24 Jul Triangular Visions

Since time immemorial, the number three has held significant meaning across the disciplines. The Rule of Three is used in art, architecture and design. We find the number three in children’s stories: The Three Little Pigs, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, The Three Billy Goats Gruff. From mythology to contemporary academics, the number three features prominently. Third time’s a charm. Three strikes and you’re out.

For the Namingha family in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the number three possesses a magic all its own: One father plus two sons equals three artists. The father, Dan Namingha, paints large canvases, filled to the edges with color. Oldest son, Arlo, creates bold sculptures in bronze, wood and stone. Youngest son, Michael, completes the trio of artists with compelling photography printed in digital inkjet images. Together, the three put forth remarkably diverse bodies of work that shed light on their Hopi-Tewa culture and life far beyond the boundaries of the pueblo.

One of the most celebrated Hopi-Tewa artists in the world, Dan Namingha’s art has traveled the globe, transcending Native-American art boundaries. Exhibiting at the Salon d’Automne, Grand Palais in Paris, France, Dan’s work has been shown in Chile, Cuba and a host of European countries.

In the United States, he has been honored with exhibits at museums ranging from the Board of Governor’s at the Federal Reserve and the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, among many others.

Dan comes from a family of creatives; his great-great-grandmother was the famous Nampeyo, a Hopi-Tewa potter whose works are touted alongside those of Maria Martinez as among the most important Native American ceramics of the 19th and 20th centuries. While Nampeyo’s tradition of pottery making is continuing through the generations, Dan Namingha’s family has chosen different media to express their artistic visions.

All through elementary school, Dan received kudos for his drawing and painting skills. During high school, he was awarded scholarships to study painting at the prestigious University of Kansas, and later at the Academy of Art in Chicago. He settled into his own expression of painting when he studied at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the 1970s. In 2009, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate Degree from the Institute of American Indian Arts in recognition of his achievements.

