29 Dec The Space Between

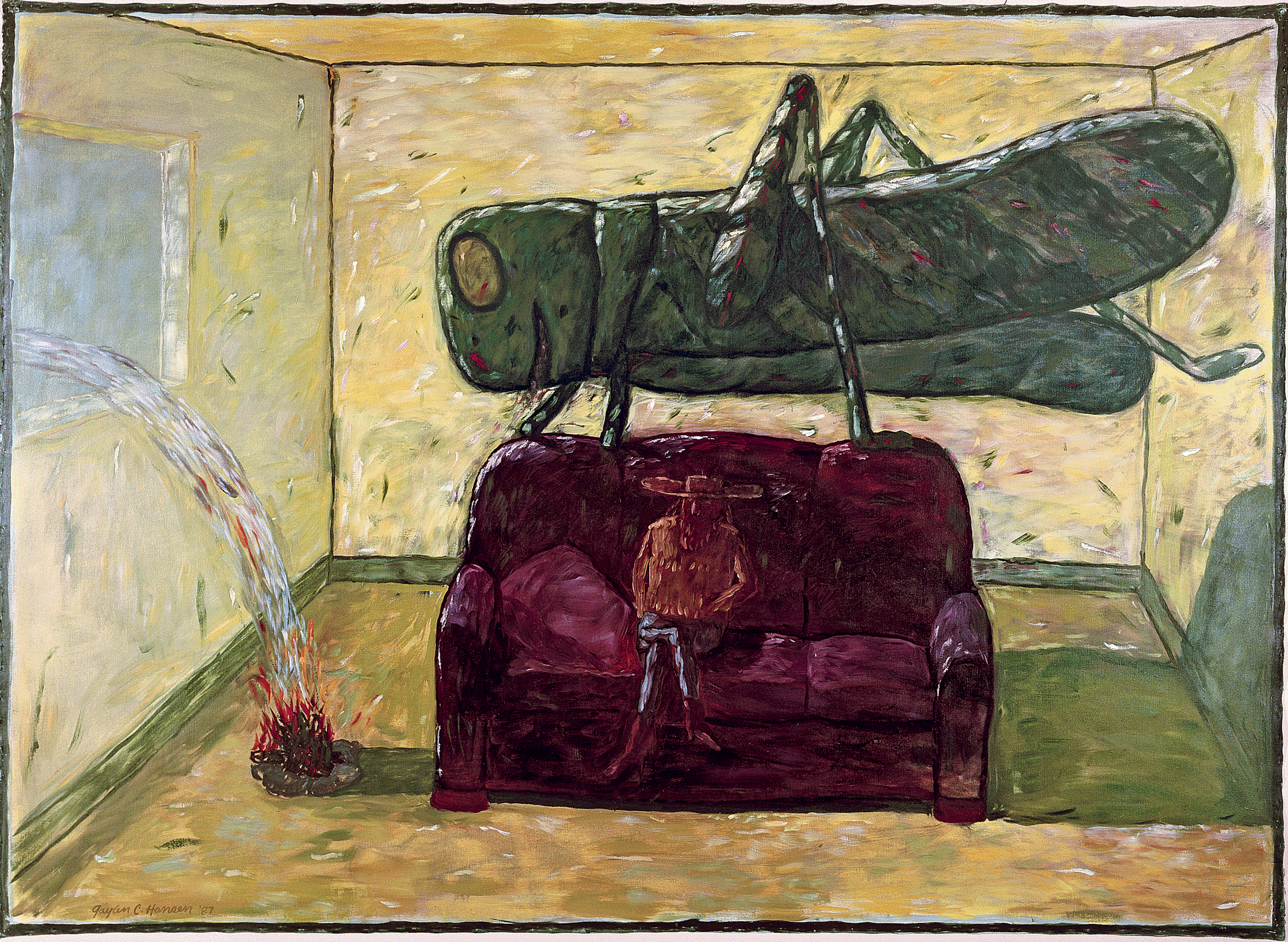

NOT LONG AGO, I secretly left a picture book of Gaylen Hansen’s paintings on a table in a small coffee shop where I live in Bend, Oregon. For reasons of my own, I wanted to see peoples’ reactions. Hansen is the 89-year-old Neo-Expressionist from Palouse, Washington, famous for his over-sized grasshoppers, incongruous ducks and dog heads, and a diminutive cowboy figure the unflappable seeker Hansen calls “the Kernal.” Without exception the response to the book was curious delight. There was an immediate and positive response to the images, as well as a good deal of amused laughter. More surprising was the friendly deconstruction that followed, often quite insightful, and this from people who were not frequent viewers of fine art. What I discovered is people were not only finding joy in the work, but thinking about it from a bemused, contemporary and non-judgmental point of view. Having spoken with Hansen in his studio the week before, I knew this is exactly the kind of response he was shooting for.

On the day I met Hansen he greeted me in cotton pants, sneakers, a fire-engine red fleece and black fleece cap with tufts of white hair sprouting out from underneath it. It was like encountering a 3-D Kernal with rimless glasses and a wardrobe change. After pleasantries, Hansen escorted me to his studio, a modified garage where a forced-air heater cycled on and off noisily and paintings that had not made the grade were turned upside down on the floor serving as tarps. Sitting across from me, Hansen patiently answered my writerly questions, taking time to puzzle out the best way to put things. Humor is often cited as one of the main ingredients of Hansen’s work, and as our conversation unfolded I would now and again catch a glimpse of playfulness in his eyes, a mischievous, impish twinkle that hinted at boyish imprudence and a not-so-closeted delight in bucking the norm.

