24 Jul Unplugged and Unleashed

WE BELIEVE WE KNOW AN ARTIST BY THE TWANG IN THE VOICE, the 10-gallon hat on the head and the works based on things that are familiar.

Sculptor T.D. Kelsey and painter Julie Oriet have earned praise for their authentic regional interpretations of the American West, in scenes of ranch life and rodeo, portrayals of wildlife and sketches of rural people inhabiting pastoral settings. Most artists, after all, do assert their greatest prowess in translating the places they know closest to home.

But in Kelsey’s and Oriet’s case, it is a debatable premise being put to a wonderful test. At the Simpson-Gallagher Gallery in Cody, Wyoming, a tandem exhibition, Unplugged and Unleashed, that features both artists this fall, rolls out a trove of bronzes, watercolors, pastels and journal entries inspired by years of quiet international travel to exotic destinations. It’s safe to say that seldom in recent years, if ever, has there been another gallery event like it.

Nearly a decade in the massing, Kelsey is featuring dozens of new sculptures and Oriet as many paintings in a variety of media. “No cowboys or Indians,” Kelsey, whose work has been heralded in comparison to Charlie Russell and Frederic Remington, says. “Nothing North American.”

According to collectors of both artists who are flying into Cody for the occasion, the show is generating a buzz at a time when the art market itself is in flux.

The annual fall exhibition at Simpson Gallagher has become a special pre-interlude in the run-up to Cody’s Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale September 25 and 26, sponsored by the Cody Chamber of Commerce and hosted by the Buffalo Bill Historical Center’s world-renowned Whitney Gallery of Western Art where Kelsey is the featured artist for 2009. Last year, Simpson Gallagher hosted a major retrospective for landscape painter T. Allen Lawson. Pieces from that event were acquired by major museums.

“For me, it’s very exciting,” says Susan Simpson Gallagher, owner of the gallery that bears her name on Sheridan Avenue in downtown Cody, across the street from the famous Irma Hotel designed by William F. Cody, a.k.a. Buffalo Bill.

It is fitting that Kelsey is being feted as featured artist. Not long ago, the Whitney Gallery became the official repository of the Sidni A. Kelsey Collection, an amassing of 166 first-cast Kelsey bronzes set aside in memory of his late wife, who had visited fine-art museums around the world but counted the Buffalo Bill Historical Center as her favorite.

Part of Simpson Gallagher’s inspiration for the event comes from a visit she took long ago to the Woolaroc Museum near Bartlesville, Oklahoma — a venue in which fine art is interwoven amongst a folksy tapestry of objects innate to the culture of the West. “It creates a provocative juxtaposition for thinking about art,” she says. “Art isn’t a category separate from the human experience; it is an expression of the richness of it, and I think the experiences T.D. and Julie have had will transport the viewer.”

The gallery itself is being visually transformed to include trinkets, artifacts and other objects the artists have gathered on journeys extending across Mediterranean Europe, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania, the Central African Republic, Ethiopia and into the bazaar of Marrakech.

“I can’t wait for people to see the other side of T.D.’s work. Like his Western pieces, those inspired by Africa have tremendous impact,” says Mahlon Wallace III, a longtime Kelsey collector from St. Louis.

Kelsey’s sculpture takes on a different kind of dramatic flair from his figurative maquettes and monuments of cowboys and herd bulls often conveying the narrative of classic predicament scenes. For him, regular trips to Africa, which he’s been taking over a couple of decades, have been liberating artistic experiences, he says. A departure from his tighter Realism synonymous with his work on this continent, his interpretations of African predator-and-prey scenes are far looser and influenced by the 19th century European animaliers.

Kelsey recently was commissioned to create a series of bronzes featuring African animals for the St. Louis Zoo, following the popularity of a larger-than-life-sized monument of a Cape Buffalo titled Daga Boys.

Simpson Gallagher draws a parallel between Kelsey and a famous American writer who also had a fondness for the West, but whose work assumed greater texture and gravitas only after travels took him to Europe and deepest Africa.

“Kelsey’s work is reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway’s best writing,” Simpson Gallagher says. “The knowledge of his subject is unquestionable. They both experienced their subjects. They both have the ability to pare things all down to essential elements without sacrificing any of the depth and complexities. But most importantly, they are both artists who live with uncompromising passion.”

