10 Mar Turning 30 with Andy Warhol

ON MAY 17, 2017, the National Museum of Wildlife Art, located in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, will open an exhibition of Andy Warhol’s Endangered Species prints to kick off its 30th anniversary celebration. Despite boasting a diverse collection of some 5,000 works of wildlife art, there’s nothing like a Warhol show to generate buzz and bring in an audience.

Warhol’s group of 10 silkscreens owe their origin to a conversation between the artist and the art dealers Ronald and Frayda Feldman, his main print publishers, according to the museum. Allegedly, the Feldmans spoke to Warhol about current ecological issues and suggested they collaborate on a portfolio of endangered species prints to bring attention to the environment’s plight, specifically in regard to beach erosion.

While all of this sounded noble, both parties also quickly grasped the financial potential of the project. Warhol and Ronald Feldman had a long history of collaboration, including on the Ads, Myths and Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century portfolios — all of these projects were conceived with the marketplace in mind.

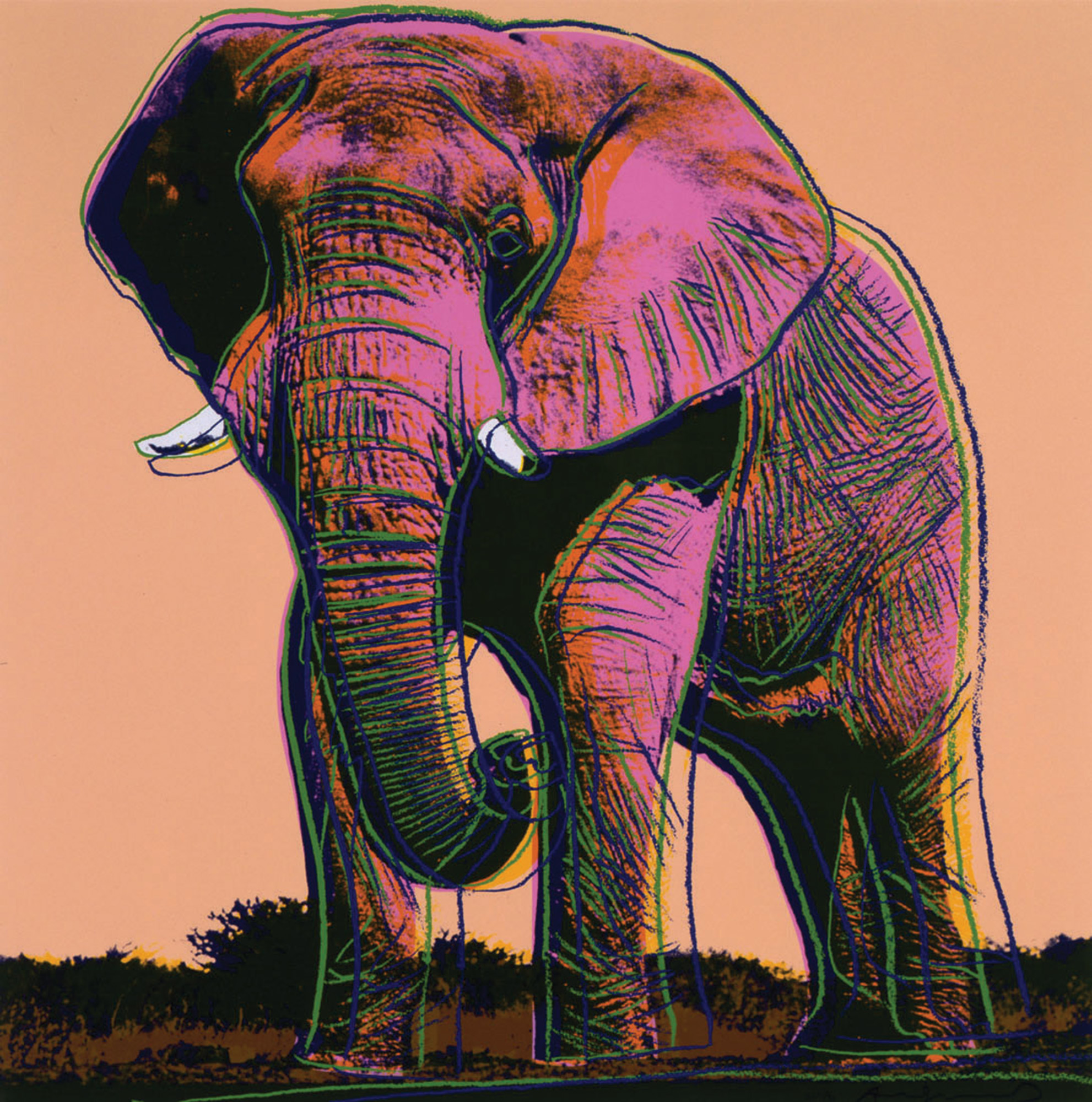

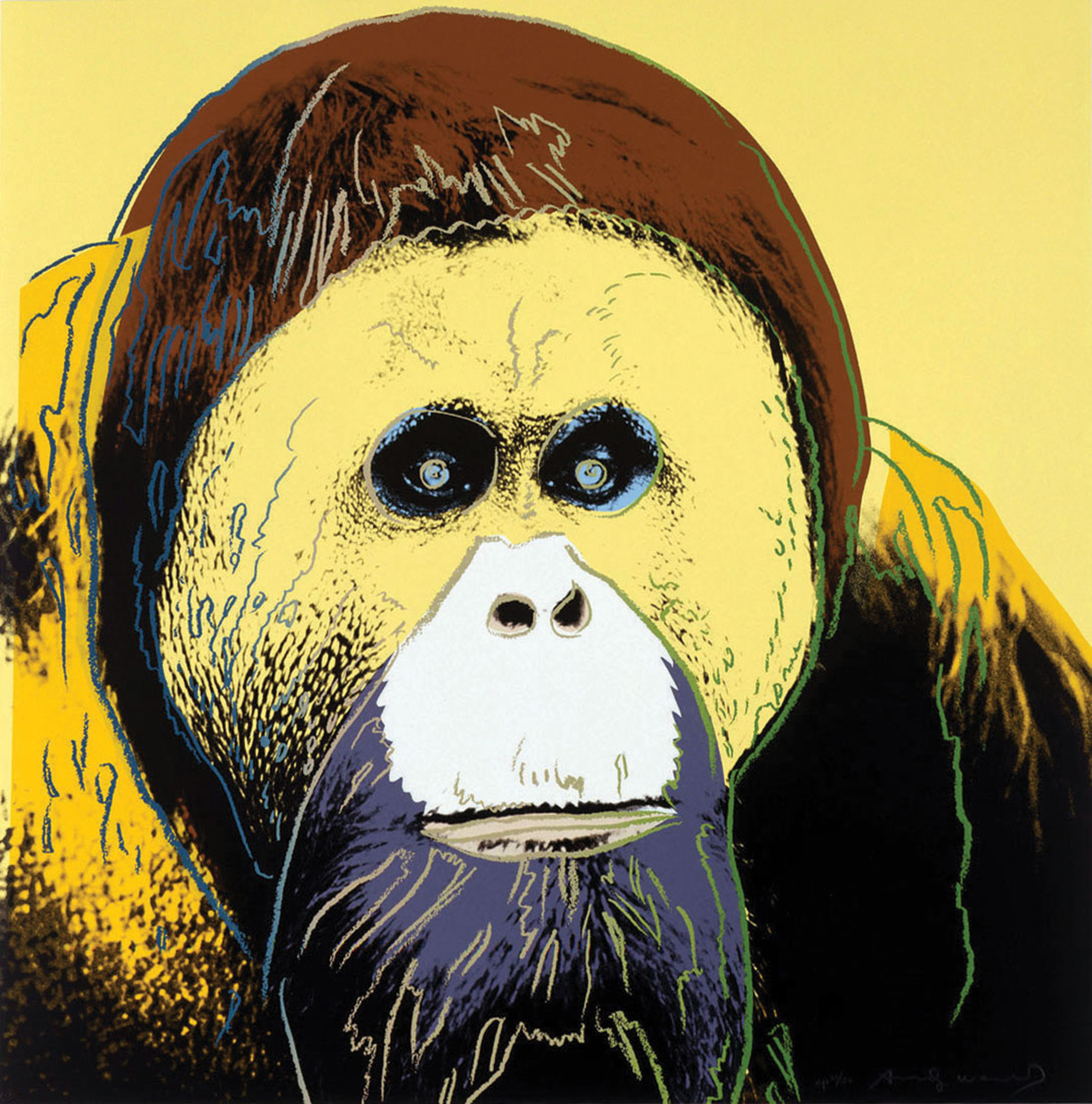

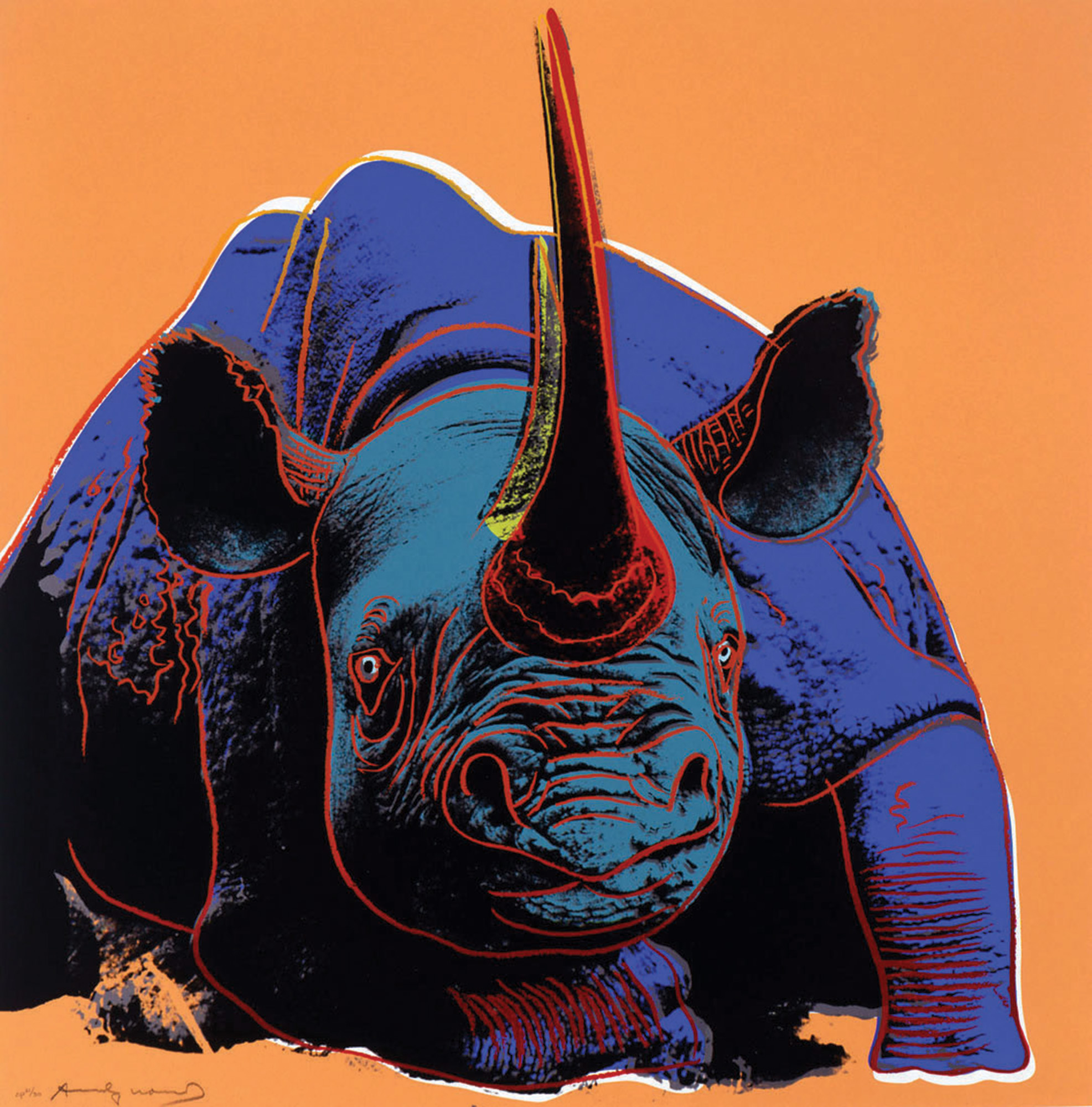

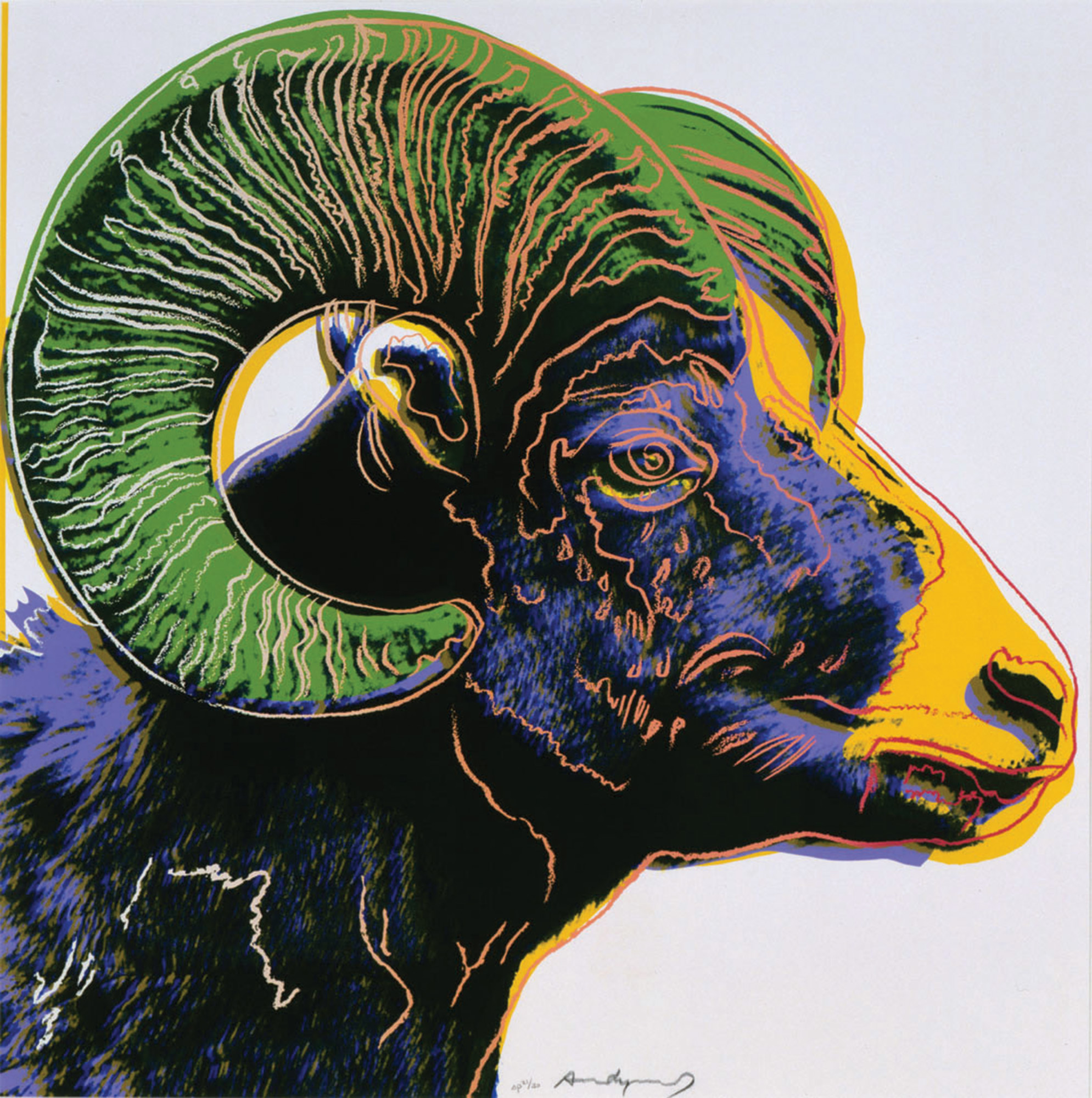

But — surprise — unlike the lukewarm reception the above projects received, the Endangered Species portfolio was an aesthetic and critical hit. The vibrantly colored screen prints, produced in 1983, were described as “animals in make-up” by Warhol, according to Christie’s Auction House. There was something fresh and visually provocative about seeing a Siberian tiger rendered in vibrant Pop colors, reinforcing the notion that Warhol was an underrated colorist. The prints looked so good, it made one wonder why more Pop artists didn’t incorporate wildlife imagery into their classic 1960s work. With the exception of Mel Ramos, who paired his cheesecake female nudes next to everything from a Kodiak bear to an ocelot, most of his colleagues steered clear of the subject.

