09 Jun Wall Drug: A Love story

“MAKO SICA,” OR “BAD LAND,” is what the Lakota people called the desolate buttes and geological formations in southwestern South Dakota. Water is hard to find and travel is difficult. Early peoples of the area hunted bison that lived on the plains and prairies. Officially designated a national monument in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Badlands became a national park in 1978.

This gigantic 244,300-acre parkland was laid down 30 million years ago, part of a saltwater sea pushed up by volcanic activity. Millions of years ago the creatures that roamed the area, once the water drained away, died and were covered with volcanic ash. Rivers sculpted the deposits, and geologic turmoil and erosion formed the land. The lower flood plain of the White River is prairie, the upper prairie great and grassy with flowing hills. Between the two is a “Wall.” It is a physical barrier preventing travel north and south between grasslands. The “Wall” runs one-half- to 3-miles wide. “Mako sica,” where travel was perilous to all but the hardy.

Ted and Dorothy Hustead were hardy enough to move to the town named for that “Wall” in South Dakota, in December 1931, with their 4-year-old son, Billy. Ted was a graduate pharmacist from Nebraska. He’d had his fill working for others and set out to find a pharmacy of his own.

It was inauspicious, but the town of Wall had a doctor, a bank and, most important for the devout Husteads, a Catholic church. It was also smack in the throes of the Great Depression. South Dakota was plagued with drought and grasshoppers. Crops failed, banks failed and the little pharmacy the Husteads bought on Main Street in Wall, population 300, wasn’t doing well at all.

The Husteads lived behind the store. They had three electric bulbs and power for the soda fountain from the town garage owner’s generator. It was so bad that Billy was afraid that if the store went out of business they’d put him up for adoption.

About this time, Dorothy suggested they put a sign out on the Interstate. Wall is 50 miles east of Rapid City and at the edge of the Black Hills, and just north of the Badlands. Night and day, the Husteads listened to the noise of cars driving past on US Highways 14-16, only a block-and-a-half away. The thing was, nobody stopped in the little town of Wall. Dorothy got the idea to offer travelers free ice water. Ted got a high-school kid to put a sign up on the highway. That did it. Weary travelers stopped, got a glass of free ice water and made the 24-by-60-foot storefront pharmacy popular. More signs brought more customers and, eventually, expansion into what has become one of the most popular roadside attractions in the world.

Each summer, approximately 20,000 people per day visit Wall Drug. There is a 530-seat restaurant, a roaring dinosaur, fine boot shop, bookstore and most everything anyone could want, from hair coloring to homemade fudge. The Husteads spend $200,000 to $300,000 annually for some 300- plus billboard signs that continue to proclaim: “Free ice water,” “Coffee 5 cents” and “Famous Western Art Gallery — A Wall Drug Must See.”

Wall Drug’s collection includes 320 original oil paintings by some of the most celebrated artists of the Golden Age of Illustration. Two original oil paintings of his mother and father by Gutzon Borglum grace the main dining room. They were painted by the Mount Rushmore sculptor when he was just 21 years old.

“The first painting was an Andrew Standing Soldier,” Ted Hustead said. Ted, Bill’s son and the grandson of founder, Ted Hustead, is now president of Wall Drug. “He depicted Native Americans as cowboys,” he said, trailing off into another story about another painting. Every painting has a story.

“Three … four years ago a guy called. He said, ‘I got an Andrew Standing Soldier.’ I asked him how much? He said $250. I told him to send it. It came packed in a hotel towel.

It’s worth $2,000,” says Ted.

Hustead’s stories often take detours and he spouts art history, rapid fire, as he discusses the collection. Hustead was offered two Dean Cornwell paintings by American Illustrator’s Gallery: The Train Station and The Man You Plan to Hang, the latter of which is an illustration from a book entitled The Enchanted Hill, by Peter B. Kyne.

