01 Feb The Ties That Bind Us

MICHAEL COLEMAN HAD GAINED FAME as a Western and wildlife painter by the time his young sons were able to climb into his lap for a closer look at his works.

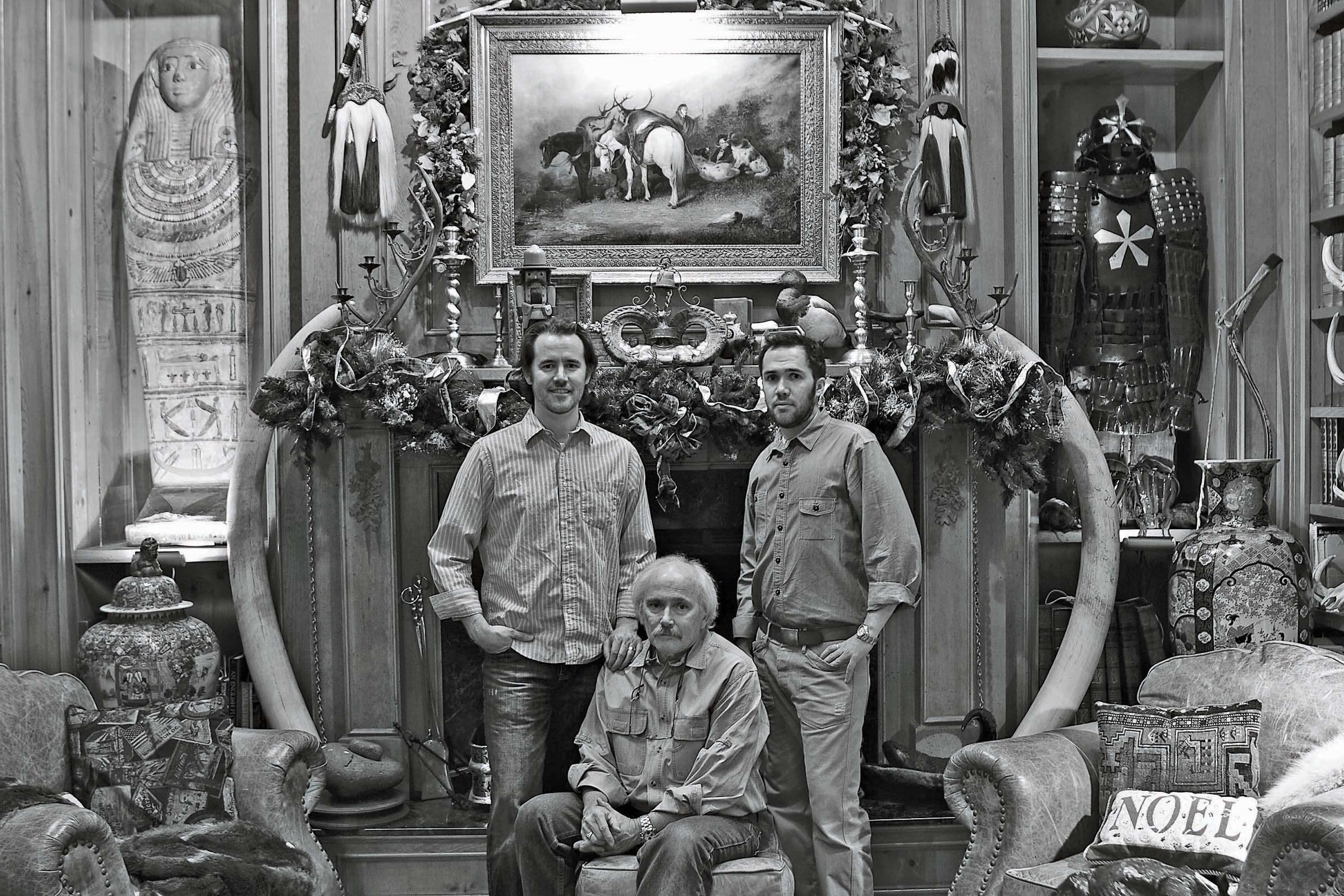

Today, more than three decades later, two of Coleman’s sons, Morgan and Nicholas, are accomplished artists in their own right and the Coleman studio in Provo, Utah, is incomplete without the trio toiling to produce paintings.

The Colemans are part of what art scholars and gallery owners say is a relatively exclusive group of successful artists — those distinguished ranks also include Daniel Smith and son Adam Smith as well as Stephen LeBlanc and daughter Renee Buller — whose rare talents and exceptional skills have flowed from one generation to the next.

The pattern raises the perennial — and tantalizing — question of whether the creative children of celebrated artists inherit their skills or if they are cultivated by association.

Scott Jones, general manager of Legacy Gallery, with showrooms in Jackson, Wyoming, and Scottsdale, Arizona, did not experience a moment’s doubt about representing Morgan Coleman right along with his famous father. But Jones has given substantial consideration to the origins of artistic aptitude.

“To me, it’s a fascinating question,” he says. “I’m not sure it’s in the genes as much as it is in the environment. The child is exposed to art, grows up with it — and either falls in love with it or puts it aside.”

Michael Coleman, Stephen LeBlanc and Daniel Smith are neither doting dads nor punishing taskmasters: they are mentors, the highest of parental callings. They say contacts in the art market may have opened doors for their children, but only talent could usher them through.

The arc of the artistic careers of Morgan Coleman, 41, who excels at landscapes, and Adam Smith, 27, wildlife painter, took shape amid accomplishments in their chosen first professions.

Less than a decade ago, Morgan Coleman headed a printing business pinned to reproducing many of his father’s paintings, which today sell for tens of thousands of dollars. Though he had dabbled in painting as a college student, Morgan never focused on his talent until 2003 when his wife unearthed his collegiate works in a closet. “She said, ‘Why aren’t you painting like everybody else in your family?’ It went from there,” he says. Adam Smith, a rock band guitarist in his adolescence, was working as a car designer in his home state of Montana by day and artist by night when he decided in 2006 to devote himself to painting.

