulating waves of color, which quickly imbed themselves in the viewer’s psyche. Commenting on her work’s affinities to Burchfield, Shafer admits, “I love his fanciful response to nature — you can hear the crickets and raindrops. For me, his paintings are about sound.”

“I feel a strong connection to the American Modernist painters like Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove and the lesser-known Canadian artist Emily Carr. But the greatest influence on my work has been plein air painting,” she explains.

“Through direct observation, you understand the essence of a place. I begin all of my pictures outdoors and complete them in the studio. A finished work is concerned with how I feel about a landscape more than how it looks.”

My own favorite Shafers are the Southwestern landscapes, such as Prickly Pear Evening, which reads like a compendium of Sonoran desert flora: saguaros, creosote trees, chollas, prickly pear cacti and ocotillo. These exotic succulents create a bond with anyone who has ever walked the land surrounding Tucson — and often with those who haven’t. It’s a little like having a déjà vu moment; you know you’ve been there before, whether in your dreams or in person.

Shafer’s body of work can be split between realism and those paintings that cross over into stylized abstraction. Her most realistic pictures depict scenery she viewed for the very first time. When a spot proves particularly productive, she’ll return and continue to mine it. With these repeated efforts, the imagery begins to weave back and forth between fantasy and reality. A good example is Upper Truckee Gambol, a panorama literally from the artist’s own backyard. The stream’s expanding bands of color have a psychedelic quality. Yet, the marbleized water is counterbalanced by a tightly rendered forest of conifers. It’s this contrast between traditional land-scape painting and cutting-edge contemporary art that gives the work its creative tension.

Shafer has a mainstream art background. She did her undergraduate work at the State University of New York and received her master of fine arts degree from the University of California at Berkeley, where she studied under Bay Area painters Christopher Brown and Joan Brown (no relation). Upon graduation, Shafer was determined to support herself by teaching. She bounced around a bit, eventually finding a home at Lake Tahoe Community College. She currently teaches full-time and serves as the department chairwoman, yet somehow carves out enough space in her hectic schedule to paint.

Shafer has the enviable track record of selling everything she produces, and is effusive in her praise of Turkey Stremmel, her primary dealer, at the Stremmel Gallery in Reno. “She’s been a great influence, liberating me to allow the work to go where it goes. Turkey made it clear to me that she’ll stick with it.” That’s a bigger deal than it sounds. In these market-obsessed times, many dealers pressure their most established artists to keep producing what’s been selling, rather than take risks that allow for growth. A long-term commitment from Stremmel has allowed Shafer to continue to expand her scope.

For Stremmel, that commitment and growth is rewarding for artist and viewer alike. “When you look at her paintings, you feel like you can walk through them. They take you on a mysterious journey. Every time you stand in front of one, you see something new.” That, of course, is the key to art that survives the test of time.

As her career takes her across the country, and across the ocean, Shafer’s work is continuing to evolve. “In some ways, I feel like I’m about to enter a transitional phase. Next year, I’ll be taking a short sabbatical from teaching and plan to travel to Italy and paint. I also applied for an artist-in-residency program at Ucross in Wyoming. You may not know this, but our national parks also have residency programs. I’m looking into one at Joshua Tree National Park.”

But will her travels bring wildlife or people into her land-scapes? “I’m open to including other ‘participants’ in the natural world. It just can’t feel staged — it has to feel right. Basically, when I get out in nature I want to get away from people. The torqued perspective in my paintings evolved because I see things that way. It’s largely due to being alone with the natural world.”

In 2014, Phyllis Shafer will be honored with a mid-career retrospective at the Nevada Museum of Art. According to the curator of the exhibition, Ann Wolfe, “Shafer’s paintings capture the sublimely beautiful spirit of the Western land-scape, reflecting a broad range of art, historical influences and inspirations.” It will be a substantial exhibition that will occupy a 6,500-square-foot gallery. The show is designed to highlight the evolution of the work and will include a number of little-seen early paintings. Wolfe described these canvases as nature-based, but “inward looking.”

With an upcoming museum show, solid gallery representation and a long list of collectors waiting for the next painting, Phyllis Shafer appears to have achieved everything an artist can want. But she doesn’t plan to stand pat; there’s still a hunger to gradually push the work in new directions.

Shafer’s art reminds me of a fine bottle of red wine. The first sip is always good, but as the wine opens up, the next few tastes grow richer and deeper. I’ve enjoyed Shafer’s work to date, but I have a feeling each new painting represents another sip of a great wine, with many more future pleasures remaining in the bottle.

- “Sulpher Buckwheat Morning” | Oil on Panel | 20 x 16 inches

- “Ruby Mountain Cirque” | Oil on Canvas | 22 x 46 inches

- “Lamoille Canyon Beaver Pond” | Oil on Canvas | 22 x 25 inches

- “Upper Truckee Gambol” | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 30 inches

No Comments