The asking prices, Hustead recalls, were $330,000 for The Train Station and $130,000 for the The Man You Plan to Hang. “Three years later I got ‘em both for $170,000,” Hustead beams.

Considered the Dean of American Illustrators, Cornwell studied under South Dakota legend, Harvey Dunn.

“I just bought a Harvey Dunn for $175,000,” he admits, bringing the number of Wall Drug’s original Harvey Dunn oil paintings to 10.

Though Ted rattles off facts and figures with an insider’s savvy, his father, Bill, had no formal schooling in art or art history. Bill bought affordable Western scenes that he liked and began the collection to decorate the walls of the expanding business. “There was a time when illustration art was viewed as impure commercial art when compared to the nobler motivation in fine arts,” Wall Drug’s café menu proclaims.

Hustead was offered two Dean Cornwell paintings by American Illustrator’s Gallery: The Train Station and The Man You Plan to Hang, the latter of which is an illustration from a book entitled The Enchanted Hill, by Peter B. Kyne The asking prices, Hustead recalls, were $330,000 for The Train Station and $130,000 for the The Man You Plan to Hang. “Three years later I got ‘em both for $170,000,” Hustead beams.

Considered the Dean of American Illustrators, Cornwell studied under South Dakota legend, Harvey Dunn.

“I just bought a Harvey Dunn for $175,000,” he admits, bringing the number of Wall Drug’s original Harvey Dunn oil paintings to 10.

“I bought the N.C. Wyeth at auction for $46,000; it was appraised for $225,000 in 2010. The collection is valued at about $3 million today,” says Hustead. In addition to Dunn, Cornwell and Wyeth, the Wall Drug collection includes work by such heavy hitters as Benton and Matt Clark, Herbert Morton Stoops, Harold von Schmidt, Will James, Frank McCarthy and Gerald Farm.

Judy Goffman Cutler, museum director and co-founder of the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, looks beyond the economic value of the collection to its cultural significance: “Ted Hustead’s Wall Drug art collection brought a wealth of culture to South Dakota, where there is nothing of comparison for hundreds of miles. These artworks reflect the history

When asked about the Wall Drug collection, Hustead and general manager, Mike Huether, shared their reflections:

WA&A: What’s the theme of the Wall Drug collection?

Ted Hustead: I think the overriding theme is this … I’m a political science and economics major, not an art major. My dad and granddad were pharmacists. You buy what you like. What my dad did was buy illustration art before illustration art caught on.

Mike Huether: Basically the paintings told a story. We had a culture that developed great artists to illustrate books and short stories in magazines.

T.H.: In America it started with the father of illustration, Howard Pyle [1853–1911]. He built his studies from his experience in war. Pyle taught N.C. Wyeth, Dunn, Schoonover and other illustration artists. N.C. Wyeth painted 3,000 paintings; he had Andrew and Andrew had Jamie. My parents had the chance to buy a Jamie Wyeth painting of a Newfoundland dog for $30,000. They didn’t buy it. It could be worth $2 to $3 million now. Getting back to my theme … These great illustrators depicted America’s culture. There was a demand by magazines and for paperback book covers. Artists of the time had great teachers. Pyle and Dunn didn’t charge their students. They all worked together.

It was a farm system to produce great artists. These artists represent the greatest artists of our time. It was the Golden Age from 1880 to 1980. Remington and Russell were illustrators. Illustrations show the evolution of American culture.

WA&A: How do you merge your passion for Western art and business?

T.H.: We’re running a business here, not a museum. If we are not a successful business, we won’t have an art collection. We do a $12-million-a-year business and employ 100 local people and 120 college students in summer. We have about 2 million people visit us every year. … We want to improve our collection and get works by artists we don’t have. People come back because of the heritage of the place.

It was and is a family business.

We don’t try to exaggerate what we are. We are a roadside attraction. We get more people than the Badlands National Park.

WA&A: Tell us something we can’t know by looking at the works.

