24 Jul The Return of Bill Schenck

On the palette of Bill Schenck you will find the colors of Maynard Dixon, plenty of Sergio Leone, a touch of Andy Warhol, a blend of Anthony Mann and John Ford, the shadows of Ansel Adams, strokes of Ed Mell and Ingmar Bergman — and all of himself.

Oil painter, photographer, Western film buff/critic/historian and cowboy, Schenck became a leader in the Contemporary Western (or Southwestern Pop) movement in the early 1970s, known primarily for taking black-and-white stills from Western movies and re-imagining them with brilliant colors. Then, like a lot of Western movie stars, his career began to fade.

Rather than ride off into the sunset like the quintessential Western film hero, Schenck is back at work in his Santa Fe, New Mexico studio, bringing a new look to his art while maintaining that sharp Schenck edge. That is, when he’s not competing in some ranch-sorting event on his horse, Badger. He won the 2009 world championship in the master’s division in Ponca City, Oklahoma, and took the New Mexico master’s title last year.

“The painting’s interfering with the sorting,” he quips, although he admits it takes a lot of Aleve and plenty of teeth grinding to get through a sorting event, a timed competition in which riders work to cut correct cattle out of a herd and drive them into a pen.

Painting’s a tad easier, and he’s winning at that again, too.

A retrospective, Bill Schenck: The Serigraphs, began a five-month run in February at the Tucson Museum of Art; he was scheduled to headline a three-man show, Earth and Sky, with Logan Maxwell Hagege and Glenn Dean, in June, at Altamira Fine Art in Jackson, Wyoming; newly signed to Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe, an exhibition of his new works opens July 29; and his work is included in Western Horizons: Landscapes from the Contemporary Realism Collection, which runs through October 23 at the Denver Art Museum.

All this from an artist whose paintings can already be found in museums and private and corporate collections across the world.

“Bill Schenck’s work has long been called Contemporary Southwest or sometimes even Southwestern Pop,” says Julie Sasse, chief curator and curator of Modern and Contemporary art at the Tucson Museum of Art. “With that in mind, [Schenck’s art] opens up Western audiences to a new way of looking at the West. … Bill Schenck’s work does have a sort of nostalgic, romantic look about it, but he does it in a way that is intriguing and interesting to contemporary audiences.”

Back in the 1960s, however, Western art and cowboy movies might have been the last thing on Schenck’s mind. Although he grew up in Wyoming, his taste in art and film was decidedly contemporary and predominantly European. He studied at the Columbus (Ohio) College of Art and Design — “Wow,” he recalls telling his mother, “that must not be very much of an art school if they accepted me.” — and earned a degree at the Kansas City Art Institute. Right before he moved to New York with dreams of becoming an oil painter, Italian movie director Sergio Leone changed Schenck’s thinking, his art, his life.

Leone’s 1960s trilogy — A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad and the Ugly — made Clint Eastwood an international star, revitalized Italian cinema and turned American film-making on its ear, ushering in the Spaghetti Western era. The movies made Schenck reconsider Contemporary Western art, most of which he found “hackneyed, dreary … I can give you a bunch of negative adjectives.” Then he discovered black-and-white movie stills, and Schenck learned to do interpretations of Western cinematic material. “I knew instantly I was going to put a new face on Western art,” he says. “Nobody had made Western paintings coming from the angle that I had.”

Inspired by Warhol, with whom Schenck had worked briefly in 1966, Schenck became a star. He was Contemporary Western, Southwestern Pop and on the fringe of Photo-realism. He had his first solo show in New York in 1971, found representation in Brussels, Zurich, Paris, London and then …

“Just as quickly as I rose to fame, it faded away. By ’74, ’75, I was struggling to make a living again.”

Schenck left New York and returned to the West, where he split time painting outside of Jackson, Wyoming, and in Phoenix, Arizona. When he discovered team cattle-penning competitions, which morphed into ranch sorting, Schenck moved to Santa Fe in 1997. He put aside paintbrushes and turned to photography.

“I thought I was done painting Western,” he says.

But Schenck came galloping back.

When a client in France commissioned Schenck for three movie paintings, the artist “was just up and running again.”

“A hundred and sixty paintings later,” he says, “I’ve got millions of ideas.”

New paintings can be found at galleries in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming, and his studio is full of works in progress. He’s doing smaller work — usually 11 by 14, 14 by 18, 16 by 20 inches, while scaling up some — and plenty of them. “I did about 1,200 paintings from 1970 to 2008,” he says. “I bet I can double that in 10 years.”

He has found new inspiration in his photographs, Arizona Highways, and the art of Dixon, Mell and the Taos masters.

