01 Sep The Rise and Fall of Drop City

AT THE SITE WHERE SOUTHERN COLORADO'S DROP CITY ONCE STOOD, all evidence of one of the first and most celebrated communes of the 1960s has dropped off the face of the landscape.

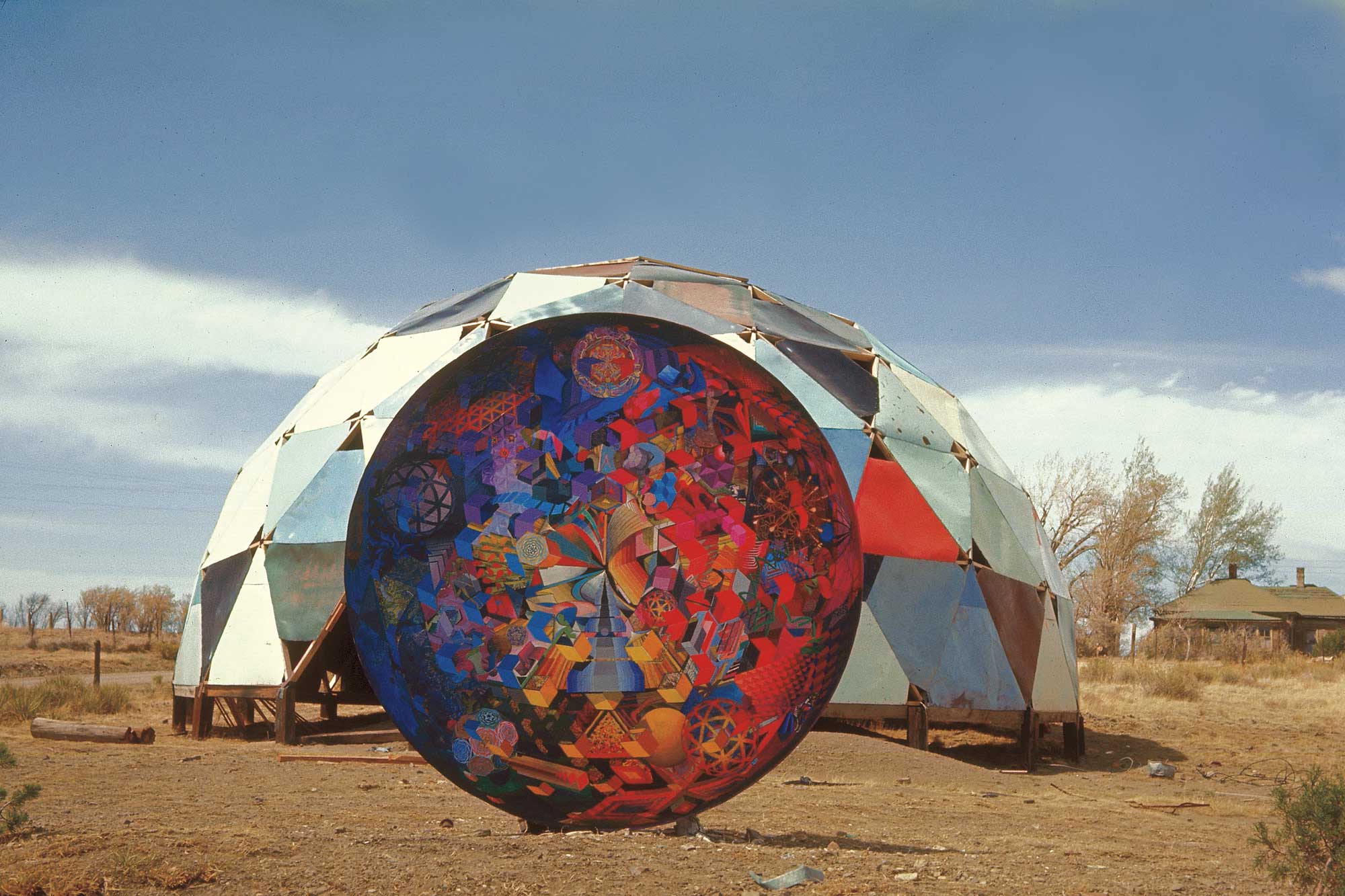

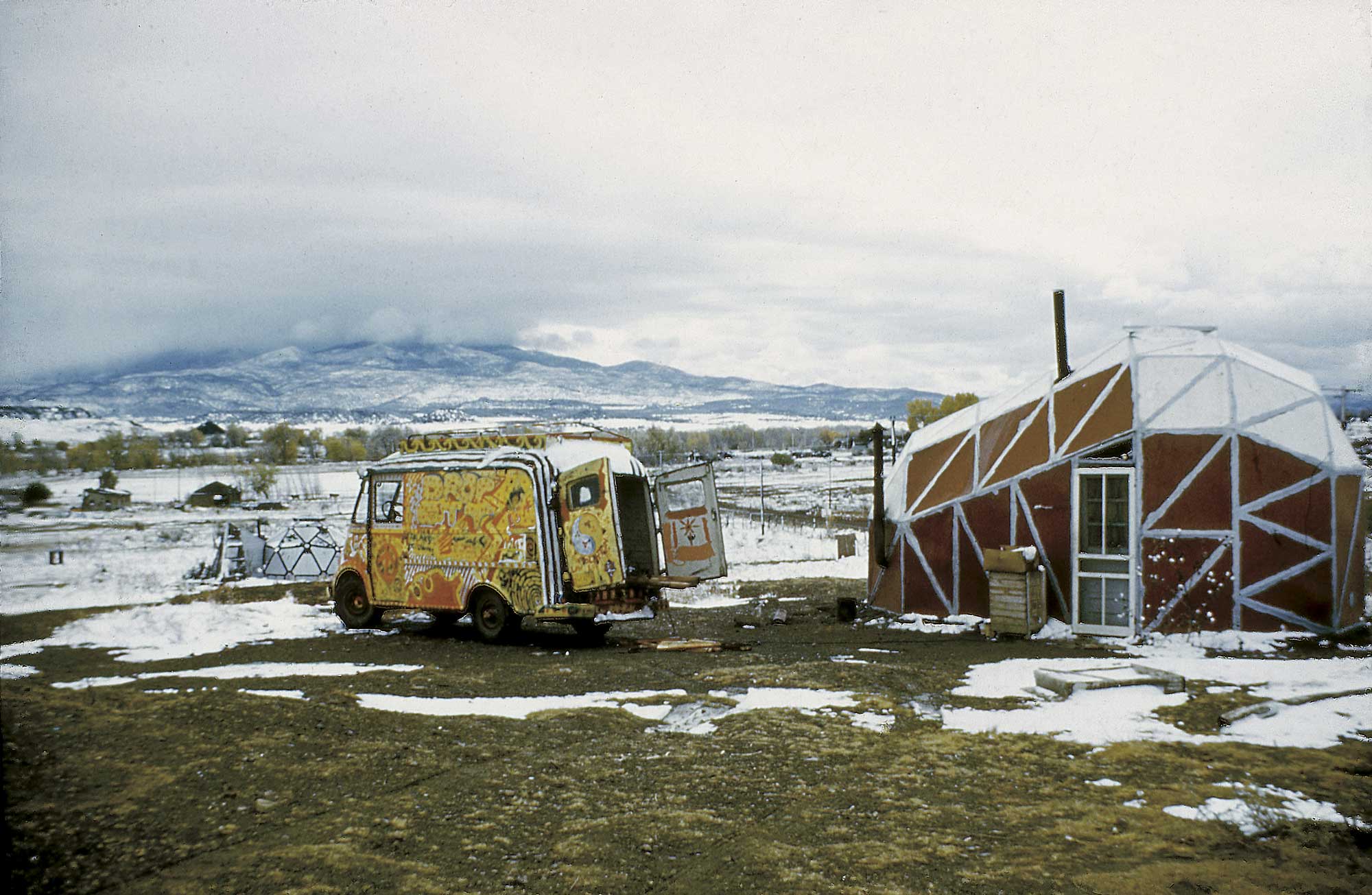

Once in this rural area known as El Moro, just north of the old mining city of Trinidad, its idealistic young residents had built their own Buckminster Fuller-influenced, multi-colored, geometric domed structures. Devotees of environmentalism and avant-garde arts, they used chopped-up car roofs for building material, experimented with passive solar heating and built a futuristic theater dome intended for panoramic movie projection.

Drop City received international press coverage and flocks of visitors, since it was near the state’s major north-south interstate, I-25. And it also won a $500 Dymaxion Award from the world renowned architect, visionary thinker and geodesic-dome champion Fuller, himself, for its “economically poetic architecture.” The most famous photo of it showed a horse grazing in front of the domed buildings — an impressive combination of rusticity and modernism.

Now it’s all gone — abandoned more than 30 years ago. By 1973, it had become “the world’s first geodesic ghost town,” in the words of one of its three founders, Clark Richert. Today, the seven acres it once occupied look too cluttered and dangerous to explore. A trucking and earth-moving company has what appears to be a collapsed hangar there, with some trucks parked on the property. A dog outside a separate house barks ferociously and doesn’t let up. It does not encourage drop-ins.

And yet, Drop City is hardly forgotten. In many ways, it’s never been more popular — not even in its heyday, which lasted from 1965 into the early 1970s. Right now, a documentary and major museum exhibit about it are both in the works. They follow an ever-growing number of books and magazine articles that discuss, remember or in some way make reference to the commune. These include T. Coraghessan Boyle’s best-selling 2003 novel Drop City; communard John Curl’s 2007 Memories of Drop City; and last year’s Spaced Out: Crash Pads, Hippie Communes, Infinity Machines, and Other Radical Environments of the Psychedelic Sixties by Alastair Gordon.