T.H.: Frank McCarthy was one of the best Western illustrators into the 21st century. He recently passed away. Dad had one of McCarthy’s paintings put away; it was unsigned. He packed it up and sent it to the artist and asked him to sign it. He signed it, sent it back with a note that said, “Bill don’t send me any more.”

WA&A: What do you love most about the collection? T.H.: We have the best private collection of Western illustration art … that can be viewed by the public for free, right here in the store. Our collection took off when Dad started expanding the dining room in the 1970s. He wanted it to be an art gallery dining room. I love sharing our collection with visitors.

WA&A: What are some of your goals?

T.H.: Dad was a visionary, way ahead of his time. Sure enough, 30 years later these paintings became masterpieces. They tell a story. Then I came along. I bought some of the best illustrations on the market. I wanted some of the best artists. Even buying the N.C. Wyeth was a stretch for us; let alone [the] Dean Cornwells and the big Harvey Dunn. My dad was more frugal. … It’s a family decision when you’re spending all that money on art that will not bring in any revenue. We really look forward to someone that comes in here and makes a comment like, “I can’t believe this. All these originals.” When the N.C. Wyeth came up at the Illustration House auction, Walt Reed, one of the owners, told me I should bid on it. I told him, “You have it down for $60,000.” Walt Reed said, “If you can get it for $60,000, it is a steal.” I couldn’t be there for the auction, couldn’t even be on the phone much. My son had a wrestling tournament. I said to Walt, “OK, I’ll go $60.” The hammer price was $46,000.

It is clear that Hustead’s passion for the art matches his desire to share it with people. He can look anywhere, in any room and talk about an artist’s inspiration or process. “There is so much to Andrew Standing Soldier’s work. He would go to junk yards and get mason boards to paint on. The board has a pattern to it,” he says, walking up close. “The art is all around. People can touch it.”

“They get ketchup on it,” Mike interrupted.

Hustead can laugh, but is undeterred. For as long as it is within his control, Wall Drug will be as much a tribute to Western art and the talented souls who told the story of the United States, as it is to the creativity, hard work and determination of his family in the face of obstacles.

“We expose people to our country’s heritage. It is wonderful to come to a public place with no admission fee and see a work of art valued at a quarter-million dollars. It is right there in front of them. Some argue that the art is near the fat-fryer, in front of the ice-cream stand. That people can rub against it. Where else can people see ’em? We take great pride in sharing our Western art collection with masses of people,” Hustead smiled, justly proud of his family’s role at amassing and preserving this remarkable collection for the benefit and enjoyment of so many.

- The Wall Drug art collection, which hangs on the hardwood paneled walls of the dining room and throughout the establishment, is valued at approximately $3 million.

- Herbert Morton | “Stoops Pocohantos Saves the Life of Captain John Smith” | Oil | 39 x 35 inches

