10 Mar Western Art Chronicles

The West has provided powerful stimuli for generations of artists. It’s a unique place, yet exists for many as an ideal, a fantasy, myth, symbol, or a time past. Artwork provides a constructive framework for us to contemplate the American West anew: its turbulent past, vibrant present, and undecided future.

To thoroughly cover the history of Western art requires a thick book indeed. The best option available today is the 2009 second edition of The West of the Imagination by William H. Goetzmann and William N. Goetzmann, which details notable artists and their contributions in about 600 pages.

For something less weighty, this WA&A Western art primer pairs artists with time periods or trends, covering nearly 200 years of history. Written by Seth Hopkins, the executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum, it provides an overview of some of the outstanding artists who have shaped this unique American art genre.

Explorer Artists: 1830s to 1850s

George Catlin and Karl Bodmer

Early Western art was largely made up of images of Native Americans, with limited landscapes. Arguably, George Catlin produced the first “Western” artwork in 1832, when he began his trip up the Missouri River determined to paint portraits and scenes of everyday life among the Native American tribes in the American West. Catlin had painted pictures of Eastern Indians, many having little of their culture still in existence. Heading West, he hoped to find tribes living much as they had for generations. He would spend the majority of his remaining years painting portraits and documenting their lives.

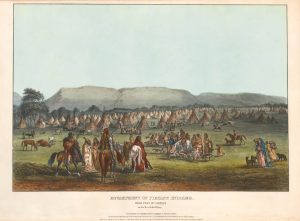

Karl Bodmer, Encampment of Piekann Indians | Hand-Colored Lithograph on Paper | 14.1875 x 20.0625 inches | 1842 | Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Betty A. and Lloyd G. Schermer

Another artist who sought to record images of the American Indian for posterity was Karl Bodmer, a Swiss painter who accompanied Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied on an exploration of the West in 1833. Bodmer was a better artist and paid more attention to detail than Catlin, though he lacked the former artist’s enthusiasm for his project. Bodmer’s work was meant to merely illustrate the prince’s journals, but his imagery quickly became famous on its own.

Catlin and Bodmer, along with John Mix Stanley, Alfred Jacob Miller, and others, set the stage for what we call Western art today.

Heavenly Landscapes: 1860s to 1900s

Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran

Thomas Cole’s 1825 painting Falls of the Kaaterskill almost single-handedly transformed American art from portraits to landscapes by the 1830s. It also etched his name in the art history books as the founder of the Hudson River School. Soon, Americans were taking pride in their country’s picturesque landscapes, particularly those captured by artists working out West.

Albert Bierstadt, Among the Sierra Nevada, California | Oil on Canvas | 72 x 120.125 inches | 1868 | Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Helen Huntington Hull, granddaughter of William Brown Dinsmore, who acquired the painting in 1873 for “The Locusts,” the family estate in Dutchess County, New York

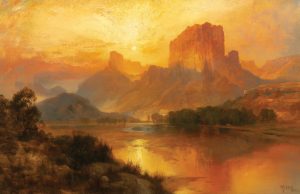

Albert Bierstadt is closely associated with the region that became known as Yosemite National Park, the first area set aside as a preserve in the 1860s. Meanwhile, Thomas Moran’s paintings of Yellowstone prompted Congress to designate the region as the first national park in 1872. The artist began signing his paintings with TYM, Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran.

Thomas Moran, Green River, Wyoming | Oil on Canvas | 13.25 x 20 inches | 1883 | Courtesy of the Coeur d’Alene Art Auction

The two rival painters would spend the rest of the century crisscrossing the West in search of iconic views. The California coast, the Grand Canyon, and the Rocky Mountains became their battleground, and we are the beneficiaries. Depictions of these spectacular Western landscapes became very popular. They were something different and unique, compared to the lands of Europe, easing whatever inferiority complex the young country felt.

The Two Big Rs: 1890s to 1920s

Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell

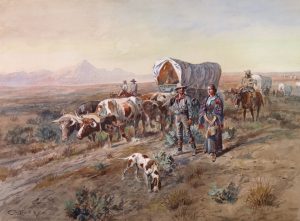

Charles M. Russell, Last Chance or Bust | Watercolor | 21 x 29 inches | 1900 | Collection of the C.M. Russell Museum; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Stephenson

Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell are the artists most readily identified with the West, and they are so intertwined it’s almost as if they are one entity. While each had his own style — with strengths and weaknesses — they both sought to achieve similar results. They believed the West of their mature years was not the same as that of their youth, and they sought to preserve the region through somewhat nostalgic images. Despite Remington’s death before the age of 50, he and Russell produced significant bodies of work in painting and sculpture.

