04 Apr True Vision

THE LAST THING MICHAEL NARANJO remembers seeing was the man he shot.

On January 8, 1968, Naranjo was a 22-year-old draftee in Vietnam when his Army patrol was ambushed in a rice paddy.

“My friends were dying all around me,” he recalls.

Naranjo and the squad leader crawled into the jungle, the rest of the squad — those still alive — pinned down in the rice field while U.S. gun ships flew overhead. “We were the only ones in the jungle except for the Viet Cong,” he says.

That’s when he saw him, an enemy soldier sticking his head out of a foxhole, looking for someone to kill.

“Our eyes met briefly,” Naranjo says, “and I pulled the trigger.”

Moments later, a hand grenade grazed his hand. He turned toward it, trying to knock it away. The explosion lifted him up and set him on his knees.

“I thought I was going to die,” he says. “I heard my squad leader behind me asking me if I was OK, and I said, ‘Just get me out of here.’”

Naranjo was airlifted to a field hospital. When he woke up, both hands were tied down. He would have only limited use of his mangled right hand. And he was blind.

That could have been the end of this story. A promising career cut short. An Indian boy from New Mexico’s Santa Clara Pueblo, whose mother was a well-known potter, having his dreams of turning clay into sculptures become a casualty of war.

Instead, it was a new beginning. In a hospital in Japan, Naranjo found a piece of clay and tried to sculpt with his left hand.

“It was like coming across something you’ve been looking for,” he says. “Prior to that, I would be laying there, wondering what I was going to do with my life. When you’re a young man, your whole life is in front of you, and suddenly you can’t see any of it. My [right] arm was still tied down. They were doing skin grafts. I couldn’t get out of bed. So when I discovered I could still sculpt, I think it made the transition so much easier from suddenly having this horrendous disability to knowing that everything was going to be OK. Because now I had a purpose, and it was what I’d always wanted to do. And now I had all the time in the world to set about getting it done.”

Forty-five years later, Naranjo has certainly gotten it done.