His works sell briskly, whether at the Jackson Hole Art Auction, at Trailside Galleries, or at the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Western Visions Miniatures and More Show and Sale.

Smith has sought to take the outpouring of approbation in stride, expressing fresh surprise when buyers ask how it feels to be famous — like his father.

“I don’t feel that way,” says the 27-year-old. “I’ll always end up doing art; I’m just fortunate to be able to do something I love for a living.”

It shows. His Mystic Heights, an acrylic, is less a painting than a prayer on the mountaintop amid bighorn sheep.

Maryvonne Leshe, managing partner of Trailside Galleries, credits Daniel Smith for ensuring his son gained the technical expertise required to withstand the rigors of the art market. “Adam’s drawing skill is superior; he’s had a great teacher in his father,” says Leshe. “And he is already such a mature artist at an early age — that doesn’t always happen.”

Nicholas Coleman, 33, and Renee Buller, 27, do not remember making a conscious decision about becoming painters, despite their paths taking shape even as they took their first, uncertain steps.

Buller’s childhood remembrances center on her pastimes of drawing and sketching as her father, already an acclaimed wildlife sculptor, gathered her up for trips into the field to view elk and other creatures in Colorado’s backcountry. “I learned from my dad to attend to the anatomical structure of animals; he gave me that understanding,” Buller says.

Nicholas Coleman was as much caught up with his father’s passion for art as he was with his own enthusiasm for the period in American history that brought westward expansion. His works often depict Native Americans and frontier figures as ruggedly beautiful as the environment they embody.

“I’m trying to preserve the memory, a little piece of the West,” he says.

Like his father and brother, Nicholas Coleman is a master of light. Degrees of white weave through the sky and prairie in his portrait of pioneers, Willie Handcart Company – A Late Start. That compares to the backlit stream in Forest Falls, by Morgan Coleman, and Michael Coleman’s sun-drenched fox in Light in the Forest.

Daniel Smith, 57, the 2011 featured painter for Western Visions, is known for making stark statements with the muted lighting of his paintings. His portrait of a mountain goat, Cliff Hanger, is a masterpiece of subtle coloring that captures a wild creature in a restful moment.

Daniel Smith, whose multiple wins in the prestigious Federal Duck Stamp Contest catapulted him to early honors, abides by the rule that an artist is only as good as his last painting. He moved his family to southwest Montana in 1994 in part to live within viewing distance of the animals that are his inspiration.

He says many erroneously assumed his son learned to paint almost by osmosis. But, in fact, his children spent few hours in his studio. Daniel Smith recognized his son as the painter he would become when asked to critique Adam’s painting of an African lion.

“It looked like I had done it,” he said.

Stephen LeBlanc, too, has watched with tremendous pride as his daughter followed, quite literally, in his footsteps. A one-time mortgage broker and taxidermist, sometime television outdoors guide and full-time sculptor, in 2011, LeBlanc presented to his daughter the best-in-show award he had won the year before at the NatureWorks Art Show and Sale in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“I had tears in my eyes,” says the 56-year-old LeBlanc. “I realized she was well on her way. She is a force to be reckoned with; she will be a lot more famous than I ever was.”

Buller’s paintings illustrate many of her father’s principles about accurately depicting animals and releasing for sale only those works that achieve the highest standard. Wapiti, an oil of a bugling bull elk, demonstrates Buller’s painterly style and her skill in making middle distances masquerade as long views.

LeBlanc’s Black Death, a bronze of a Cape buffalo, is mounted for tabletop display but is far from static. The piece speaks volumes about LeBlanc’s travels to Africa and elsewhere to see creatures he shapes up close and personal.

At 65, Michael Coleman has the advantage of age and a path to success that was paved by the faith, good will and guidance of some of Western art’s leading critics and collectors. Yet the winner of such awards as the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Prix de West is as impassioned today as he was decades ago about nature and its creatures.

“It’s the grandeur of it: the magical lighting, the animals moving through the brush, the orange glow of the sun setting after a rain, the surface of the rocks; it makes you want to be part of it,” he says.

Coleman celebrates his sons’ successes with the same enthusiasm. He recalls them as children, sitting on his knee while he worked on a canvas. He would mix up paint, give them a brush and let them have at it.

“I just want them to find their own way, to have their own style,” he said.

Adam Warner, owner of Mountain Trails Gallery in Jackson, Wyoming, and Park City, Utah, says that while he may mark Michael Coleman’s influences in the Nicholas Coleman paintings in the galleries, “You can always pick out a Nick and a Mike.”

No matter the generation, the artists share a vision that is anchored in the outdoors and given life by nature, from elemental expression to romantic rendering.

“You have dynamic artists giving rise to dynamic artists. What could be more natural?” says Legacy’s Jones.

- “Light in the Forest” | Michael Coleman | Oil on Linen | 30 x 40 inches | 2011

- (left to right) Morgan, Michael, and Nicholas Coleman

- (left to right) Daniel Smith and son Adam

- “Cliff Hanger” | Daniel Smith | Acrylic | 20 x 40 inches | 2011

- “Willie Handcart Company — A Late Start” | Nicholas Coleman | Oil on Linen | 36 x 48 | 2011

- Stephen LeBlanc with daughter Renee Buller

- “Mystic Heights” | Adam Smith | Acrylic 20 x 36 inches | 2011

- “Wapiti” | Renee Buller | Oil on Linen | 15 x 30 inches | 2011

- “Black Death” | Stephen LeBlanc | Bronze | 31 x 18 x 12 | 2009

No Comments