“He’s started to do more what we call classic landscapes,” says Mark D. Tarrant, director of Jackson’s Altamira Fine Art. “They’re almost photorealistic, but then they become something else when he gives them his treatment. His palette has changed. He’s exploring palettes that he has not used in the past.”

With roughly 500 Westerns in his video collection, he’ll still touch on movies. Among his favorites: Leone’s trilogy, Ford’s My Darling Clementine, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, Tommy Lee Jones’s The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, Mann’s almost forgotten Devil’s Doorway and the 1925 silent epic The Vanishing American.

“I’m not that interested in Western history,” he says. “I’m drawn to the Western myth.”

“I personally love the American Western mythos,” Tarrant says. “But I like Modernists. I like how Modernists handle the energy, the drama they bring to it. That’s what Schenck does.”

Santa Fe-based novelist Johnny D. Boggs knows something about Western cinema, too. His book Jesse James and the Movies comes out later this year from McFarland & Co.; he’s working on Billy the Kid and the Movies; and he turned Bill Schenck on to Devil’s Doorway.

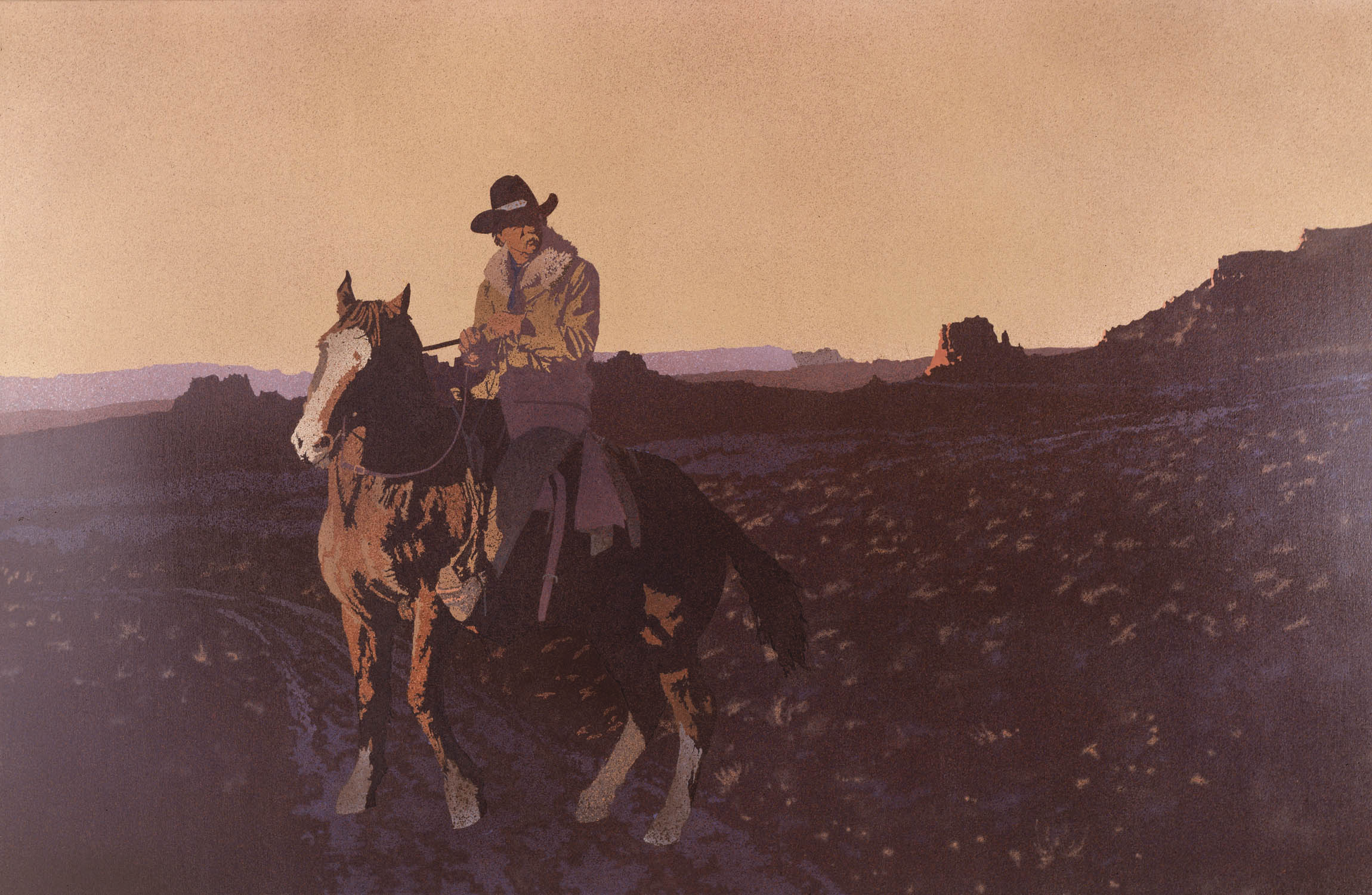

- “Untitled” | Oil on Canvas | 50 x 80 inches | 1973

- The artist saddles up his horse, Badger. Photo by Johnny D. Boggs

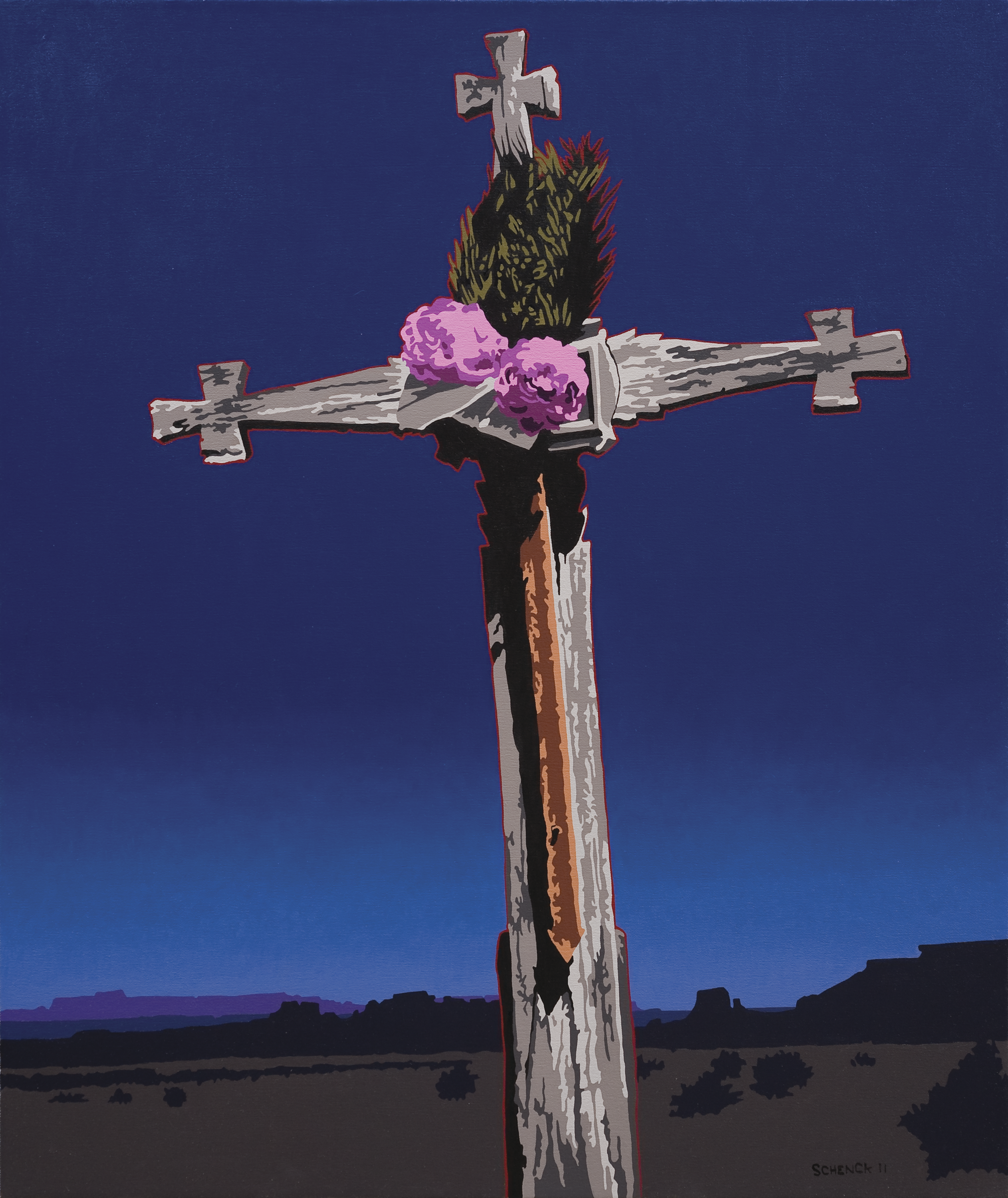

- “From Here to Eternity” | Oil on Canvas | 38 x 32 inches | 2011

- “Mavericks in the Canyon” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 36 inches | 2011

- “Justified” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 16 inches | 2011

No Comments