Gaylen Hansen, I surmised, is a man who might well enjoy a practical joke, which made me wonder if his paintings are not in some way a derivative of this — Contortionist in particular, came to mind. By the time I left, however, perspective is the word that I came away with. Hansen sees things the way they are, and then paints them the way he wants, foregoing scale, laws of nature and even common sense. The perspective he has gained, I realized, is not simply from a long life, but is that of a learned man endowed with a forgiving and even-handed nature.

For Hansen, painting relates to mood and feeling. “The overall effect of the painting, the way it makes you feel,” he said, “is the main thing.” As an example he pointed out Kernal with Fire and Wolves, a 60-by-72-inch oil on canvas, which shows the Kernal cooking at a campfire, the smoke coming into his eyes and a set of wolves materializing out of the smoke behind him. “Everybody loves that painting,” Hansen said, “because they know that’s the way life is. You sit down to cook your supper and the goddamn smoke blows in your eyes and you’ve got a pack of wolves behind ya.”

Smoke or no smoke, Hansen’s paintings are the visual equivalent of Zen koans; they are not so much a punch in the gut, but a slap on the forehead. Likewise, his answers to my questions looped and spiraled, but always came back to the original point (and sometimes long after I’d forgotten what the point was). As he spoke he talked about his work from one of two perspectives: the creator, pointing out brushwork and texture, composition, subject and ground relationships; or, more often than not, the viewer, as if he was a stranger who just wandered in off the street.

“Now that’s a damn good painting,” he might say, but without the least hint of braggadocio — and seldom do you hear an artist say such bland and bold things about their own work. In the same vein, Hansen wasn’t apologetic when admitting ego was involved. “Of course there’s ego involved,” he said, but he said it in such a way as to imply he’s human and how could it be otherwise? In the end I was left with the impression that Hansen’s ego was about as involved with the work as the Kernal was with smoke that blew in his face.

At one point Hansen held up his index fingers, spacing them about a foot apart. “If I hold up my two fingers here,” he said, “most people see here’s one finger and here’s another finger, but they won’t see the space in between. My work is all about that kind of stuff, the space between.”

Hansen’s paintings are indeed about the space between: the space between the ears. For all their simplicity, humor and folktale quality, Hansen’s paintings are deceivingly intelligent. Peter Stremmel, owner of Stremmel Gallery in Reno, Nevada, says it plainly, “[Hansen’s] work can be perceived on two different levels. One is the superficial level where they are delightful, humorous and people take great pleasure in them. And then I think at another level these paintings have a certain intellect and sophistication that I find are very, very compelling, and these are some of the ones that at first glance appear sort of crudely painted.”

Linda Hodges, Hansen’s long-time friend and owner of Linda Hodges Gallery in Seattle, Washington, agrees. “For me I’ve never seen anything like his work. It’s very fresh, it’s very original. … It’s a quirky personal style, yet very, very sophisticated in the formal abilities, the way he places paint on the canvas and puts compositions together. At first they might seem very simple, but they are very sophisticated.”

Placement of things is critical for Hansen. Early on Hansen and a friend would experiment with placing objects on a table: lining them up, scattering them, putting them along one edge, covering them with a cloth. What they found surprised them. “We recognized that different configurations had different feelings,” Hansen said. “Lining things up produced a different feeling than scattering them. It isn’t as though there was a right way and a wrong way; these were just possibilities. But amongst them all, there were certain arrangements that seemed to be stronger or more interesting.”

One of the most interesting aspects of Hansen’s work is his disregard for scale. “In a lot of my paintings I haven’t kept everything in scale,” he said — no twinkle in the eye, no you-know-what-eating grin, he kept a perfect poker face. I almost couldn’t believe it. Giving a talk in Seattle, Hansen was once asked why he painted a giant grasshopper, a grasshopper that big on the back of a sofa. Hansen’s response? “That grasshopper is the right size. It has to be that big. Otherwise there’s no point to the painting.”

Hansen grew up on a farm in Utah. By the age of 9 he was plowing with draft horses. Once he began painting, he would show in New York, Los Angeles, Berlin. The New York Times called him a must see. Hansen taught for 25 years at Washington State University in Pullman. Stremmel calls him, “Probably the most important contemporary artist in the Pacific Northwest.” But Hansen has never been after fame, he has just painted what he wanted to paint — and the freedom shows. It’s like when he walks with his wife, Heidi Oberheide, in the hills around Palouse. Maybe he sees his neighbor’s dogs in tall grass, only the heads showing, and he goes home and paints that, just dog heads. Then he places them on the hills. Why not? It’s a new perspective. A slap to the forehead. A gut check and belly laugh. Something to enjoy and think about. In other words, Gaylen Hansen through and through.

Charles Finn is the assistant editor of High Desert Journal, and his writings have appeared in a wide variety of literary journals, anthologies, newspapers and consumer magazines. He lives in Bend, Oregon, with his wife, Joyce Mphande, and their two cats, Pushkin and Lutsa.

- “Putting Up the Stars” | Oil on Canvas | 72 x 84 inches | 1988

- “Kernal with Maroon Sofa” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 84 inches | photo: Jens Selvig

- Painter Gaylen Hansen in the studio. Photo: Zach Masur

- “Contortionists” | Oil on Canvas | 60 x 72 inches | 1991 | photo: Robert Hubner

- “Dog and Magpie” | Oil on Canvas | 66 x 72 inches | 1989

No Comments