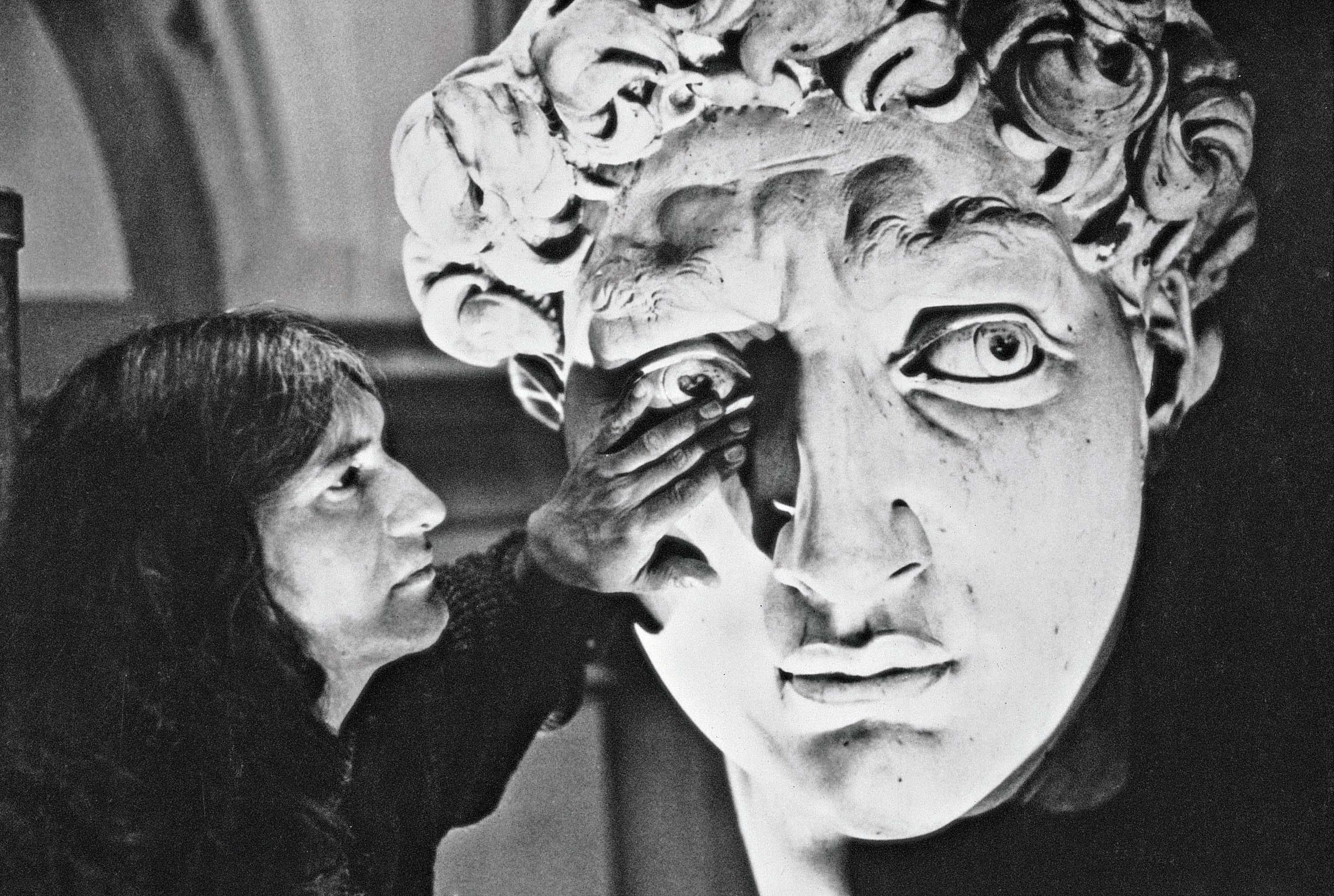

He has met presidents and Pope John Paul II, won countless honors and accolades — including the 2007 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts — has touched Michelangelo’s sculptures and has had shows across the globe. This year, Inner Vision, a book by his wife, Laurie, will be published, and in September, Nedra Matteucci Galleries in Santa Fe will host a retrospective of Naranjo’s career.

The unique show will feature 40 sculptures spanning Naranjo’s career, plus approximately 65 pieces, many of which have been sold out for years. Dubbed The Collection, the 65 pieces will be sold intact. “This important volume of work is the core and history of Michael Naranjo’s creative talent,” Matteucci says.

“Michael’s work gives people a sense of hope and healing,” says Shanan Campbell Wells, owner of Sorrel Sky Gallery in Durango, Colorado, which has carried Naranjo’s work for eight years. “Furthermore, his story helps us all to realize that anything is possible and that we can all follow our dreams. His work is so easy to talk about and to sell. It has such wide appeal.”

Much of Naranjo’s work comes from childhood memories. “As a kid, I really liked making those figures out of clay,” he says.