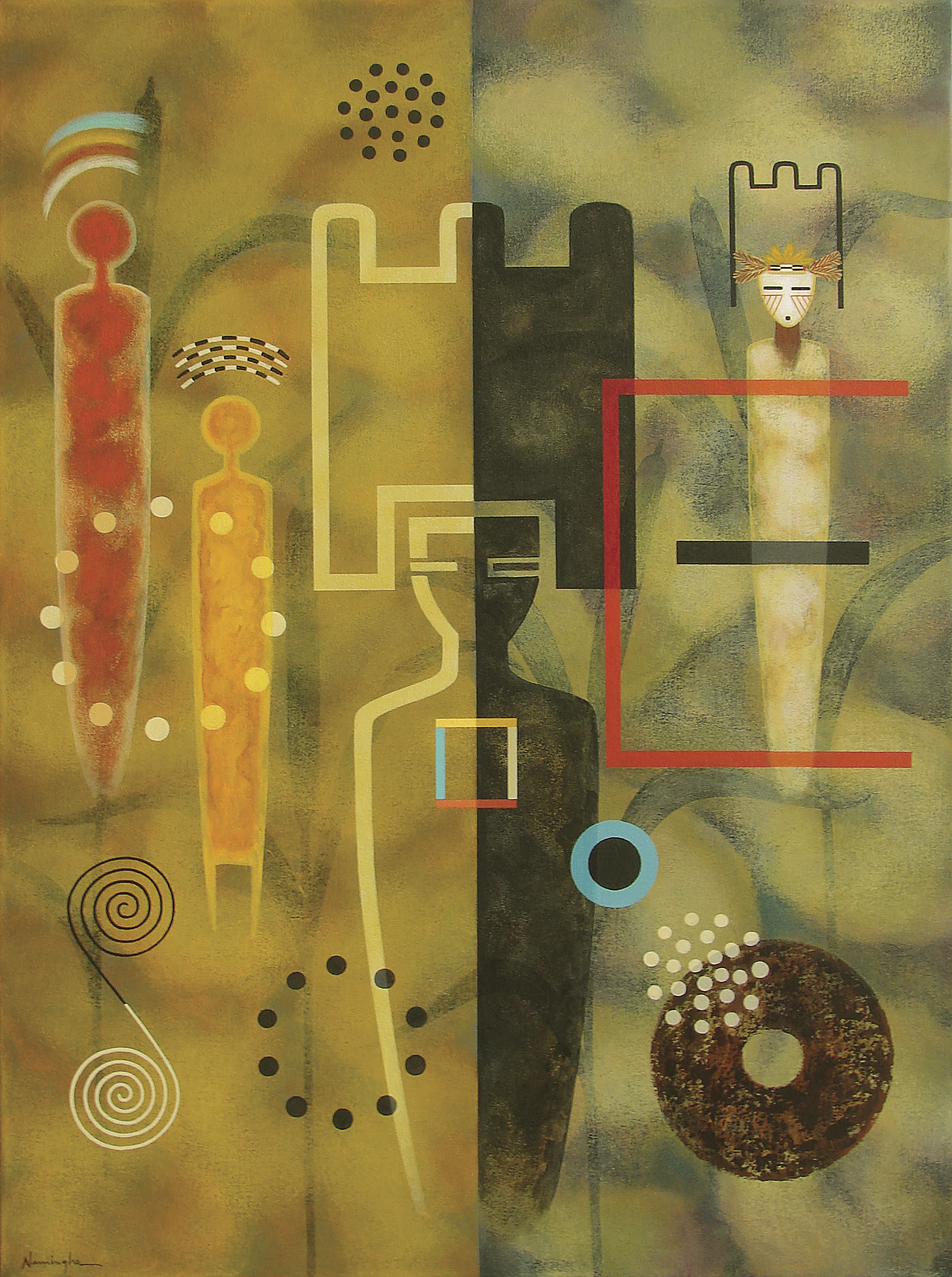

With vivid boldness, Dan paints landscapes to relate stories of his culture. He explains that some of his paintings might contain a reference to a song or a chant that is sung in ceremonies of the Hopi-Tewa people. “If you listen to the words of the song carefully, it tells a story. It’s done in such a poetic way that I immediately start getting this visual image in my head.” Thomas Hoving, former director of the Metropolitan Museum in New York wrote in The Art of Dan Namingha that Dan’s work is visual poetry.

While many of his uncles are carvers of the sacred ceremonial Kachina doll, Dan might paint a fragment of one onto his canvas. He explains why he uses fragments: “If someone goes to Hopi and is non-native and has never seen a ceremony, they are only getting a glimpse because they don’t understand what they are witnessing. It’s foreign to them.” Fragments, he says, gives them that same experience.

Arlo, 38, grew up in his father’s studio. “I taught both my sons the basics of art,” Dan says, “like how to prime a canvas.” All three laugh at the insider’s joke about cheap labor. The camaraderie that exists between the three is contagious and their creative energies seem to be always at work.

Traveling with his father to exhibits across the country, Arlo was amazed by the architecture he saw, particularly the first time he visited New York City. Raised on the Ohkay Owingheh Pueblo of New Mexico, where his mother, Frances, grew up, the big city seemed decidedly foreign and profoundly appealing. For a time he considered pursuing the study of architecture, but for Arlo, creating art was inherent.

Like his father, Arlo expresses himself as a Hopi-Tewa using his experiences in sacred ceremonies, revealing fragments of a Native American tradition. He’s not afraid to experiment with different materials: His early years were dominated by wood sculptures, but Arlo now works in clay and stone, and in fabricated and cast bronze.

Arlo’s work has been recognized with exhibits across the country. His art, while abstract, has a refined look. The Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Springs, California, acquired one of his works for its permanent collection and, in 2002, the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, New Jersey, acquired two pieces for its permanent collection.

Youngest son, Michael, 33, has the distinction of creating yet another form of art. Using digital inkjet technology on canvas and paper, his studio is categorically different than those of his father and brother.

Michael grew up in Santa Fe and, like his older brother, traveled with Dan to art shows in cities across America. Michael, too, was taken with the architecture he saw. He describes his first time in New York City as akin to being in a canyon; only this one was different from the ones he knew — compellingly different. Michael fell in love with New York City and chose to study at the venerable Parsons School of Design, thinking that design would be his way of expression.

Referred to as a pop artist and as an iconographic artist and photographer, when asked which one fits him best, Michael answers plainly: “All three — photographer of iconic pop culture.”

Unlike his father and brother, Michael’s art does not depict Native American culture. Rather his work incorporates pop culture and merges his experiences living in New York and Santa Fe. While traveling back and forth, living in both cities, something drew the artist back to his hometown. “I’d come back for a summer and that summer turned into five years. I’d forgotten what stars looked like. There was maybe one in New York City and it was on a billboard in Times Square,” he says with a laugh.

His artistic vision, talent and worldly perspective have been put to use in Santa Fe where Michael is the youngest Arts Commissioner the City of Santa Fe has ever had. On a recent day he read some 31 grant requests from various arts organizations. His connection is clear. “I love it. It has been a way to connect with the community.”

The three Naminghas are a trilogy that exists firmly planted in two worlds. They are bound to and inspired by their shared Native American culture … and they are celebrated by the much larger art world. Their participation earlier this year in the sophisticated L.A. Art Show reflected clearly where they came from, and where they are going.

The trio will put forth a spellbinding selection of work when the venerable Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, hosts an exhibit of the family’s art beginning February 25, 2012. Ann Marshall, curator says, “It means a great deal to the Heard to be able to show the work of this talented family. The heart of their art is the depth of feeling they have for their cultural heritage and their land. From that they move out with different approaches and different media. They find so many ways to talk about those things — that’s terribly exciting!”

Senior Contributing Editor Shari Morrison has been writing about art for more than 20 years. An avid traveler, she visits museums and galleries reporting on national and regional art happenings. As a poet, she is a member of The Live Poet’s Society, which celebrates its anniversary in 2011 with a 20-year anthology, just off the press.

- (L to R) Michael, Dan and Arlo Namingha, photo: Kate Russell

- “Desert Pictograph” | Dan Namingha, Acrylic on Canvas | 26 x 24 inches | 2011

- “Horizon #4” | Arlo Namingha, Texas limestone, blood wood, African mahogany and purple heart | 20 diameter x 4.75 inches | 2010

- “Butterfly” | Arlo Namingha, Bronze (edition of 6) | 24 x 20.5 x 6 inches | 2007

- “Land of Entrapment (Santa Fe Cliche Series)” | Michael Namingha, Inkjet on Paper | 33.25 x 24 inches | 2010

- “am i better than you?” | Michael Namingha, Inkjet on Canvas “26 x 40 inches | 2005

.png)

.png)

-18--570.png)

-for-Ad.png)

.png)

--A.png)

No Comments