10 May The Taos Legacy

The Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios program offers visitors a chance to experience the settings where great paintings and sculptures were created, highlighting 44 places across the U.S. where noteworthy artists of the past once lived and worked. As part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the organization leads visitors to sites as diverse as the Berkshire Hills estate in western Massachusetts, where Daniel Chester French sculpted the 16th U.S. president in 1920 for the Lincoln Memorial; the Arts and Crafts bungalow in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where Grant Wood painted American Gothic in 1930; and the humble wooden cabin on Melrose Plantation where, during the first half of the 20th century, African American folk artist Clementine Hunter recorded quotidian plantation life in vibrantly colorful scenes.

One of these destinations, however, stands in a class all its own. In the heart of Taos, New Mexico, the Couse-Sharp Historic Site presents the studios of two key American painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Eanger Irving (E.I.) Couse and Joseph Henry Sharp, along with the home where Couse and his family lived.

Beyond that, the site also preserves the birthplace of an American art movement: the Taos Society of Artists. Despite the group’s disbandment 94 years ago, the movement’s influence still resonates and promises to gain even greater impact through a soon-to-open, state-of-the-art research center. Not to mention the fact that the Couse-Sharp Historic Site features, within its 2-acre compound, breathtaking cultivated grounds that are referred to as “the Mother Garden of Taos.” And beyond its confines, vistas sweep southward across 20 acres of protected pastureland to the Truchas Peaks some 30 miles away.

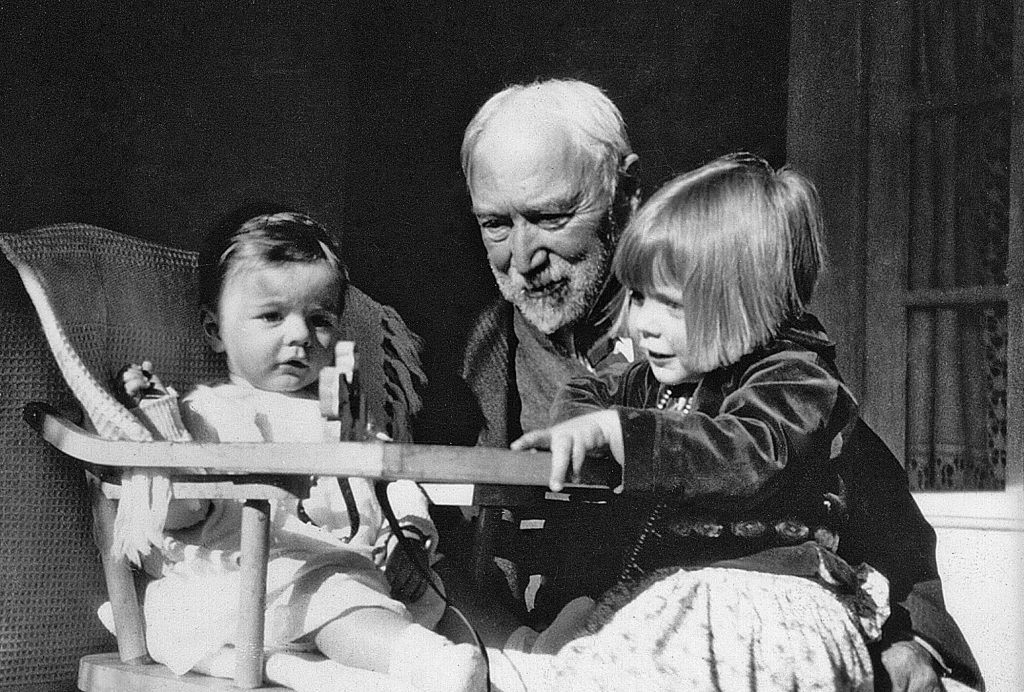

“It’s a spectacular view,” says art historian Virginia “Ginnie” Couse Leavitt, who spent the first six years of her life here in the home of her grandparents E.I. and Virginia Walker Couse, playing in the garden her grandmother planted. She also wrote her grandfather’s definitive biography and, over the past 20 years, has led the establishment and revitalization of the site and its celebration of the artistic legacies of Couse and his best friend Sharp.

Couse and Sharp followed parallel paths for the first few decades of their lives. Both were born in the Midwest, showed early talent, and began training in respected stateside design institutions. In their early 20s, the two men continued art studies in Europe, and they both attended the respected Académie Julian in Paris, though their times there did not overlap. Both lived in Europe for several more years before returning to the U.S. And significantly, both were long fascinated with portraying Native Americans and their culture.

Sharp was the first painter to discover Taos, and he and his wife, Addie, spent summers there and in Santa Fe starting in 1897. Couse’s artist friend Ernest Blumenschein told him about the wonders of Taos in May 1902, and two weeks later, the artist, his wife Virginia, and their young son Kibbey took up summer residency there.

