07 Nov The Wilds of Watercolor

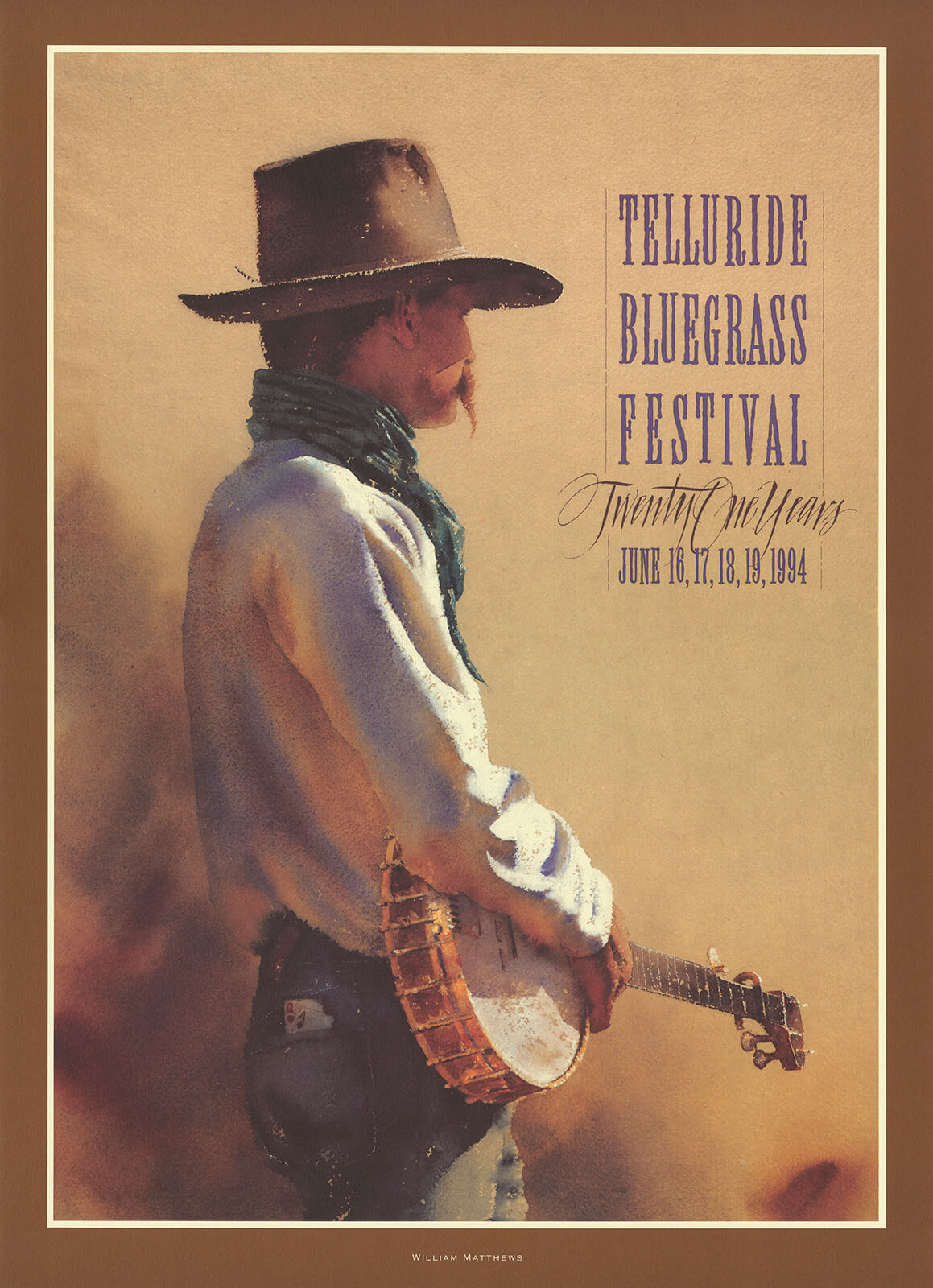

In my home office, hanging square in the middle of a wall crowded with beloved paintings and photographs, is a poster from the 1994 Telluride Bluegrass Festival. I first saw this poster when I was a little girl, maybe 6 or 7 years old, inside the festival’s merchandise tent and appealed to my father, thumbing through CDs nearby, to buy it and take it home.

I was mesmerized by the poster’s cowboy. He typified those mysterious professionals indebted to horses and the wild landscape. He turned away, looking toward some distant horizon that seemed to hold the deep romance of the unknown. I adored the moody tones of the watercolor, with its unexpected purples and soft sepia browns, and admired the fine white line delineating the brim of his cowboy hat. He seemed relaxed, banjo in hand, as comfortable with his instrument as I imagined he was on a horse.

