07 Jan Time’s Imprint on Nature

In the mid-1970s, Mark Klett was a young man with a degree in geology and an interest in photography when he heard about an intriguing United States Geological Survey (USGS) project. The agency was sending geologists to the West to take pictures from the exact vantage points where geographic surveyors in the 1860s had set up tripods and documented the landscape using heavy glass-plate cameras. The goal of these “repeat photographs,” the USGS explained, was to compare the historic and new photos to identify changes in geology.

Klett was fascinated by the idea. A few years later as a photography graduate student at State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo, he embarked on a similar venture. Klett and two other photographers received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to travel to more than 120 sites around the West to take pictures. Over three years, the trio stood in the virtual footprints of famous 1860s and ’70s photographers including William Henry Jackson.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, One Hundred and Five Years of Photographs and Seventeen Million Years of Landscapes; Panorama from Yavapai Point on the Grand Canyon Connecting Photographs by Ansel Adams, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and the Detroit Publishing Company, Digital Inkjet Print, 24 x 60 inches, 2007 | Left (two views): Ansel Adams, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1941, Courtesy of the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ | Middle view: Alvin Langdon Coburn, Bright Angel Canyon, ca. 1911, Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY | Right: Detroit Publishing Company, The Grand Canyon of Arizona Across from O’Neil Point, 1902, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

This time, however, the interest was not geological. As Klett puts it, “The landscape in places like the Grand Canyon or Yosemite doesn’t change that much in 100 years.” What did change was Klett’s way of thinking about the nature of time, culture, and landscape photography.

He recognized that photographers were not strictly documentarians. Instead, their work reflects the aesthetics and perspectives of the individual photographer and the larger culture — as well as the available technology — at a particular moment in time.

The result of Klett’s pursuit, Second View: The Rephotographic Survey Project, was published in 1984. A few years later, another young man interested in photography stumbled upon the book in his college library.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Details from the View at Point Sublime on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, Based on the Panoramic Drawing by William Holmes (1882), Digital Inkjet Print, 24 x 96 inches, 2007 | William Henry Holmes, Sheets XV, XVI, XVII. Panorama of Point Sublime | From Clarence Dutton, Atlas to Accompany the Monograph on the Tertiary History of the Grand Cañon District, 1882, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Byron Wolfe was working at the University of Redlands after graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in anthropology and evolutionary biology. He was researching graduate degrees in environmental studies but kept finding himself returning to the photography section. “I didn’t know about rephotography. I was instantly smitten,” he says. The concept brought together his passions for photography, the land, and discovering how societies evolve. In 1995, he entered Arizona State University (ASU) as a graduate photography student specifically to study under a certain professor — Mark Klett.

Klett quickly noted his student’s talent and saw that he and Wolfe had shared interests, including “rephotography,” a term Klett coined to distinguish his artistic approach from the USGS’s science-oriented objectives. He invited Wolfe to be part of a student-faculty rephotography project that culminated in the 2004 book, Third View, Second Sites: A Rephotographic Survey of the American West, which contained an interactive DVD designed by Wolfe.

Timothy O’Sullivan, Rock Formations, Pyramid Lake, Nevada | Silver Gelatin Photograph | 8 x 10 inches | 1867 Copy Print from the Collection of Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“Mark was experienced in the field and had a vast knowledge of the history of photography and a unique way of thinking and seeing,” Wolfe remembers. “A lot of that time I was just a sponge, taking in what he had to offer.”

Anne Wilkes Tucker, curator emerita at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, describes Klett as “remarkable in his generosity to students, colleagues, and others in the field.” In the 20 years since the Third View project began, Klett and Wolfe have worked together on multiple collaborative efforts as artistic, intellectual peers, and longtime friends. Among their books together are Yosemite in Time: Ice Ages, Tree Clocks, Ghost Rivers, in which they expanded their collaboration to include writer Rebecca Solnit; Reconstructing the View: The Grand Canyon Photographs of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe; and Drowned River: The Death and Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado, also with Solnit.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe for Third View, Pyramid Island from the Tufa Knobs, Pyramid Lake, Nevada | Silver Gelatin Photograph | 8 x 10 inches | 2000

Klett, who lives in Tempe, Arizona, is a Regents Professor of Art at ASU. Wolfe lives in Philadelphia and is a professor and program director of photography at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Both artists have received Guggenheim Foundation fellowships and a joint award from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and each has work in the permanent collections of dozens of museums in the U.S. and internationally. Best known for their collaborative rephotography, they also follow separate personal artistic paths, although with a remarkably similar driving interest in using the camera to think about place, time, and change.

“Mark’s personal work is diaristic, reflecting his presence and experience in the landscape. Byron, especially in his book Everyday: A Yearlong Photo Diary, focuses on the personal and family, also in a diaristic way,” says Rebecca Senf, chief curator at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography. Senf curated Klett and Wolfe’s Grand Canyon photography for a 2012 exhibition at the Phoenix Art Museum and has worked with Wolfe on other projects. She notes that the two men share a similar sense of humor and “both find the artmaking practice very joyful, even with its challenges.”