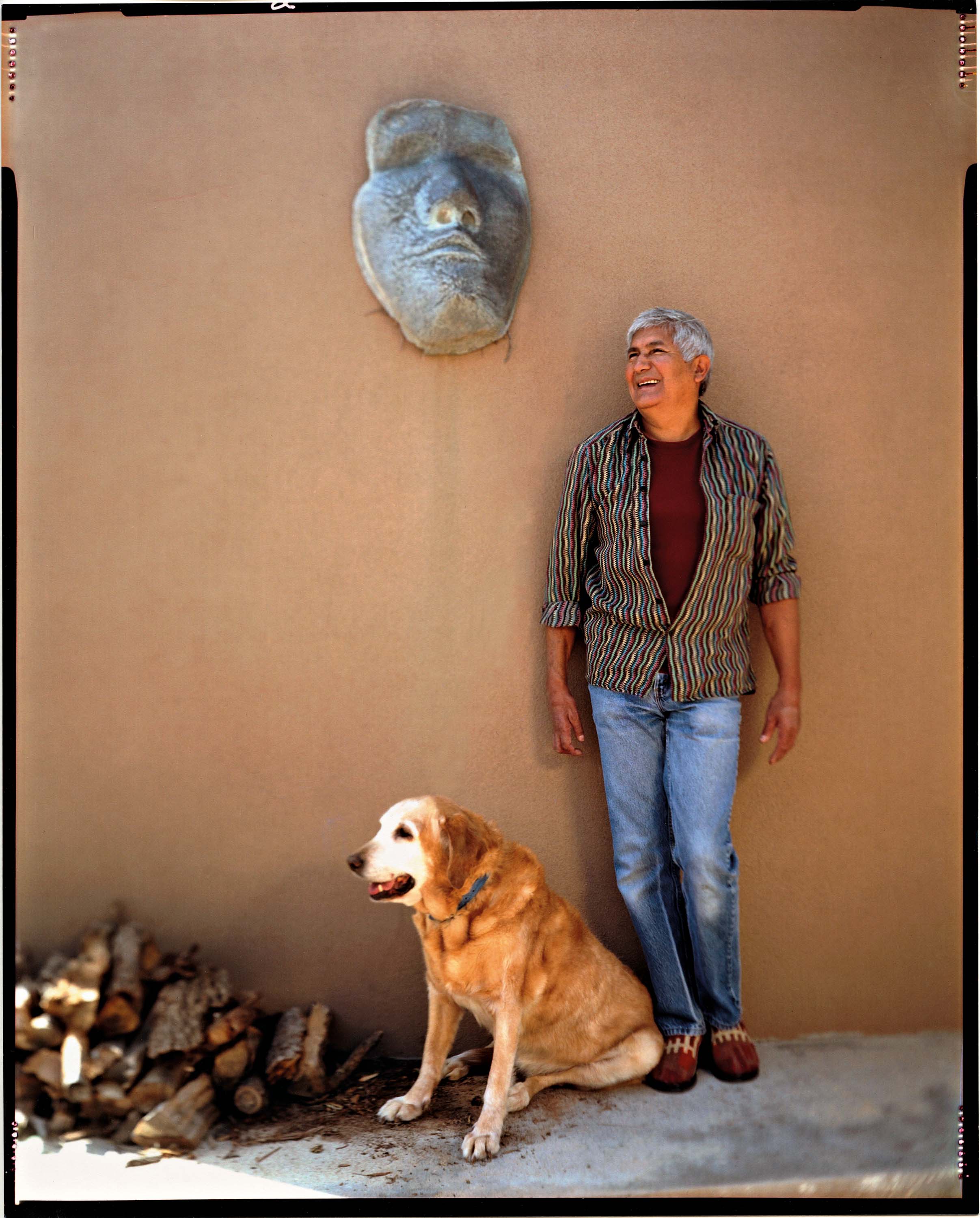

A soft-spoken, silver-haired man, he sits in his 800-square-foot studio behind his home in Albuquerque, where he and his wife moved from Santa Fe last summer. “I guess that’s where it began. What I saw out there in the woods and at Indian dances on Feast Days at our pueblo and other pueblos.”

Other ideas come from books, from dreams or talking to people. “You’ll hear a word, and that sets you off,” he says.

“Whether the subject is an eagle ready to take flight, a solemn Pueblo dancer or the timeless relationship between a mother and child in a life-size bronze fountain, Michael Naranjo enriches our understanding and experiences in life,” says Matteucci, who has represented Naranjo since 2002. “His work challenges us to see more deeply, yet it offers us solid footing in the familiar. We feel at peace and are gratified to appreciate the complete beauty of his sculpture.”

Naranjo traded the first piece he had cast in bronze to his sister for two pumpkin pies. “That was my first sale, I guess,” he says. “After that, I started getting into galleries, started selling pieces, having shows here and there, started entering juried competitions. I guess I was on my way.”

Yet human nature often brought about skeptics.

“People would often ask, ‘Who helps you?’ And when I said, ‘No one. I did it all myself,’ there would be that pause, that questioning feeling of never quite believing you. They, of course, would ask, ‘How much can you see?’ I say, ‘I can’t see.’ They’d say, ‘Can’t you see light?’ I say, ‘No. I don’t have any eyes. I have prostheses for eyes.’ They say, ‘Can’t you see shadows?’ I say, ‘No, I don’t have any eyes. Day and night are the same.’ When I go into my studio and close the door, they still think I can open my eyes and see, or something to that effect. Some people just didn’t want to believe.”

Says Wells: “When I see a new piece by Michael, I instantly get a vision of him sculpting it, using his hands as his eyes.”

Indeed, that is how he sees, by touch and feel and memories. He often works on several figures at once, setting some aside and coming back to them after a few days, weeks, sometimes years.

“When I’m making it, I see what it’s going to be,” he says, while massaging pieces on a wax work-in-progress of an eagle dancer. “But before I can put the wings and headpiece and tail feathers on, I have to make the man.”

It’s a painstaking process for any artist.

“Working with wax, I’ll sometimes forget to stop when my fingers are getting tender or I’ll get a callus or blister, so then, of course, I can’t see anymore because my eyes are these fingers. So what I have to do is take a nice thick emery board and file down the calluses to be able to keep going.”

When he was first starting out, he would work 18- to 23-hour days until, exhausted, a piece was finished. Now, he has been forced to slow down. Leaking spinal fluid has left him with headaches, sometimes debilitating, since 1994. Last July, he had rotator-cuff surgery, and he had just returned to work on a limited schedule last fall.

Yet you won’t hear him complain. About anything.

“Long ago, I discovered that if I was offered eyes, I wouldn’t take them. What for? I have my work, and I have a wonderful wife and two beautiful daughters and I’m happy. What more can anyone can ask for?”

- “In Disguise” | Bronze | 8 x 18 x 8 inches

- Naranjo uses his fingers to “see” Michael Angelo’s “David.”

- Naranjo stands beside his “best friend.”

- “Little Cloud” | Bronze | 92.5 x 18 x 18 inches

- “Eagle Man” | Bronze | 86.5 x 63 x 46 inches

- “Golden Vision” | Bronze | 20 x 8 x 10 inches

- “Eagle’s Song” | Bronze | 11 x 22 x 10 inches

No Comments