30 May Turning Straw into Gold

GOLD, THE FIRST METAL WIDELY KNOWN TO OUR SPECIES, has long been associated with gods and immortality. But in New Mexico during the 1700s, intricate leafing and gold facings were absent from most places of worship. The gleaming precious metal was a rare commodity and not easily transported. The use of gold was strictly controlled, and artisans had to find other materials and art forms with which to decorate and adorn their local churches.

“People had no access to ebony and gold, but they wanted to imitate the gilded crosses of Spain,” master artist and traditional encrusted straw expert, Jimmy Trujillo, explains. Straw appliqué offered an alternative to expensive inlay and became “poor man’s gilding” for all of the crosses and retablos in the high desert.

The contrast between dark painted or soot-stained wood and the tiny golden fibers of straw and corn husks applied in delicate designs emulates the ebony, gold leafing and Old World traditions of marquetry. European marquetry is a term that applies to two different types of wood surface decoration — inlay and veneer. Straw appliqué (and the traditional variant encrusted straw) is a simplified adaptation combining both styles. Decorative fragments cover a portion of the surface like inlay, but are adhered to the planar surface with a resin varnish similar to veneer.

Because of the fragile nature of the art form, there are few historic pieces in existence and little is known about straw art’s history. Most santeros (Spanish devotional artists) agree that the technique came to the New World via the Moors who had invaded Spain and learned the fine woodworking skill. Although both marquetry and the use of straw in art are found in many cultures across the globe, encrusted straw crosses are unique to southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

The intricate and unique relics all but vanished by the early 20th century. “Resin isn’t a durable material, and the pieces are easily damaged. In the 1850s the railroad started bringing in pewter and plaster crosses. It was out with the old and in with the new. There was no foresight to keep any of the straw art for collections. It was all burned or buried,” explains Trujillo.

The entire tradition was essentially saved in the 1930s by a handful of visionaries. At the time, the W.P.A. Federal Arts Project was trying to combat high unemployment while pushing to revive local practices in a move to counter the slow disappearance of regional folk art. “There was a whole movement across the United States to save America’s past — its folk art,” explains Tay Marianna Nunn, the director and chief curator of the visual arts program at the National Hispanic Cultural Center. “The revival period was a post industrial reaction.”