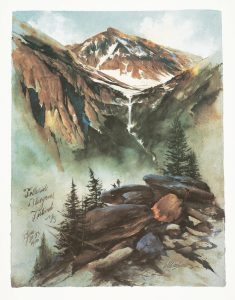

23rd Annual Telluride Bluegrass Festival Poster

Ome Banjos and Mandolins Poster

Since then, that poster has hung on walls in New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Montana, and Maine. When I look at it, I’m reminded of my father and the summer he spent in his 20s working as a cowboy in Pinedale, Wyoming. It reminds me of Telluride, where my dad first visited in 1979 on a date with my mom and the only place he took my family on a rare vacation. That mountain town was his wonderland, where the beauty of the surrounding peaks dwarfed any real-world problems, leaving them for when we “returned to reality,” he would say.

Painted by William Matthews, that poster introduced me to art and its ability to tell stories, ignite the imagination, and assist your soul. And, as it turns out, this was precisely the artist’s intention: Matthews believes that good artwork should be readily available to anyone — little girls included. He views those bluegrass posters he’s painted for 40 years as fine art that’s accessible to everybody.

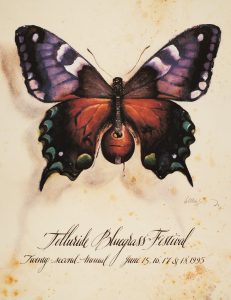

22nd Annual Telluride Bluegrass Festival Poster

Artist William Matthews photographed by his daughter Alistair Matthews in Chicago.

“If there ever was a goal, it’s that,” says Matthews.

These posters and other significant works appear in William Matthews: Decades, a retrospective at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West through April 28. As Matthews’ first retrospective, the exhibit showcases artwork representing periods of his creative life, from 45 album covers, 25 posters, and a series of large-scale Western ties to 100 original watercolors depicting landscapes, cowboys, steelworkers, world travel, and his love of architecture.

Album Cover for Béla Fleck, 2021

“A lot of people know my paintings. A lot of people know my posters. Some people know my album covers. But very, very few people know all of those things together,” Matthews says. “[The retrospective] represents the tangents that are really important. People sort of think of me — accuse me — of being a Western artist, but I don’t think of myself as a Western artist per se. I love painting cowboys, and I love painting the West, and I love all those elements, but that is just a part of what I love. … There are a lot of things that resonate with me. And to be an artist is to respond to all of those things that resonate.”

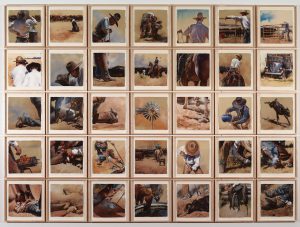

Branding Arrangement | Watercolor | 138 inches long | 2014

Matthews was born in New York City in 1949, and his family moved to San Francisco soon after. The city’s creative heritage shaped him, and he knew from a young age he wanted to be an artist. Matthews’ father ran an ad agency, and his mother was a fine artist who painted portraits and then transitioned to abstraction. She taught Matthews “how to see,” showing him to squint his eyes and render details into shapes, and she took him to museums as a child. So did his grandfather, Abbott Kimball, who would send his grandson sketches on scraps of paper from his travels to Brazil, India, Italy, Thailand, and elsewhere. This showed Matthews that he could travel the world, painting what he discovered along the way.

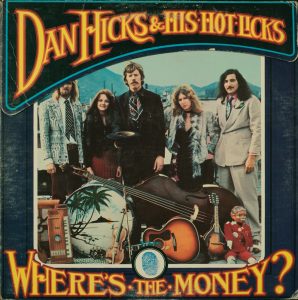

Album cover for Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks, 1971

In 1970, Matthews moved to Los Angeles, determined to create album covers for bands. He was 20 years old and lived in a basement apartment on Hollywood Boulevard. Matthews studied typography books and taught himself hand-lettering and photography. Without formal training or experience, he began knocking on doors, taking his portfolio of watercolors to record studios and asking for work.