Frederic Remington, Custer’s Last Charge (A Sabre Charge) | Oil en Grisaille on Canvas | 25 x 35 inches | ca. 1896 | Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Russell is cast as the cowboy-turned-folk-artist who lived in the wilds of Montana and produced heartfelt renderings of a fading epic. Meanwhile, Remington plays the role of a New York city slicker who had traveled West a few times. He was attempting to shake the illustrator label, and wanted to be mentioned in the same breath as the great artists of the day. And while these stereotypes contain enough truth to survive, ironically, the artists’ earliest years were almost the opposite of these depictions. Russell grew up in a fairly well-to-do family in St. Louis, Missouri, near the botanical garden. Remington’s formative years were spent in a much more wilderness-like region in Upstate New York.

Taos Titans: 1900s to 1930s

Joseph Henry Sharp and E.I. Couse

The epicenter for Western art shifted from the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains to New Mexico in the early 1900s. Among the strongest performers within the art market in recent decades have been works by the members of the Taos Society of Artists, particularly the six founding members: Joseph Henry Sharp, Eanger Irving Couse, Bert Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, Oscar Berninghaus, and Herbert Dunton. All were from or had ties with the Midwest and studied art in Europe.

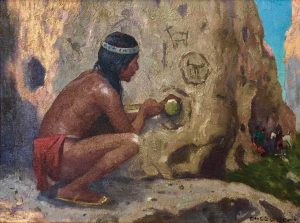

E.I. Couse, Pictographs | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 16 inches | 1911 | Courtesy of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site

These artists came to New Mexico to establish an American tradition that was separate from Europe. It would be based on uniquely American subjects — the Native Americans of Taos Pueblo — who lived much as they had for centuries, along with the organically folded landforms in the area and the quality of the light some artists compared to that of Giverny, France. Eventually, the Taos art colony would attract artists from all over the world, including influential Russians like Nicolai Fechin and Leon Gaspard.

The Taos Society would have roughly 20 members over its history. With the support of significant patrons and the Santa Fe Railroad, the group mounted exhibitions of their work at major museums on the East Coast and in Midwestern cities. Its members won numerous important national art contests. Prior to the Great Depression, the group fell apart as many had achieved significant individual success, and the ongoing workload did not seem worth the effort.

Joseph Henry Sharp, Papoose | Oil on Canvas | 19.25 x 15.5 inches | 1932 | Courtesy of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site

Couse and Sharp are arguably the best-known members of the group; both were prolific and produced a number of romantic firelit scenes of local Taos Puebloans engaged in tasks more often associated with Plains Tribes. The two titans lived and worked next door to each other, and the Couse-Sharp Historic Site is one of the best-preserved and most historically significant art sites in the country.

Just down the road in Santa Fe, artists were also flocking to town. However, no organization resembling the Taos Society of Artists was ever established. Instead, Edgar Hewett, the first director of the New Mexico Art Museum, allowed artists to use gallery space to show their work and created a strong art tradition for the community.

Hewett and the museum also supported a small group of young artists — Los Cinco Pintores — consisting of Will Shuster, Fremont Ellis, Walter Mruk, Jozef Bakos, and Willard Nash. However, this group — sometimes derisively described as the “five nuts in the five mud huts” — never attained the stature of their Taos brethren.

Even in today’s market, the works of similarly trained, competent artists who paint subjects associated with the Taos Society can bring two to four times the hammer price at auction compared to artists based in Santa Fe. Conversely, Santa Fe has become a dominant art market on the American landscape. With a total population of only about 70,000 people, the city supports nearly 250 art galleries, making it America’s third-largest art market behind New York City and Los Angeles.

Modernism Comes West: 1930s to 1960s

Maynard Dixon and Georgia O’Keeffe

The period bookended by 1930 and the early 1960s proves to be difficult to define. Despite a profusion of Western movies, the continued popularity of Western pulp magazines filled with illustrations, and later television programs, surprisingly little fine art of note depicting Western subjects was produced during these years.

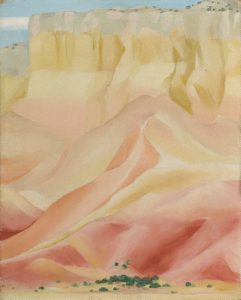

Georgia O’Keeffe, My Backyard | Oil on Canvas | 10 x 8 inches | 1945 | Courtesy of Sotheby’s

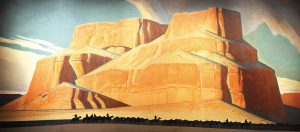

Among the “lone wolves” creating Western images during this period, Maynard Dixon and Georgia O’Keeffe are the best known. Both embraced elements of Modernism in their work, thereby broadening the size of their potential audiences and attracting Western and modern art fans.