What sets Kelsey’s and Oriet’s work apart is integrity, she explains, noting that neither of the artists bears any airs or artificial affectations that get in the way of their absorption of information.

In Oriet’s case, Simpson Gallagher and Ken Schuster, chief curator of the Bradford Brinton Memorial & Museum in Big Horn, Wyoming, say her work, within the past decade, has assumed a level of artistic maturity and sophistication normally associated with the masters. In particular, her portraits of Maasai villagers, market scenes in Morocco and the melding of gentrified countryside with Moorish and Renaissance architecture in Spain and Italy, are evolved. In 2002, Oriet won the artist’s choice award at the Buffalo Bill show for a work titled Foothill Fantasy.

“I have been a longtime follower of Julie’s work going back to when she was a member of the Cody Country Art League,” Simpson Gallagher says. “She had done these marvelous watercolors in Italy and pastels of the West with a terrific atmospheric quality. And then I went to the C.M. Russell Show in Great Falls and encountered not only T.D.’s African faunal subjects but a series of portraits Julie had done that she called Dressed Up.”

Dressed Up were exquisite portrayals of African women with rich black skin, wonderful beaded necklaces and sarongs. “She wasn’t trying to put a face she knew onto faces she saw,” Simpson Gallagher notes. “Those were the faces of timelessness and they stopped me in my tracks.” Some of these pieces, which Oriet kept for herself, will be at the show.

Great friends, and in an odd bit of coincidence, Kelsey (b. 1946) and Oriet (b. 1958) were raised on small farm-ranches outside of Bozeman, Montana.

Besides his background as a rough-stock rodeo athlete and roper, another aspect of Kelsey’s enigmatic background is his tenure as a former commercial airplane pilot and his continued penchant for both collecting aircraft and flying them competitively.

“I know nothing about planes, nor what it feels like to control the skies, but I suspect that flight or flying informs his work,” Simpson Gallagher says. “It is the great adventure. Yet there is another element to his flying, the quality of solitude that fits T.D., the observer alone at peace with himself in a world that seems both fascinating and strange.”

When Kelsey isn’t traveling, he spends winter months at a ranch in west Texas, training cutting horses and tending to the endless tasks of keeping a spread in working condition — sculpting early in the morning before dawn and after sunset. Summers, however, he comes home and lives up the South Fork west of Cody near the wilderness of the Shoshone National Forest and Yellowstone National Park.

Oriet, meanwhile, has an old settler’s homestead northeast of Cody within a viewshed that drains into the mystical shadowlands of the Clark Fork of the Yellowstone River. Pronghorn and mule deer are frequent visitors, set beneath big skies passing overhead.

“Julie Oriet has not gotten anywhere near the recognition she deserves, but that is coming as more discover her work,” Schuster says. “She is at a point in her life where she is comfortable with who she is and where she’s at and it most forcefully is manifested in her art. Along with T.D., she has gotten boxed into what is known as the ‘Western art’ genre and not only is it simplistic, but it’s misleading.”