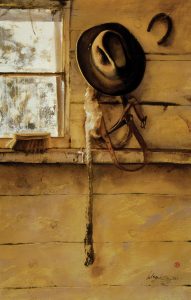

Cowboy Character | Watercolor | 28.5 x 18.5 inches | 2005

“I just didn’t have a clue what I was getting into. Not a clue. I didn’t know how to do it, what the art-business world was like, or the record business was like, and I just jumped in and kind of talked my way into a whole bunch of situations,” Matthews says, adding that eventually, Blue Thumb Records assigned him the live album cover for Dan Hicks & His Hot Licks. Since then, Matthews has designed some 140 albums and contributed to hundreds more. While in L.A., he also began creating posters for bands, events, and products.

Mrs. Schutte | Watercolor | 22 x 28 inches | 1992

In 1972, Matthews “had to get out of L.A.” and moved to Colorado in a wooden camper he built in Topanga Canyon. When he arrived, he lived in a teepee in Steamboat Springs for the summer and then moved to Denver and opened a studio.

He had his first art show in Denver when Dana Crawford asked him to create a series of paintings to hang in one of the Victorian buildings she had renovated in Larimer Square. Matthews created 54 paintings, adding typography to many of them. He also made a poster promoting his show and sold most of the work from his first exhibition.

But much like the cowboys that Matthews eventually became well-known for painting, he’s a restless spirit. In 1975, at age 25, the young artist longed to see the world. He left the U.S., banjo and portfolio in hand, with $1,000 in his pocket and the intention to be gone for five years. He traveled throughout Europe, painting Greek architecture and studying watercolors in British museums. He made a living playing banjo and painting portraits of houses.

March Flurries | Watercolor | 20.75 x 33.5 inches | 2004

In 1977, he ferried his VW bus across the channel to Ireland, drawn by the country’s rich folk music and his specific interest in learning the uilleann pipes. While exploring the traditional music scene there, he realized there weren’t many album-cover artists in Dublin, so he opened a studio in the uilleann pipers’ club. He stayed in Ireland until 1980, creating album covers for many of Ireland’s preeminent musicians.

When Matthews returned to the U.S., another chance encounter changed his life: Photographer Kurt Markus invited him to the first Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada. As Matthews writes in the retrospective’s catalogue, the Great Basin, with its “ocean of rugged mountains and rolling sagebrush plateaus cradling some of the most isolated ranches in America,” and the hardworking families that lived there became a creative well-spring. And he started painting cowboys.

Motor West | Mixed Media on Canvas | 84 inches long | 2016

“The people appeal to me, and I really like who they are,” Matthews says, adding that his cowboy subjects are not anonymous models but instead people he knows well and admires. “I have learned a huge amount from being around them and have great respect for them, and I try to make sure that great respect is evident in the paintings.”

By 1990, Matthews was a full-time fine artist in Denver and could paint any subject that fascinated him, from cowboys to Canyon de Chelly, European architecture to industrial Western buildings, Amish families, and Pittsburgh steelworkers. He also created public art, such as the 64-foot-long mural on the Dickies Arena in Fort Worth, Texas. Working with John Grant of Public Art Services and sculptor Buckeye Blake, the installation includes a glass-tile mosaic of wild horses framed by two bronze bas-relief sculptures.

Cipher Tie | Acrylic on Canvas | 84 inches long | 2016

During his life, Matthews trusted that his internal compass would land him in the right place at the right time. “I really live intuitively, and that has a huge amount to do with how I paint, how I decide on subjects, how I design paintings,” he says. This lends itself well to watercolor, and Matthews appreciates the medium’s flexibility in creating light washes and “big, thick, dark, woefully rich colors.”

“A big part of painting in watercolor is allowing it to run and create something that you didn’t necessarily intend, and that is something that I really like,” says Matthews. “It’s like riding a pony, and you know that pony is as much a part of the experience as you are. When I’m painting in watercolor, I know the material is a large part of what’s going to make the finished piece wonderful. So I give it rein, and I let it go places that I wouldn’t necessarily think of going.”

Elevator Status | Watercolor on Paper | 29.75 x 14 inches | 2012

It’s a landmark moment to stand in a museum, surrounded by your life’s work. Looking around the exhibit at Western Spirit and taking stock of what he’s created left Matthews feeling lucky and a little speechless. As an artist always following his intuition to new places, it’s a rare opportunity to look back.

“It’s just mind-boggling, because every poster, every album cover, every painting, every different project brought its own anxiety and stories and dynamics and bliss and frustration. Every one of these projects. And to see walls of them, it’s just mind-boggling.

“It’s very emotional, and it’s overwhelming to see all of this,” Matthews says. “And also, I’m still a young guy. I’m 74, but I still feel like I’ve got a good 20 years left in me. So I feel like, in a lot of ways, I feel like my best work is in front of me.”

No Comments