- Keith Avery | “The Branding Oil” | 23 x 35 inches | 1982

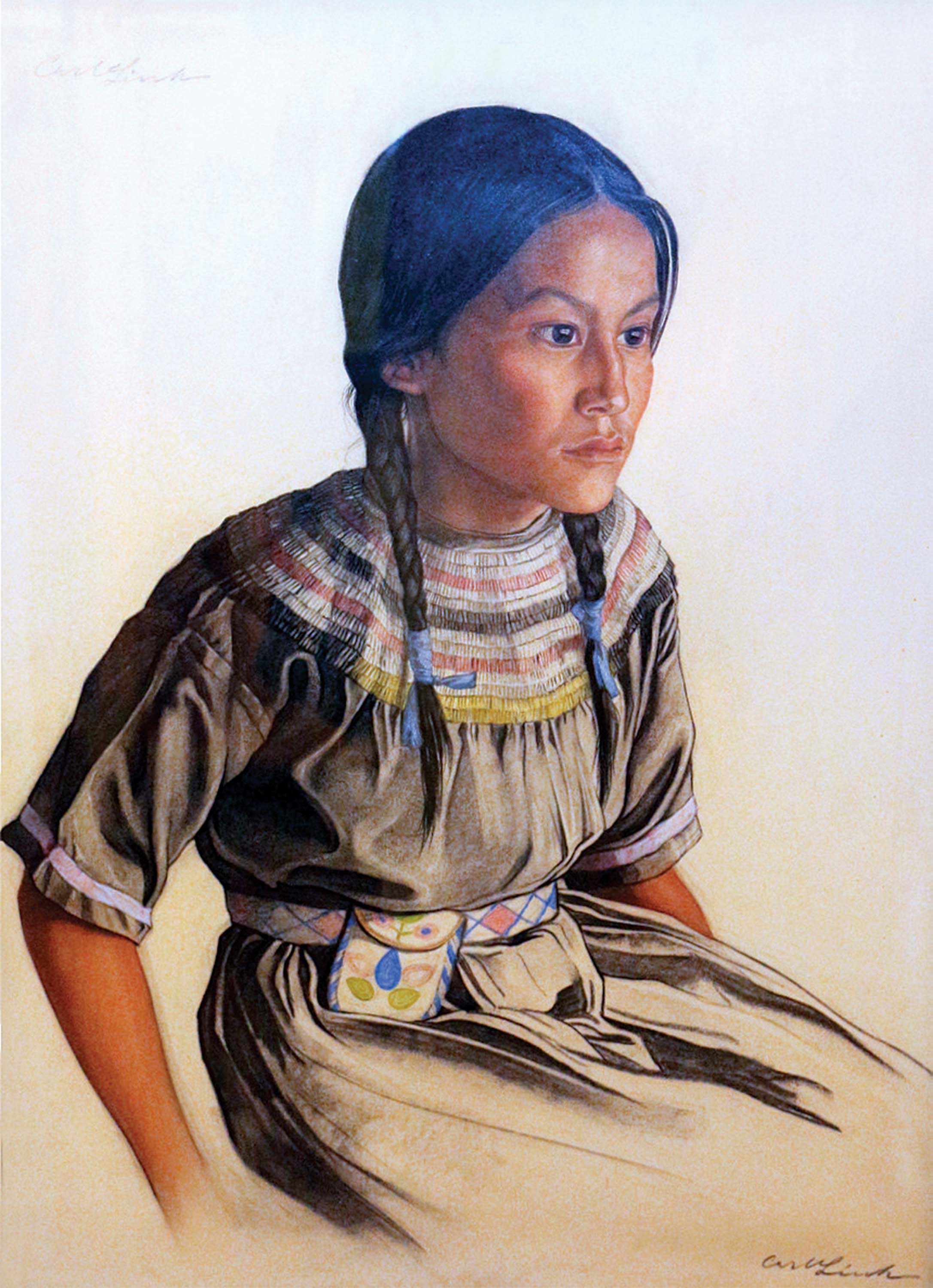

- Carl Link | “Untitled” Gouache and Watercolor | 23 x 31 inches

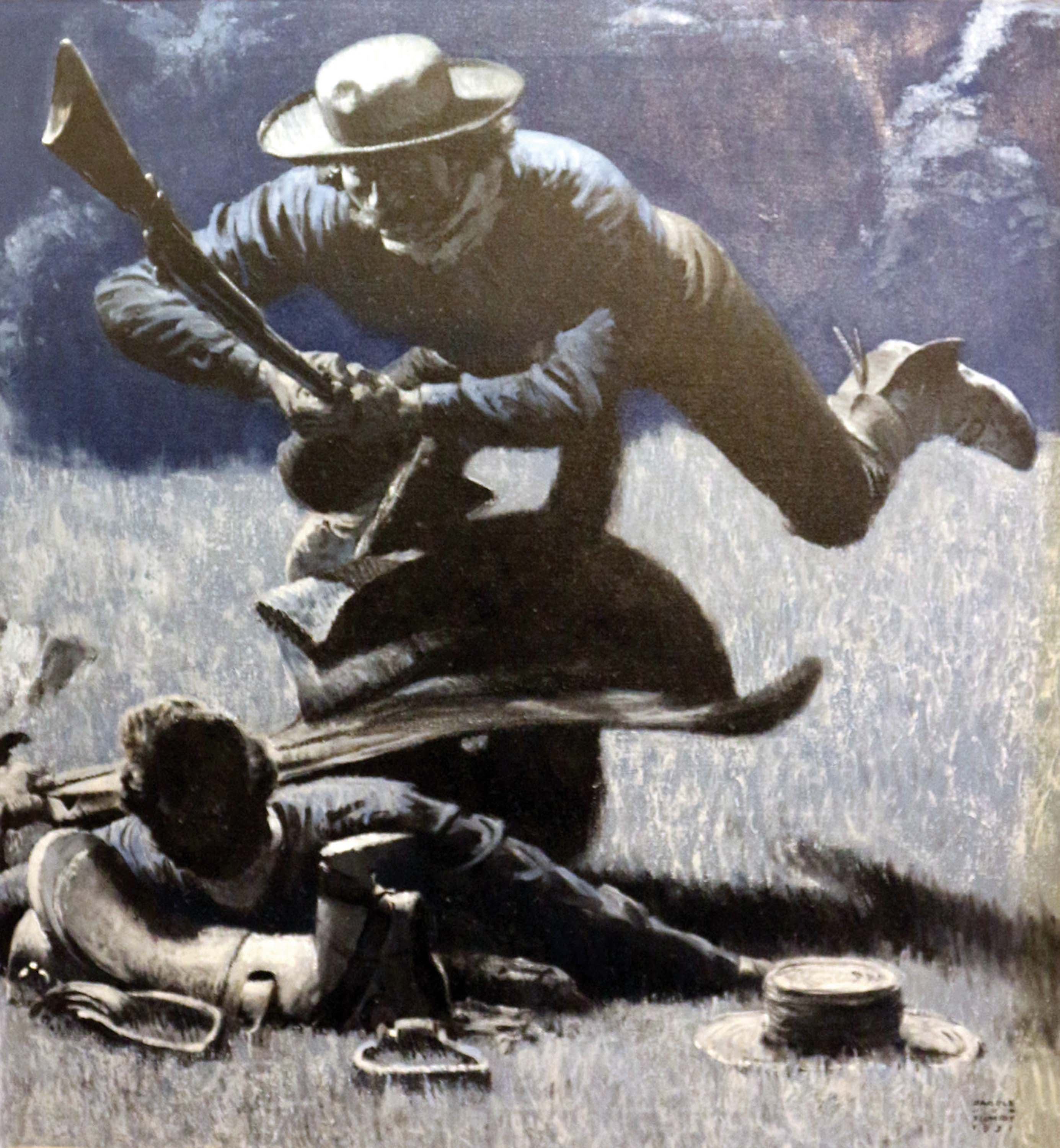