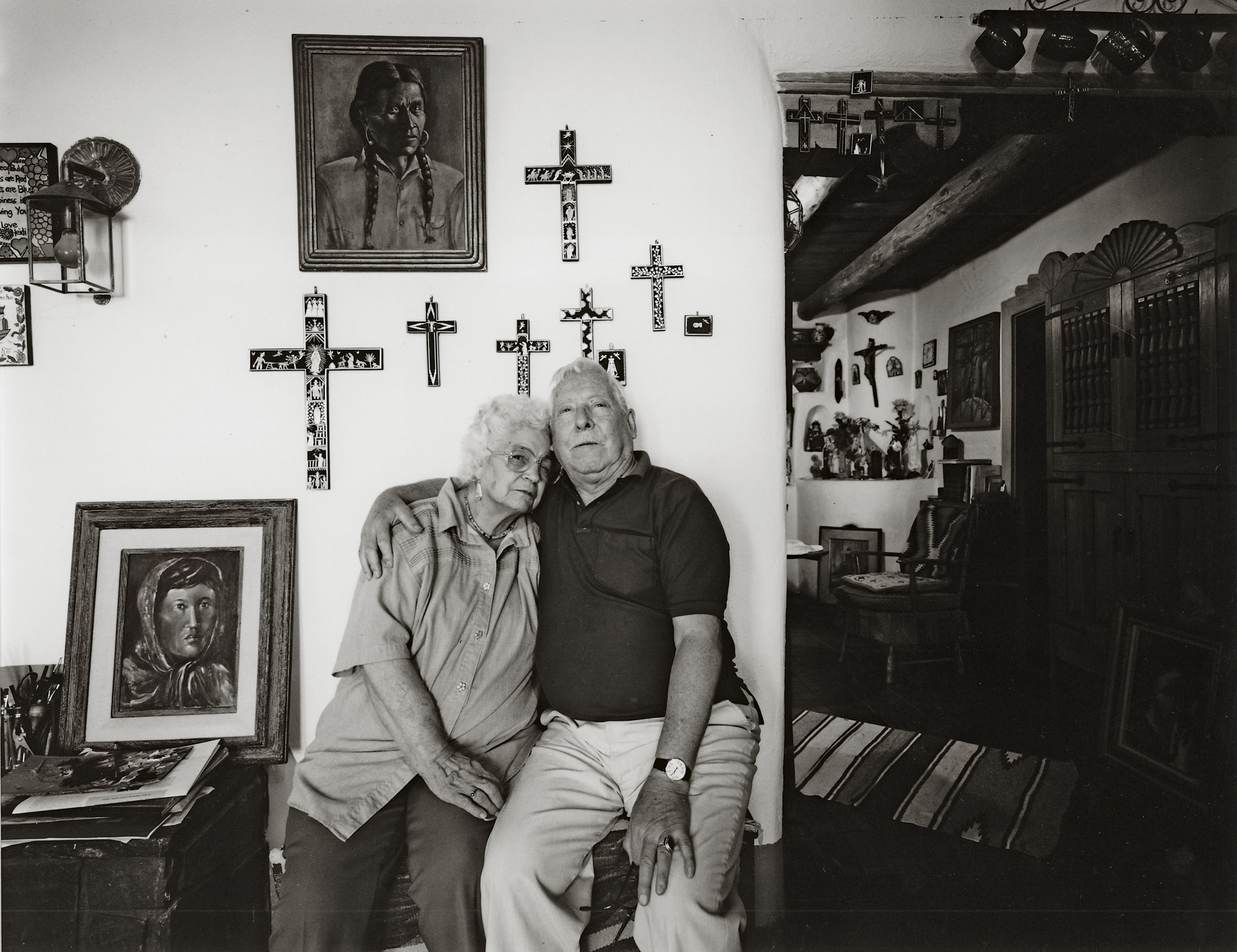

The W.P.A. and, more specifically, painter Russell Vernon Hunter in New Mexico, encouraged Eliseo Rodriguez to try working with straw. Eliseo, the first Spanish-American painter at the Santa Fe Art School, and his wife, Paula, worked to resurrect the lost encrusted-straw crosses and art, but by the 1950s they were the only practitioners of the medium. “What was so extraordinary about Eliseo’s contribution was that he really transformed the art and moved it forward,” Nunn says. “Because he was a trained painter, he didn’t mimic patterns. He painted with straw and that hadn’t been done before in the colonial tradition.”

In the 1970s, the couple’s work was discovered by a conservator at the Museum of International Folk Art who encouraged them to show their pieces at the Spanish Market in Santa Fe. Since then, their work has been collected by the Smithsonian and other prestigious museums, and they were given a Lifetime Achievement award by the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, as well as a Lifetime Honor in 2004 by The National Endowment for the Arts.

Eliseo and Paula Rodriguez gained widespread exposure and have since been teaching others the art, including many family members. Their son, Aguinaldo Rodriguez, grew up around these artistic endeavors, but only recently began working with the medium himself. “I was always support for my parents. I would help set up the shows and get wood. I hadn’t been able to do it myself until now because of the time,” he says. “It’s work, and it takes a lot of effort and time. It’s almost like a job, but I don’t mind doing it.” Since Aguinaldo started two years ago making straw appliqué like his parents, he has sold everything he’s made. “I’m encouraged by the fact that people like my work. It’s a bonus to my teaching salary,” he says.

Like the Rodriguez family, Jimmy Trujillo is passionate about passing on his extensive knowledge. “I have several students who are now in the Spanish Market. I don’t want the straw art work to die out again, so I’ve been teaching as many people as are willing to learn.”

Trujillo was dabbling in this and that when famed santero, Dr. Charles Carrillo, married his niece. Carrillo continuously brought articles and made suggestions for his artistic path, insisting that being a santero was in his family blood. Trujillo loved to carve, but avoided painting. His work was always small and intricate, but nothing really resonated with him until Carrillo showed him an article about gesso relief. “It wasn’t so much the article, but a small photograph in it of a straw appliqué cross. I responded immediately to the tiny pieces of straw, and even though I had always worked in miniature, I saw how I would be able to create larger pieces and still stay small,” Trujillo says.

Today, Trujillo is known as the person who revived the original techniques of encrusted straw. “I started with Elmer’s glue, but I’m a super traditionalist so I started researching how the medium was originally done. There was very little written about it. All I could find was a paragraph saying that a combination of soot and resin was used, but it didn’t work. I figured out that the soot was on the resin, not in it. Soot from the candles used in prayer would build up on the crosses, and when they would wipe them clean, it would adhere in the cracks. Sometimes the santeros would use soot to color the wood beneath.” Trujillo has been compiling research since 1984 and hopes to someday document his findings and rare historic pieces in a book.

Today only a precious few artists work in straw, and it is only because of the commitment of the Rodriguez family, Trujillo and a handful of others passing on their knowledge that the art form is still vibrant and sought after. The Spanish Market in Santa Fe, a principal outlet for colonial folk art, hosts most of the registered artists and even includes a youth category. “It [straw appliqué] has been one of the categories at Spanish Market that has really gone great guns,” Nunn explains. “In 2005 a single piece by Martha Varoz Ewing won five prizes at the show. It was a pivotal moment for straw.” For the first time in nearly a century, the future looks golden for this small niche of the art world.

WA&A Senior Contributing Editor Audrey Hall’s portraits and essays about architecture, style and travel are featured in numerous publications including Western Interiors and Design, Big Sky Journal and Mountain Living.

- Golden rods of straw are cut and patterned against dark-stained wood in straw appliqué

- “Esta Vida di Porti” 21 x 11 x .5 inches Jimmy Trujillo

- “Untitled”, 23.5 x 19 x 6 inches, Jimmy Trujillo.

- “Cross, History of Christ”, Santa Fe, NM 1978, Eliseo Rodriguez, Straw Appliqué. Courtesy of the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, Collections of the Spanish Colonial Arts Society, Inc., Santa Fe, NM (1979.011)

- A contemporary and noted artist, Jimmy Trujillo is one of the few people actively working in the traditional method of encrusted straw. Trujillo works at his studio in the Desert Southwest.

- “Hay Hijo de mi corazon”, 22 x 12.5 x .5 inches, Jimmy Trujillo.

No Comments