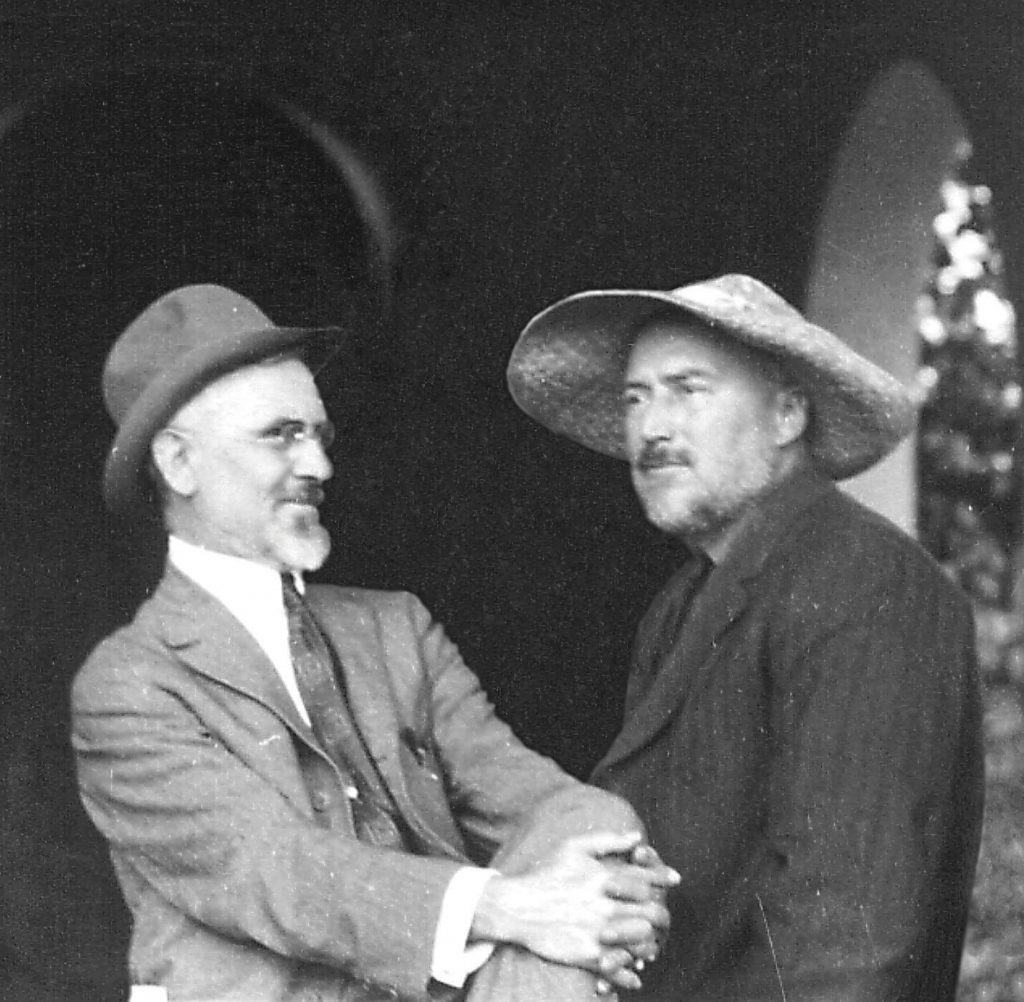

Couse and Sharp met for the first time in the summer of 1906. Two years later, Sharp and Addie bought property on Kit Carson Road, just east of Taos Plaza, and the year after that, Couse bought a 70-year-old house next door. Both men built large studios on their properties, sharing not just a deep friendship but also a serious dedication to their work and a love of collecting Native American crafts and clothing that figured so prominently in their art. Sharp’s wife Addie died in 1913, and, two years later, the artist married her sister Louise. The couple, who had no children, were like second parents to Kibbey Couse, whose own three children called them “Uncle Henry” and “Aunt Louise.”

