11 Jul Turning West

Throughout his 20s, Thomas Kegler toiled over his canvases, completing five or six a year, reinventing the wheel each time, yet never achieving what he felt was “beautiful art.” Then an accident nearly severed his drawing arm, and that changed everything.

Fifteen years and another life-altering loss later, he is one of the top painters of Contemporary Realism in America and is a living leader of the Hudson River School style, according to Beacon Fine Arts Gallery director David Griswold. This doesn’t mean he sticks to the academic realism espoused by the Hudson River masters, but that the training he received from the school frees him to move between realistic renderings and expressive interpretive pictures where light and boundaries are played with, brushstrokes evaporate, and mood takes hold.

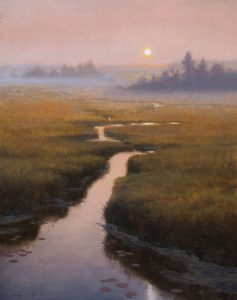

Moon Glow, Proverbs 1:5 | Oil | 12 x 9 inches | 2022

“I feel like the Hudson River School opened my eyes to [the] beauty in a dead leaf,” said Kegler. “I could literally walk out of my door right now and find a painting.”

If the painting he found outside his door turned out like others in his landscape portfolio, it would be infused with intense but quiet allure, rich in tone, spatial depth, and mystical, even luminous, light. In Light of Dawn, Psalms 119:76, a marsh stream meanders to the horizon where a rising sun casts pink light on the world. The details of grass and algae in the foreground are vivid, but the distant low fog and trees soften, giving way to feeling.

The Dawning, John 14:27 | Oil | 24 x 36 inches | 2021

“He’s got that underlying passion that delivers immense intensity in his use of color and light,” said artist Robert Pillsbury, president emeritus of the Salmagundi Club, where Kegler is a five-time exhibitor in the club’s American Masters show. “And there is this willingness to go all the way out to the end of where you could possibly go and take all the risks you could possibly take and come back with a masterpiece.”

Light of Dawn, Psalms 119:76 | Oil | 24 x 18 inches | 2016

Kegler’s renderings of Niagara Falls would be one such example of risk-taking. Though Frederic Church’s picture of the falls is famous, Kegler had a strong connection with the renowned cascade — having grown up in East Aurora, New York — and visited them in childhood. His remedy was to choose a different vantage point and hour of the day from Church’s work. It was three years from the time he began the paintings to finishing them, 15 in all. The largest of the canvases, Niagara, Psalms 84:11, is an 8-foot-wide panorama of Horseshoe Falls and is currently on exhibit at Niagara University’s Castellani Art Museum.

If beauty is as slow and patient as philosophers claim, Kegler’s evolution as an artist could be an object lesson. His masterly ability to render the characteristics of place in a way that evokes feelings of stillness and appreciation of nature converged after years of study, practice, debilitating injury, and heartbreaking loss.

The Lower Falls, Proverbs 16:3 | Oil | 72 x 48 inches | 2021

When his hand slipped and sent the blade of a chainsaw halfway through his right forearm, he used the trauma to re-commit to painting. Already in his mid-30s, he told himself, “I’m actually going to teach myself how to paint.” He bought books — many from the 19th century — and read up on processes he’d taken for granted or never learned. “All these lightbulbs were going off, like ‘Oh, that’s how you physically construct a painting,’” he says. The self-schooling was enough to get him into a juried Hudson River School Fellowship, organized by Jacob Collins.

In the field from sunrise to sunset, learning from geologists, botanists, and meteorologists what was actually happening in the landscape and sky, gave Kegler the language to orchestrate the theatrical composition of a painting. He could set a meadow under a full moon or at daybreak when the atmosphere is transitioning and vibrant. He could employ scumbling to effect other kinds of emotional experiences — a technique used by Tonalist George Inness, who is arguably Kegler’s strongest influence.

Morning Coffee, 1 Peter 1:13 | Oil on Linen | 12 x 9 inches | 2022

Kegler’s life and art-making were altered again in 2017 when his wife Kimberly died, leaving him with their two children to raise alone. A year spent walking with her through treatments, and then losing her, made him determined to say something in his work — to put the spotlight on God. Now, every canvas he finishes has a scripture reference in its title, invitations, he says, for viewers to explore the connection between the natural world and the Divine. “Sometimes it’s quite literal; sometimes I try to leave it, make it more open-ended, so the viewer can find their own association.”

And he’s slowed down some, too, both for practical purposes — he’s a single dad and full-time high school art teacher — and because he’s more intent on achieving a powerful picture than he is with hitting a benchmark. He wants to create works that evoke a response similar to the one he had when he encountered his first George Innes, Home of the Heron. “It’s a very quiet painting, but it was like whoooo, like an [intake] of breath.”

The Storm Has Passed, 2 Corinthians 4:17-18 | Oil | 18 x 48 inches | 2022

Kegler has also expanded his geographic palette. While the lush and forested terrain of Upstate New York has never withheld material, a trip to Yellowstone National Park in 2020 offered fresh inspiration and a new point of connection with his Hudson River forebears, including Church and Thomas Moran, whose trips West rewarded them with unimaginable kinds of light and geologic drama, and kept them creatively inspired, at least in Moran’s case, for the rest of their careers.

The expansiveness of Yellowstone and Wyoming was humbling to Kegler in a good way, and he quickly fell in love with the grandeur. This September, for the second year in a row, he will participate in the annual Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale. Kathy Thompson, the show’s director, said Kegler’s paintings of Yellowstone Canyon and the Lower Falls last year earned him an immediate fan base. “His work is so outstanding, you can’t just walk by,” Thompson says. Indeed, Kegler confirmed that his Western market was opening up.

For this year’s show, he’s working on moonscapes of a mountain ridge south of Cody, and a famous protrusion called Castle Rock. If the nocturnes in his portfolio are any indication, they are bound to pull you into a vision that is both realistic and otherworldly, one that you won’t want to turn from.

“I feel like he’s got this inner calling that is different from what I see in other artists,” said Pillsbury. “It’s not driven by commercialism; it’s not driven by success; it’s just ‘this is what I’m going to do, and I’m sticking to it.’”

No Comments