Dixon had sent Remington some sketches asking for a review while still in high school. Remington reportedly responded that Dixon drew better at his age than he had. Living and working in San Francisco, Dixon was advised to travel east to see the West. He did so regularly and established a studio near Zion National Park, which you can still visit. Dixon’s best works show his obvious love of the region rendered in somewhat Cubist or similarly modern techniques.

Maynard Dixon, Red Butte with Mountain Men | Oil on Canvas | 96 x 214 inches | 1935 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

O’Keeffe transcends the Western genre, claiming her rightful place as an American master painter. However, the sheer number of images she created of the Western landscape, particularly around her hometown of Abiquiu, New Mexico, and nearby Ghost Ranch, make her more than worthy of inclusion in any Western art history discussion. She so loved the West that she generally abandoned her living spaces in both Upstate New York and Manhattan. Instead, she fixated on the desert, flowers, and landmarks like Pedernal, the mountain she said God had told her if she painted it often enough, he would give it to her.

The art produced by both Dixon and O’Keeffe is an often-noted influence on the work of many contemporary artists today.

Defending Realism: 1960s to 1980s

John Clymer, Robert Lougheed, and Frank McCarthy

It becomes more challenging to speak with certainty as we approach the present day, losing the time and distance required for clear hindsight. However, of note is the year 1965, when four cowboy artists met in a saloon, of all places, to found the Cowboy Artists of America (CAA). While this doesn’t seem like a bold step today, it was deemed radical and counterculture by some at the time. Art curator Jerry Smith has likened the CAA to the Pre-Raphaelites, swimming upstream against the tide of Modern and Postmodern art movements such as Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

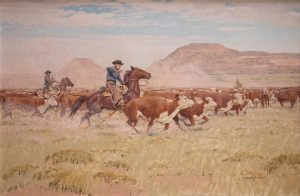

Robert Lougheed, Round-up at Seago Mesa – Bell Ranch | Oil on Canvas | 26 x 36 inches | Date Unknown | The Frank Harding Collection | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

The group was founded by artists Charlie Dye, John Hampton, Joe Beeler, and George Phippen. The founders intended to create a social club that offered mutual support for those attempting to make a living creating traditional Western art. Their stated desire was to perpetuate the memory and culture of the Old West, as typified by the late Remington, Russell, and others.

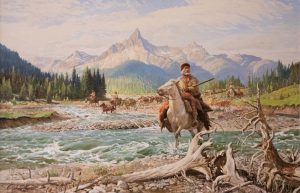

In many ways, John Clymer, Robert Lougheed, and Frank McCarthy were among the most influential artists of this period. Clymer created heavily researched and well-documented depictions of mountain men who followed in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark, establishing fur trading posts and harvesting beaver from the creeks and rivers of the Rocky Mountains. He also created a series based on Lewis and Clark’s trip to the Pacific Ocean and back.

John Clymer, Fur Brigade | Oil on Canvas | 35 x 47 inches | 1970 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Lougheed is an important Western painter, but he’s likely even more important as a teacher who significantly influenced two generations of young artists. For many summers, he co-hosted painting workshops and critiques with Clarence Tillenius on the Okanagan Game Farm in British Columbia. Artists ranging from Harley Brown and Randal Dutra to John and Terri Kelly Moyers — who met there and later married — were able to paint animals from life and get important feedback from Lougheed.

Frank C. McCarthy, The Long Trail West | Oil on Masonite | 36 x 60 inches | 1973 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Meanwhile, McCarthy brought many new collectors to the Western art fan club with his action-packed compositions that were available as limited edition prints at affordable prices. The anonymous founder of the Booth Western Art Museum, like many others, bought McCarthy prints for years, later transitioning to buying originals.

Native American Influences: 1960s to 1990s

Allan Houser and Fritz Scholder

In 1962, the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) was founded in Santa Fe under the jurisdiction of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. Initially set up as a high school, it is now a four-year college that grants degrees in arts disciplines and several other areas. The IAIA provided an opportunity for young Native Americans with artistic talent to leave their homes, often on reservations, and live on the Santa Fe campus while working to develop an art career. The school offered instruction in drawing, painting, sculpture, jewelry making, and other specialties, along with liberal studies, art history, and encouragement for students to investigate their own family and tribal history.

Allan Houser, Mescalero Drummer| Bronze | 25 x 27 x 14 inches | 1984 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Previous attempts to provide young Native American artists with training were often led by non-Natives who usually had preconceived ideas about what style and subjects were appropriate. IAIA was primarily led by Native Americans who had arts or business backgrounds. They provided ample supplies, studio time, and reassurance that experimentation is essential to moving art forward. Within a remarkably short period, a number of students and faculty were important leaders in establishing a whole new framework for American Indian art, often merging traditional motifs, symbols, or spirituality with modern sensibilities.