- Harold Von Schmidt | “Comanche Attack” | Oil | 30 x 31 inches | 1931

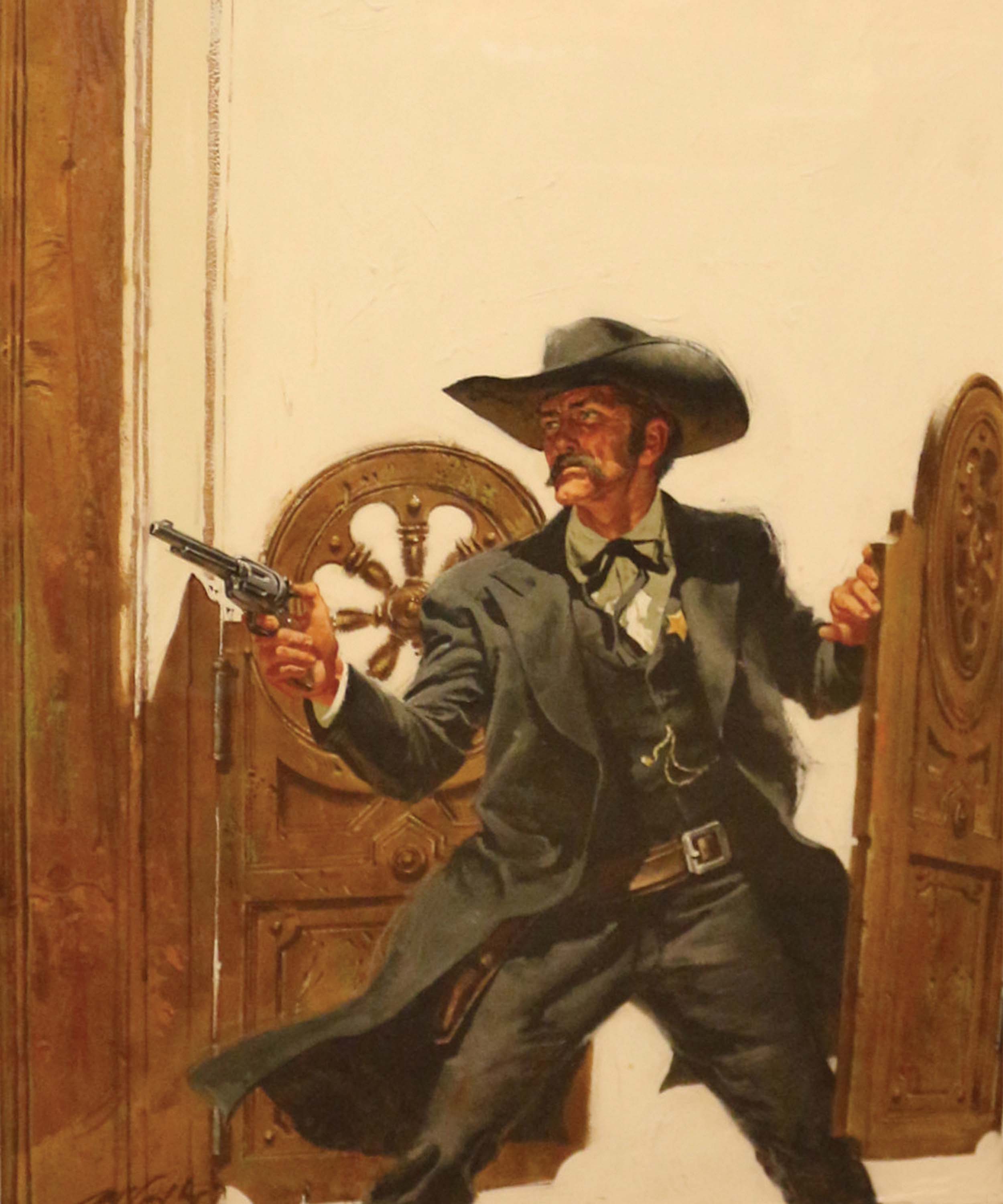

- Frank McCarthy | “Sheriff” | Oil | 15 x 17 inches

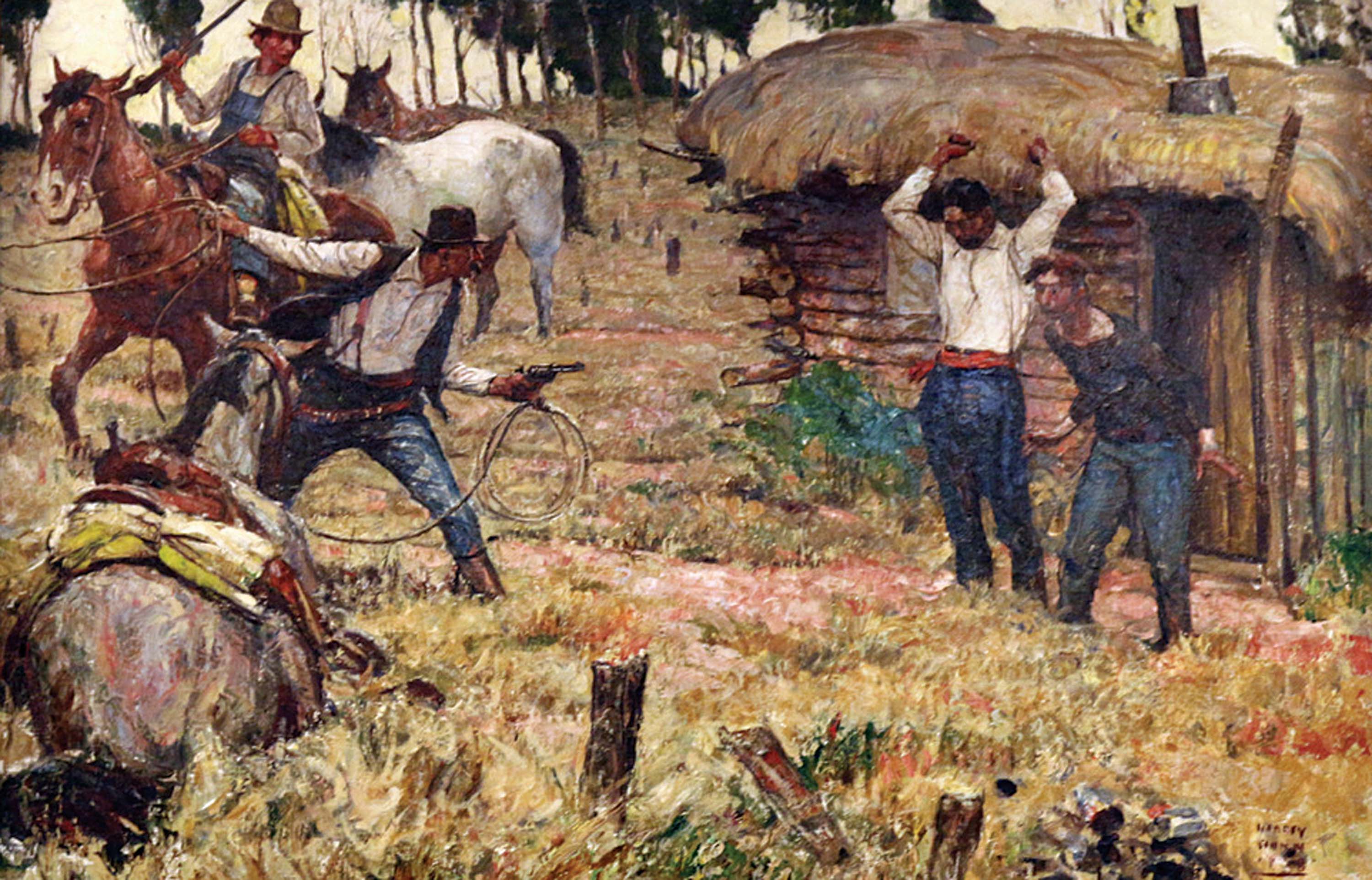

- Harvey Dunn | “Good For Me Gray Salon” | Oil | 29 x 37 inches | 1915

- Rick Hustead (left), Ted Hustead (center) and Wall Drug general manager Mike Huether (right) pose before a Harvey Dunn painting.

- Pruett Carter | “The Long Goodbye” | Oil |18 x 40 inches | 1938

- Herbert Morton Stoops | “Interrupted Supper” | Oil | 44 x 29 inches | 1940

- Harvey Dunn | “Apprehending the Horse Thieves” | Oil | 40 x 25 inches | 1938

No Comments