In addition, 2001’s The House Book — a global survey of 500 architecturally significant homes — included Drop City, even though it no longer exists. In fact, so great has interest been lately that a Denver rock band changed its name to Drop City and Trinidad brewpub created a Drop City beer.

“Precisely because there’s nothing left, there’s this kind of magic around it,” says Adam Lerner, director of Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art. It is organizing a show tentatively called Deep Structure: The Ever-Present Legacy of Drop City for the 2011-2012 season. “It has a kind of legendary status, given how ephemeral and utopian it was. There’s something beautiful about attempts to imagine a different architecture for civilization, to reject the square box and try to create something from scratch.”

Indeed, the memory of Drop City drew several hundred people to a Colorado Historical Society-sponsored symposium this summer in Trinidad, where Richert and filmmaker Joan Grossman spoke. Trinidad, with a population just over 9,000, is the last Colorado city of any size before crossing I-25 into New Mexico. It is hilly and old, trying to re-emerge as an arts/tourist enclave after spending the better part of the 20th century as a rough mining town. When Drop City existed on its northern fringe, people didn’t know what to make of its strangeness.

“I was expecting maybe 20 people at a library,” Grossman says. “I think Drop City remains a mythologized curiosity for the people in Trinidad — what was this thing that sprung up in a fairly out-of-the-way community? It has remained something people really wondered about.”

She and co-director Tom McCourt, a media studies professor at Fordham University, hope to have a rough cut of the film done this year. They have interviewed most of the dozen or so primary residents, and have been able to obtain original footage shot by another of the commune’s founders, filmmaker Gene Bernofsky.