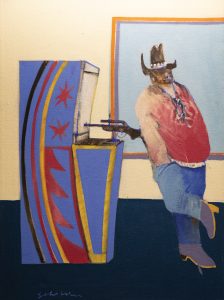

Two of the early instructors are among the most famous Native American artists. Fritz Scholder, being only 25-percent La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians, often deflected the Native label, preferring to be known just as an American artist. He also initially wanted to stay away from painting American Indian subjects, thinking they might be clichés. However, when he saw his students struggling to come to grips with ideas about identity and modern art motifs, he began a series of paintings depicting Native Americans caught in a time warp — with one foot in the white man’s world and another in the past — holding to traditions that were often hundreds of years old. An indicator of the impact the IAIA had on American art includes a Smithsonian-organized exhibition of work by Scholder and former student T.C. Cannon in 1972. The show opened in Washington, D.C., then traveled throughout Europe.

Fritz Scholder, Indian at Gallup Bus Depot | Oil on Canvas | 42 x 32 inches | 1969 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Sculptor Allan Houser, who taught at IAIA from 1962-1975, began his art career at The Studio School of instructor Dorothy Dunn in Santa Fe, where he learned to paint flat pictures with subdued color and no modeling. He later broke out of the limitations imposed by Dunn, painting works with brighter colors and more three-dimensional representations, and experimented with sculpting abstract forms. Late in his career, Houser created large-scale artworks in various materials — such as steel, bronze, and stone — influenced by Henry Moore and other Modernists.

Contemporary Champions: 1980s to Present

Howard Terpning, Martin Grelle, and John Coleman

The artistic responses to the vastness, scenic beauty, wildlife, and varied peoples of the American West created between 1830 and 1930 leave a daunting legacy for today’s Western artists. In the simplest terms, the enduring traditions established by those working in that first century leave contemporary artists two basic choices: they can generally follow the durable customs and produce art visually similar to that of preceding generations, or they may reject portions of the convention and infuse their work with aspects of modern or contemporary art. While the treatments may have changed, the landscape, cowboys, Native Americans, and wildlife are subjects that still inspire many. Some artists, going against the traditional narrative grain of Western art, have also responded with social commentary embedded in their work.

Howard Terpning, Trail Along the Backbone | Oil on Canvas | 59 x 69 inches | 2001 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

In the 1980s, some critics suggested that less traditional artists, including Donna Howell-Sickles, Ed Mell, Kim Wiggins, Tom Ross, and others, would come to dominate the field within a relatively short time. Forty years have passed since some of those articles were written, and traditional Western art is still the mainstream, with more contemporary imagery being an important but smaller tributary, at least for now.

The founding of the two different organizations — the IAIA and the CAA in the 1960s — marked the beginning of a wave of Western art popularity we are still riding today. The trails blazed by contemporary artists related to these two venerable institutions have helped create an environment in which dozens of museums have acquired works by living artists; several regular publications are dedicated to the genre; stand-alone auctions of Western art regularly include contemporary work; and numerous galleries primarily handling living artists’ work exist in Western art meccas like Scottsdale, Arizona, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Santa Fe, and beyond. Among the top-selling artists of the current period are Howard Terpning, Martin Grelle, and John Coleman.

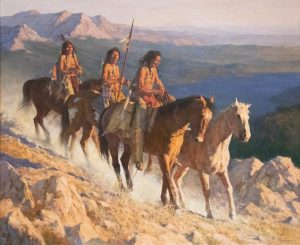

Martin Grelle, Running with the Elk Dogs | Oil on Canvas | 62 x 73 inches | 2007 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Coming off a highly successful career as a professional illustrator, Terpning moved to Tucson, Arizona, in the 1970s and began researching ideas for paintings of Native American history. He would find an enthusiastic audience, and his works were highly valued by collectors, so much so that many sold at museum shows were “flipped” by the buyer before they even left the event. Seeing this happen repeatedly, Terpning began raising his prices significantly, yet still had plenty of interested bidders. His auction prices continued to rise, ahead of his museum show or gallery prices, to the point where one sold for over $1.9 million.

Many assume Grelle to be the heir apparent to Terpning’s legacy and market, having sold a painting at auction for more than $500,000. Mentored by James Boren, but virtually self-taught, Grelle regularly takes trips to areas where he can hire models, dress them in period clothing, conceive any number of possible compositions, and take reference photographs for use in the studio. With additional historical research, it can take him well over a year to bring an idea to life on canvas.

John Coleman, Addih-Hiddisch, Hidatsa Chief | Bronze | 34 x 17 x 11 inches | 2004 | Courtesy of the Booth Museum

Coleman is one of the most popular and awarded sculptors in the West. He uses the well-known iconography of Native American traditions as a vehicle to tell universal human stories. In recent years, he has gone back to his first love, painting, and has had similar success, producing powerful portraits that convey strong emotions.

No Comments