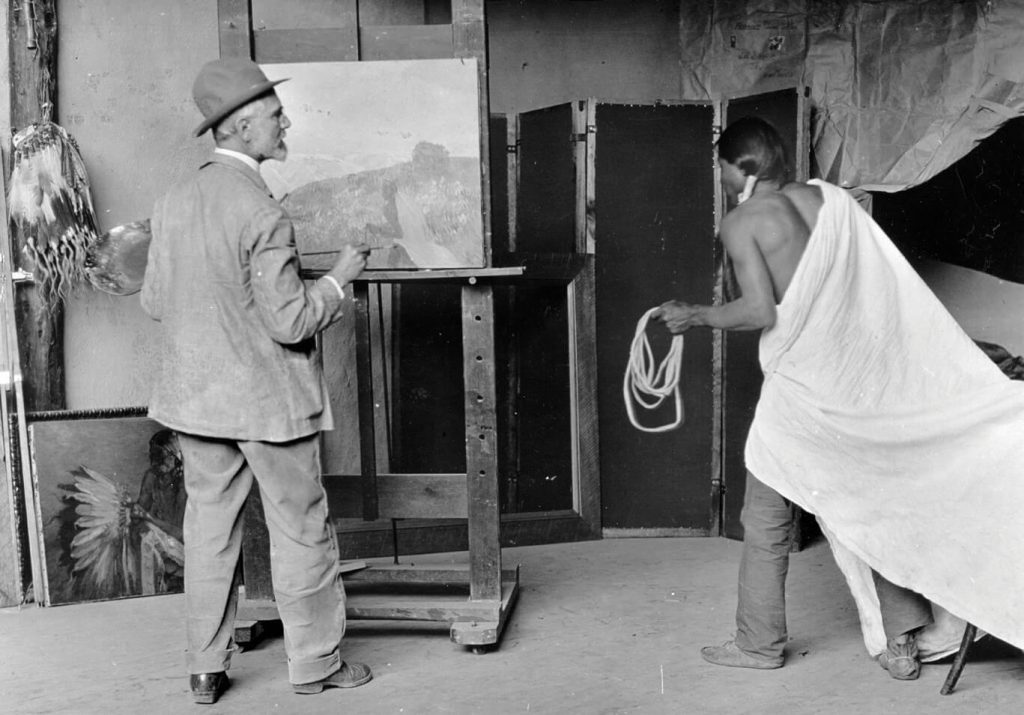

The paintings produced by the two men and their fellow local artists became the expression of “a lived experience that was wholly unique in the West,” says Davison Koenig, the executive director of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site, who was initially hired to restore Sharp’s second studio on the site in July 2015 after 11 years as curator of exhibits at the Arizona State Museum.

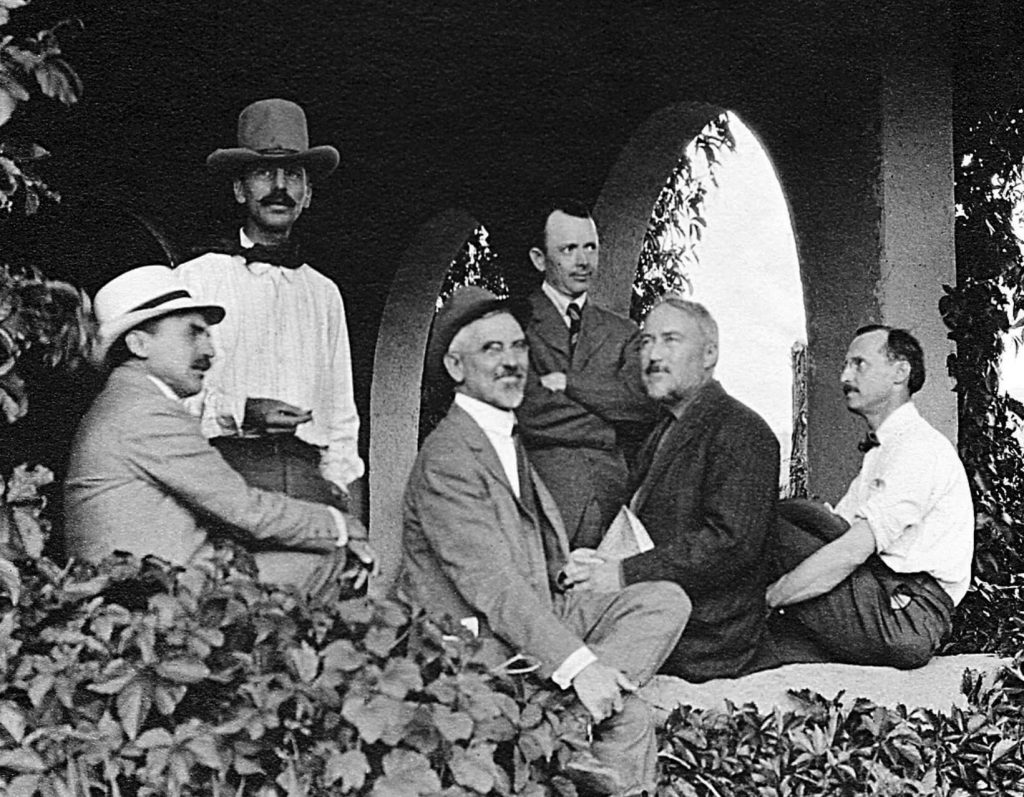

Inspired by a common purpose, Couse and Sharp joined with friends and fellow painters Blumenschein, Bert Phillips (both of whom had first painted in Taos in 1898), Oscar Berninghaus, and W. Herbert Dunton to form the Taos Society of Artists on July 19, 1915, coming to be known informally as “the “Founders.” Numerous archive photos from the time show them all posing nonchalantly in Virginia Couse’s lush garden, and others present Sharp and Couse there with their easels set up in the open air, taking advantage of the light and beauty of their surroundings.