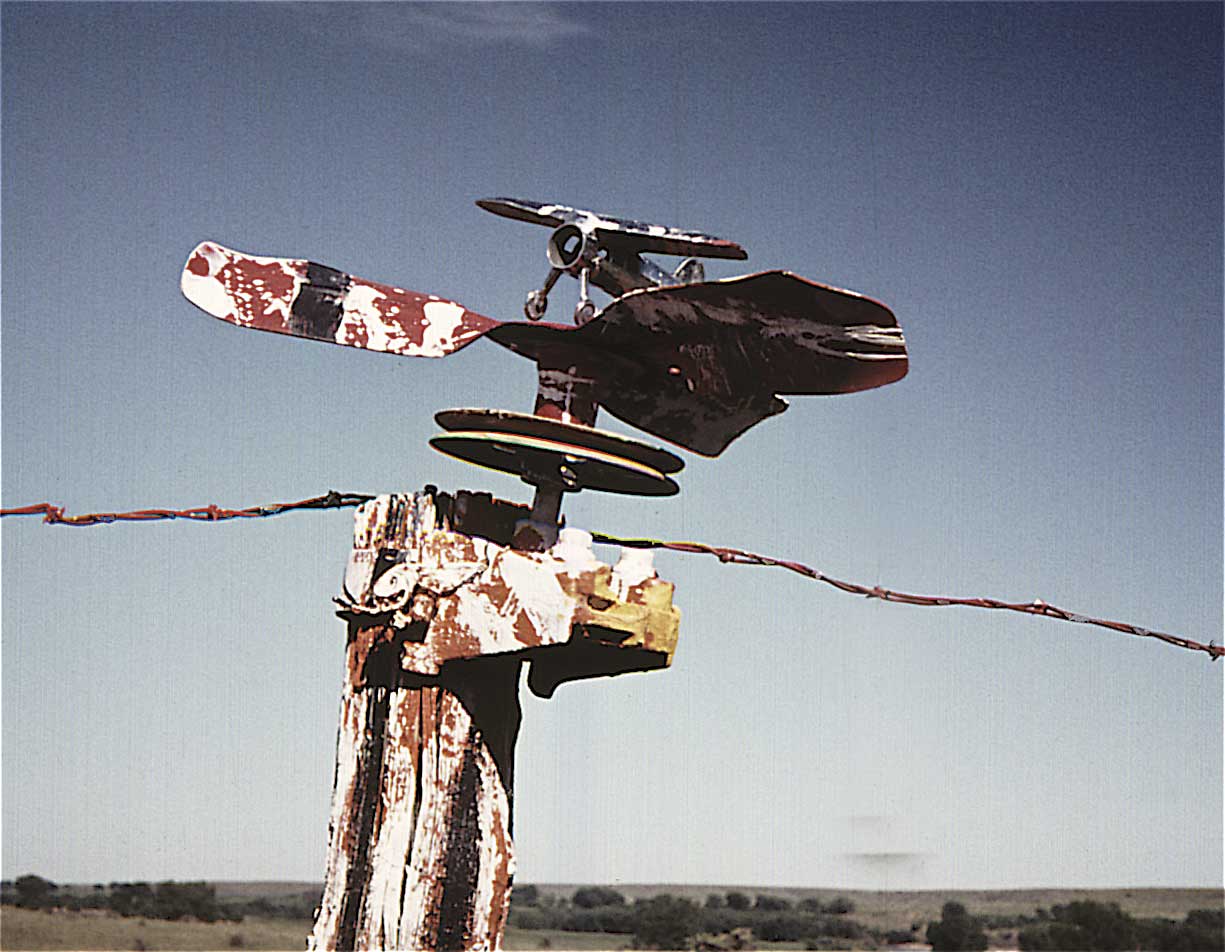

By the way, Richert says, the name Drop City does not refer to dropping acid (LSD) or dropping out of society, like drug guru Timothy Leary advocated at the time. It originates from a time in the early 1960s when he and Bernofsky, as fellow students at University of Kansas, practiced something they called “Drop Art.” From their apartment building, they would drop painted rocks (and other things) on the sidewalk below and study the responses of passers-by.

“It fascinated us,” says Richert, a Denver-based, geometry-oriented painter and also head of Rocky Mountain College of Art & Design’s painting program. (He also maintains a Drop City page on his Web site.) “We called them ‘droppings’ — like Happenings — and ‘Drop Art’ because it rhymed with Pop Art,” he explains. “And everything we did after that we called ‘droppings’. So Drop City was a work of Drop Art. It was a community of artists.”

Richert, Bernofsky and the latter’s wife, JoAnn, got the idea for a commune as early as 1964 in Lawrence, Kansas. But then Richert and a friend who eventually lived at Drop City, Richard Kallweit, heard Fuller speak at the University of Colorado in Boulder and got the idea to live in a domed settlement.

They pooled almost $1,000 and started looking for a suitable space. “When we found this property, it had just rained and it was really green,” Richert says. “They told us we could have it for $500, and we bought it on the spot.” The Bernofskys bought the land; the rest of the money went toward utilities and the first structures.

Many of the core group used playful pseudonyms like Peter Rabbit, Drop Lady and Larry Lard. All were interested in how creativity, life and work (not necessarily a job) could be intertwined into a new society. After the first residents built three geodesic-related domes, a New Mexico engineer, Steve Baer, helped design newer ones based on a zonohedron — a polyhedron-type geometric shape easier to assemble.

Drop City residents also found time to create their Ultimate Painting — which had a motor and spun from a ceiling as a strobe light shined on it. It was displayed at the Brooklyn Museum and in Paris before disappearing.

Eventually, the crush of media attention took its toll and the core group all left. But many continued with the arts.

In the 1970s, Richert, the Bernofskys, Kallweit and another former Drop City resident, Charles DiJulio, started a Boulder art co-op called Criss-Cross, devoted to “pattern and structure” paintings. Baer started a New Mexico company called ZomeWorks, inspired by his Drop City work. John Curl went to New Mexico to do social work at an Indian reservation, later moving to Berkeley to join a woodworking cooperative and write. His second book about Drop City comes out this year — a history of communes and co-ops called For All the People.

“I and many other people thought it would turn out to be a long-term family place and I could spend the rest of my life there,” says Curl, who lived in Drop City with his girlfriend (now wife), Jill, from 1966-1969. “As it turned out, it became clear it would be like most 1960s communal groups were: an episode in people’s lives. Everybody lived there for a while and moved on.”

Moved on, yes. Forgot? Hardly.

Steven Rosen is a Cincinnati-based arts writer who worked at the Denver Post — as art and movie critic — for more than a dozen years. He has also contributed to The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Modernism and Cincinnati CityBeat, and maintains a blog at www.stevenrosenwriter.blogspot.com.

- Two of the domes built by Drop City residents at their commune near Trinidad: the Hole and the Complex (1967).

- The Cartop Dome and Dropper van (1967).

- The Kitchen Dome (1966). Figures right to left are Richard Kallweit, Clark Richert, unidentified woman, Peter Douthit, Kathy Douthit, Judy Douthit, unidentified woman (possibly Jill Curl) and unidentified woman.

- John Curl beside first dome (1967).

- The Theater Dome under construction; statue is The Sentinel by Manuel Neri (a gift to Drop City) (1966).

- Drop Art (1965) courtesy of Gene and JoAnn Bernofsky.

- Unidentified woman (possibly Dee Flippen) inside the Cartop Dome (1966).

- Drop Art (1965) courtesy of Gene and JoAnn Bernofsky.

- Richard Kallweit atop frame of the Theater Dome (1965).

No Comments