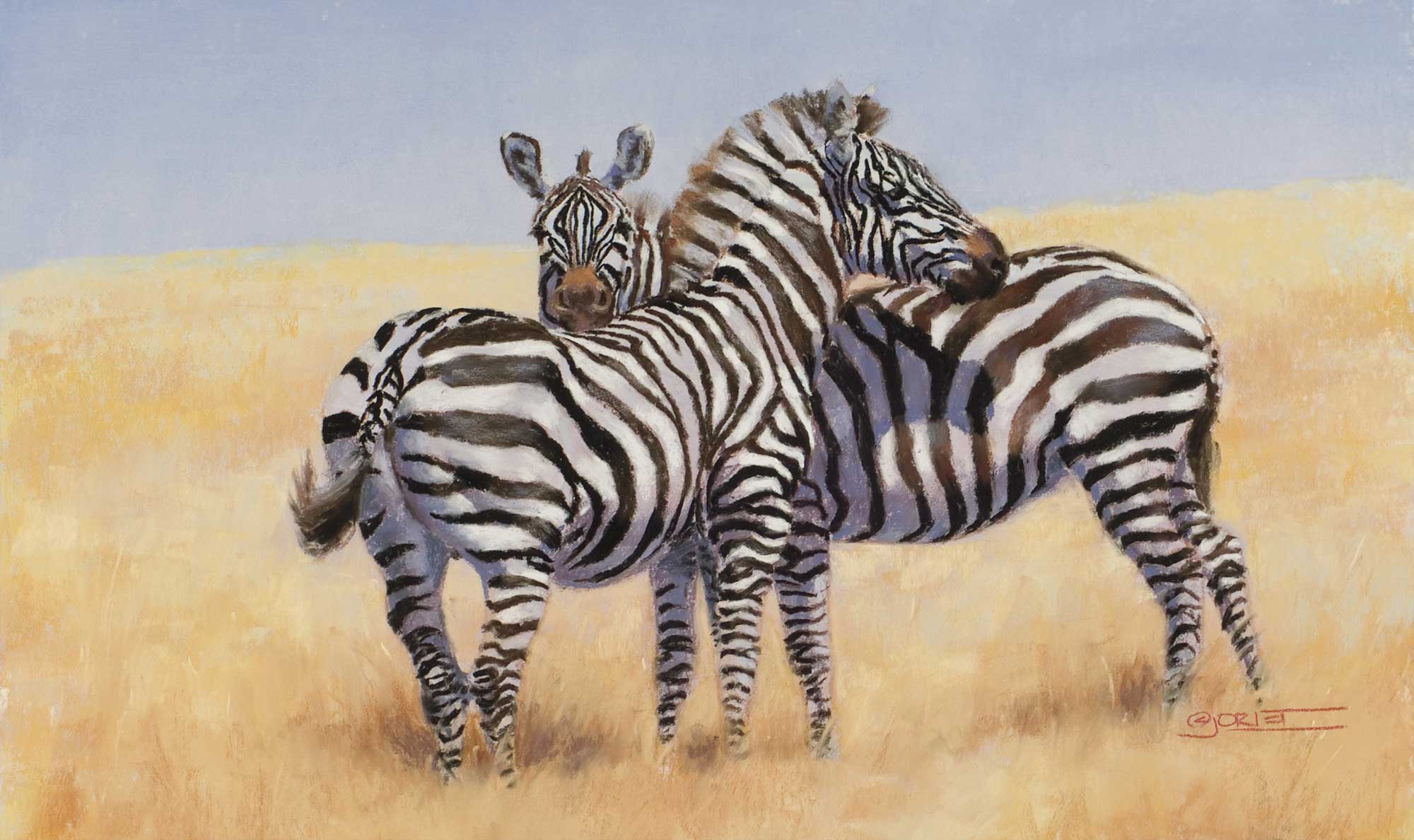

“What I appreciate most is the uniqueness of different places. There is nothing out there so boring that it can’t be painted,” Oriet says, sharing tales of sunsets on the vast plains of Africa with herds of zebra moving in fluid form past surreal groves of acacia. “Travel makes the mind expand,” she adds. “It makes you see your home turf in new ways, bigger than before.”

Journalist Todd Wilkinson has been writing about the environment and culture of the West for nearly 25 years. He is author of a forthcoming book about Ted Turner and a contributor to several magazines. He lives in Bozeman, Montana.

- T.D. Kelsey | “Field Trip” | Bronze | 5 x 26 x 10 inches

- Julie Oriet | “Samburu Camel Trek” | Pastel | 20 x 30.5 inches

- T.D. Kelsey | “Giant Among Giants” | Bronze | 6 x 22 x 20 inches

- T.D. Kelsey | “Bale King” | Bronze | 10 x 17 x 22 inches

- T.D. Kelsey | “Maasai Moran” | Bronze | 6 x 22 x 20 inches

- Julie Oriet | “I Got Your Back” | Pastel | 9.5 x 16 inches

- T.D. Kelsey | “Shula” | Bronze | 10 x 12 x 19 inches

- Julie Oriet | “Dressed Up (Maasai)” | Pastel | 21 x 18 inches

- Julie Oriet | “Old Man (Aboriginal)” | Pastel | 10.5 x 13 inches

.jpg)

No Comments