The Taos Society of Artist’s reputation spread rapidly. They held successful exhibitions nationwide — and some major collectors, including John D. Rockefeller and Thomas Gilcrease, even made the arduous overland trek to Couse and Sharp’s studio doors. The group’s roster swelled with other top artists of the day, including Victor Higgins, Walter Ufer, E. Martin Hennings, Julius Rolshoven, Kenneth Adams, and the only female member, Catharine Critcher.

As far as art movements go, the Taos Society had a good run. While members came and went over the next decade-plus, the group ultimately disbanded in 1927. Couse and Sharp stayed on in Taos. In 1936, Couse died at the age of 70. Sharp continued to live in his house and paint in his studio until his death in 1953, at age 93, while on a trip to California.

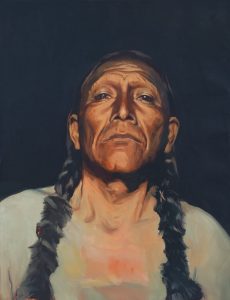

Meanwhile, says Koenig, “East Coast graduates rewrote American art history with a New York bias, and once Modernism arrived, the Taos Society got written out of the larger history of American art.” Then, in the 1980s, a grassroots resurgence of Realism — fueled in part by plein-air painting and by art celebrating the cultures and landscapes of the Southwest — began to take hold. And after the dawn of the new millennium, a new generation of contemporary Southwestern artists, including Mark Maggiori, Glenn Dean, Brett Allen Johnson, and Logan Maxwell Hagege, acknowledged the inspiration of their forebearers a century before. A revitalized interest in and appreciation for the Taos Society of Artists and their work had begun.

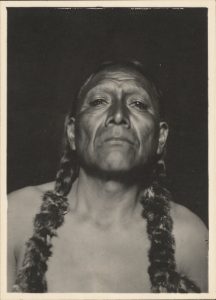

Ginnie Couse Leavitt and her husband, Ernie, a curator at the Arizona State Museum, began spending half the year in her grandparents’ home after Ernie retired in 1989. “We discovered what a brilliant treasure trove was here,” she says. “Our family never threw anything away.” That included such treasures as her grandfather’s collection of artifacts used in his paintings, along with some 11,000 nitrate negatives and the same number of contact prints Couse developed and printed in his home’s darkroom, mostly figure studies of local Native Americans who modeled for his work.

In 2001, the Leavitts led the formation of the nonprofit Couse Foundation to oversee and support the entire property, which on September 28, 2005, received recognition on the National Register of Historic Places. The foundation purchased the site from the family in 2012. Since then, an ambitious plan has begun to be realized, including such early initiatives as the historically accurate restoration of Sharp’s studio led by Koenig. Ernie died in 2015, and in 2019 Ginnie moved to Taos full-time, devoting herself to the work of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site.

“Ginnie is the real deal, and this place is the real deal,” says Rich Rinehart, a foundation board member for seven years now, and its president since June 2019. “People who experience the site say there isn’t anyplace anywhere else like this. They’re drawn to it.”

Ginnie neatly sums up the ways in which the place is unlike any other historic site or museum: “First, we have preservation here, because we keep Couse’s home and studio exactly as it was when he worked here. Next, we have the restoration of Sharp’s second studio, which Davison restored to the way it was when Sharp was using it. Then there’s the renovation, with our new archive and research center.”

By that, she’s referring to The Lunder Research Center, a state-of-the-art, 5,000-square-foot museum facility under development as part of the renovation and expansion of the historic building where Sharp once lived. Slated for completion this summer, with a grand opening scheduled for 2022, the center is destined to be an unparalleled archive for documents and artifacts related to all members of the Taos Society of Artists, along with their original works of art, a research library and repository for scholarly works related to them, and ethnographic items from the Native American peoples they painted. Taos Society heirs and scholars alike have already begun to donate enthusiastically.

Koenig sees this as a final element in transforming the Couse-Sharp Historic Site into “a living campus,” which will also see interns, artists, and scholars spending time working on site. Indeed, Mark Maggiori, who recently moved to Taos, spent a four-month residency there last summer, creating a transformative series of paintings inspired by Couse’s photographs. He’ll be showing them in The Lunder building’s gallery starting on October 2.

“There really is nowhere else where you can viscerally step into the world these artists inhabited,” says Koenig, gazing out across a peaceful setting that now welcomes guests again as life in New Mexico returns to some semblance of normalcy after the pandemic. “This is not just a Taos art story. It’s an American story, a national narrative. And one of our most important missions is to tell that story to the country.”

No Comments