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Rock Formations on the Road to Lee’s Ferry, AZ, Digital Inkjet Print, 36 x 76 inches, 2008 | Left inset: William Bell, 1972, Plateau North of the Colorado River near the Paria, Courtesy National Archives | Right Inset: William Bell, 1972, Headlands North of the Colorado River, Courtesy National Archives

Growing up near Albany, New York, Klett’s first significant experience with photography was visiting a friend’s darkroom as a young teen. “I was just amazed,” he says of watching black and white photos emerge from the chemical baths. In college, he focused on science while taking pictures on the side, but when it came to graduate school, he was called to photography. “I went where my heart was,” he says. He earned a Master of Fine Arts from SUNY at Buffalo, in the school’s Visual Studies Workshop.

Wolfe, raised mostly in Tulsa, Oklahoma, remembers a pretty standard childhood but also with a strong interest in art. As a boy, he painted photo-realistically in watercolor photos from books and magazines until, at age 13, he decided to take pictures as references for his painting. As soon as he picked up a camera, he realized he enjoyed it at least as much as painting.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Above Lake Tenaya, Connecting Views from Edward Weston to Eadweard Muybridge, Digital Inkjet Print, 24 x 103 inches, 2002 | Left: Edward Weston, Juniper, 1936, courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona ©1981 Arizona Board of Regents | Right: Eadweard Muybridge, Ancient Glacier Channel, at Lake Tenaya, Mammoth Plate No. 47, 1872, courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

In their early days of rephotography, Klett and Wolfe used film rather than digital cameras. But they still had an advantage over the USGS rephotographers. In the mid-1970s, film was brought to a photo lab and developed — often hours from remote locations — before the team could see how closely their vantage point matched that of the earlier photographers. Wolfe and Klett used a large format camera with Polaroid film, allowing them to view small prints developed on the spot and adjust their vantage point as needed. By 2007, digital photography had caught up to the pair’s standards, with Wolfe leading their transition into digital technology.

Over the course of their work together, Klett and Wolfe have broadened their rephotographic approach. With the Yosemite project, the pair created a panoramic image of Tenaya Lake by combining their own photo with views by three renowned photographers from the past. In the process it became clear how much the earlier artists’ work reflected their personal inclinations and the worldview of the culture in which they lived. Eadweard Muybridge, shooting the lake in 1872, included a significant amount of foreground with dead trees and rocks, and a cluttered, chaotic feel. Edward Weston’s 1937 take was much more minimalist and modern; while Ansel Adams, circa 1942, presented the scene through a classic Romantic lens suggestive of the power of nature.

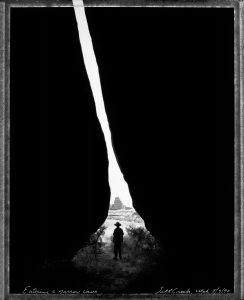

Mark Klett, Entering a Narrow Cave, Salt Creek, Utah 5/9/90 | Silver Gelatin Photograph | 20 x 16 inches | 1990

The differences speak not only of cultural aesthetics and ways of thinking about nature, but also the photographic equipment used: wide angle was popular in the 1870s, while longer lenses employed for the later images eliminated foreground clutter and produced a cleaner, more modern-feeling view.

- Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Receding Dead Pool and Signs of a Future River, Lake Powell | Digital Inkjet Print | 13 x 19 inches | 2012 (left) and 2014 (right)

As Senf points out, Klett and Wolfe’s work involves “an interesting synthesis of their experience of the place and knowledge that precedes these artworks.” Tucker adds that Klett and Wolfe together have “pushed the medium, reimagining basically how to make a straight photograph but incorporating within it more complex ideas.” She notes that while the pair “completely abandoned the one-click photo, their work is still documentary because it is of a time and place.”

For the Glen Canyon and Lake Powell project, Klett, Wolfe, and Solnit revisited the site of color photos taken by Eliot Porter in 1963, just before the canyon was flooded by the Glen Canyon Dam. Porter’s work was an elegy to a lost river and canyonlands. When Wolfe and Klett photographed it some 50 years later, climate change and drought had resulted in the re-emergence of land that had been underwater for decades.

Byron Wolfe, First Day: My Grandfather Died and I Turned Thirty-Five | Digital Inkjet Print | 6 x 8 inches | 2002

“What’s really compelling about this work is that when you look at an old photograph, you think it has nothing to do with you. And then you go there and realize you can relate to the earlier picture because you see how it is now, and suddenly history is not this thing in a box,” Klett says. For him, perceiving points in time and the relationship between them produces an almost startling awareness that all moments in history are equally as real and alive and important as the present one. “It was a visceral realization,” he says.

Byron Wolfe, Rainy Weather, Ravens at Dawn | Digital Inkjet Print | 6 x 8 inches | 2002

These days, Klett and Wolfe are adding to their artistic repertoire by exploring video, audio, stereoscopic photography, and 3D printing. “We’re experimenting with technology and ways of seeing. We riff like musicians and see where we can go,” Klett says. Indeed, early in his career Klett made a conscious decision to forego market pressures and take the riskier road in all his work. It’s a value he shares with Wolfe, and which fuels their conversations and collaborative practice. “We had an unspoken, and now spoken, rule: to reinvent what we do on a regular basis,” Wolfe says. “We’re always willing to follow each other’s lead.”

No Comments