Warhol’s Endangered Species portfolio features 10 animals, among them a tree frog, an African elephant and a butterfly. The screen prints highlight animals from the endangered species list enacted only a decade before. The 150 editions are augmented by a corresponding group of 10 canvases, which were exhibited at New York’s prestigious Van de Weghe gallery in 2014.

Sadly, most of the creatures illustrated by Warhol remain on the endangered species list and the majority of the group has seen its population decline. The exceptions are the bald eagle, whose numbers have increased in recent years, and the Pine Barrens tree frog was listed as “near threatened” in 1996. China’s recent decision to ban the importation of ivory by the end of 2017 has sparked hope for the elephant’s survival.

Upon the release of the Warhol Endangered Species portfolio, a number of our country’s leading natural history museums, including the American Museum of Natural History, exhibited the series. In the Andy Warhol Diaries, the artist humorously recalled attending their opening reception in his honor, “There was a crowd in front of the museum when we got there, and I thought it was for me, but they were filming a Disney movie.”

In addition, other institutions, such as the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, began selling complete portfolios to their wealthy members as fundraisers. The initial release price for the 10 serigraphs hovered between $25,000 to $35,000 — which was considered reasonable for the times. Today, an Endangered Species set, in mint condition, would bring approximately $500,000 at auction (though in 2015, Heritage Auction House in Dallas sold a set for $725,000). In 2016, the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction’s annual sale featured a unique color-trial proof of Bighorn Ram, which soared to $71,400, more than doubling its presale estimate.

As for how the National Wildlife Museum came to own their Warhols, Dr. Adam Harris, the Petersen Curator of Art and Research, explains, “In 2006, we borrowed a set of the Endangered Species prints from the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. The prints received such a positive response that we found a way — through a number of fundraising events — to acquire a set of our own. What’s really nice is that we were able to buy an entire portfolio where the edition numbers match.”

The National Museum of Wildlife Art is the only art institution in America (and possibly the world) dedicated to the planet’s incredible diversity of living creatures. Even more impressive, the collection boasts animal-related imagery that spans 4,500 years, from 2,500 B.C. to the present. It includes works by such major historical figures as Georgia O’Keeffe, John James Audubon and Carl Rungius. The museum also houses first-rate paintings by contemporary artists, including Tom Uttech, who peppers his uncanny landscapes with so many birds you think you are watching Hitchcock’s “The Birds.”

As the National Museum of Wildlife Art moves into its fourth decade, it has begun to gradually expand its collection to include artists from around the world. The museum’s curators are also open-minded enough to consider acquiring pictures that are clearly on the edgy side. Currently, they’re hoping to add a work by the street artist Keith Haring to their holdings — if they ever find one that depicts a coyote.

Given the museum’s close proximity to Grand Teton National Park, it attracts a diverse group of visitors hoping to round out their Wyoming experience. “Our biggest audience comes from California, followed by New York,” says Jennifer Marshall Weydeveld, director of marketing, “but we also receive plenty of visitors from Wyoming.”

As for the museum’s 30th anniversary, Harris plans to reinstall pieces from the museum’s permanent collection and host celebratory art shows and events throughout the year. As he succinctly puts it, “We’re planning to hang some old favorites and what we hope will become new favorites.”

In addition, the museum intends to yoke its Warhol show to an exhibition by National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore. What should make the show especially meaningful is that Sartore documents animals in captivity, often depicting vanishing species. “Sartore wants to call our attention to the peril they’re in,” Harris says.

One can easily imagine the connection between a Joel Sartore color photograph of an exceedingly rare white rhino, juxtaposed with an Andy Warhol serigraph of the almost equally scarce black rhino, creating a poignant experience for the viewer.

- “Curl-crested araçari (Pteroglossus beauharnaesii),” (detail) Dallas World Aquarium Texas | Photos: National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore

- “Fennec Fox (Vulpes zerda),” (detail) St. Louis Zoo, Missouri | Photos: National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- “A luna moth (Actias luna),” Lincoln Children’s Zoo, Nebraska | Photos: National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore

- “Varied capuchin (Cebus versicolor),” Summit Municipal Park in Gamboa, Panama | Photos: National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- Andy Warhol [1928–1987], “Endangered Species Portfolio” | Screenprint | 38 x 38 inches | 1983 | Gift of the 2006 Collectors Circle, an anonymous donor and the NMWA Acquisitions Fund, National Museum of Wildlife Art ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York/Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

- The National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson, Wyoming. Photo: courtesy of NMWA

No Comments