12 Nov Where the Spirit Moves You

LET YOURSELF STAND BEFORE AN ORIGINAL PAINTING by a favorite artist and feel your spine tingle. There is no substitute for being able to see the brushstrokes, the real-life color, the subtle details up close. There’s an added magic when the work is crafted in a way that speaks to an earlier time and is imbued with an unfailing sense of place. While this experience happens most often at auctions and museums, visiting the sites that inspired the artists can bring us closer to understanding their genius.

Across the West are a few well-preserved sites where some of the most well-known works were created by some of the most well-known artists. These places — the artists’ homes and studios — allow us to step into the scenes portrayed in their art; we can imagine their daily lives and experience their surroundings firsthand. We can stand where concepts became art, where brushes whispered along canvas, where sun, sky and earth were translated through far-reaching vision. Experiencing these places can be like visiting an old friend, like coming home.

Among the historic homes and studios open to the public and set amidst the landscapes that inspired them are three that belonged to Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles M. Russell and Maynard Dixon. Each of the properties is on the National Register of Historic Places and all of them give a rare view into both the artist and the art.

Georgia O’Keeffe [1887–1986]: Abiquiu, New Mexico

Georgia O’Keeffe purchased her property in Abiquiu, New Mexico, in 1945. The 5,000-square-foot Spanish Colonial compound that comprises her home and studio was a shambles that took four years to renovate. In 1949, the artist moved from New York to make New Mexico her permanent home. She lived either in Abiquiu or nearby Ghost Ranch until she moved to Santa Fe in 1984.

“Georgia O’Keeffe’s Abiquiu home and studio opened in 1995,” says Agapita Judy Lopez, director of Abiquiu Historic Properties. The goal of the property’s opening was “to provide a better understanding of the artist’s life and artwork and allow visitors to experience her connection to the landscape and architectural spaces that served as her inspiration,” Lopez says. The artist’s home at Ghost Ranch is not open to the public.

Traveling the scenic 48-mile drive north from Santa Fe is a dreamlike journey through the scenes that inspired O’Keeffe and were often the subject of her paintings throughout her most productive years. The landscape enchanted the artist. “I’d never seen anything like it before, but it fitted me exactly. It’s something that’s in the air, it’s different. The sky is different, the wind is different,” she said about northern New Mexico in Perry Miller Adato’s 1977 film Georgia O’Keeffe. Her luscious, stylistic interpretations of rolling hills, dramatic canyons and desert artifacts come to life in this rugged environment.

The tour office is located next door to the Abiquiu Inn on US Highway 84, between mile markers 211 and 212. A variety of guided tours are offered, some including behind-the-scenes looks at O’Keeffe’s workroom and storage space as well as her fallout shelter. Advanced reservations are required. A visit to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and Research Center in Santa Fe before or after your trip to Abiquiu will enrich your experience.

Charles M. Russell [1864–1926] Great Falls, Montana

Charlie Russell longed to live a cowboy’s life and, at the age of 16, left his home state of Missouri for Montana. Working for ranchers and as an apprentice to a hunter and trader, Russell had ample opportunity to observe cowboys, wildlife and the Northern Plains Indian cultures, all of which contributed mightily to his oeuvre.

As an artist, Russell was a grand storyteller who, by the early 1900s, had become internationally known. His depictions of the Old West in paint, bronze, ink and wax drew admirers from near and far. Russell knew his subject matter by having lived it.

Now part of the C.M. Russell Museum compound in Great Falls, the Charles M. Russell home is a blue, two-story frame house built in 1900 for $800. It is furnished with period pieces and personal items from the Russell family. Russell’s studio, constructed of Western red cedar telephone poles, sits adjacent to his home and is filled with authentic cowboy gear, Indian artifacts, shelves lined with models for sculptures and other mementos the artist gathered over his lifetime. His easel stands surrounded by brushes and tubes of paint and at one end of the room is a large fireplace where the artist cooked his coffee and beans and swapped news with his many visitors. The 4,000 or so works of art that Russell produced during his lifetime — the vast majority in this very studio — shaped the way the world perceived the American West.

The C.M. Russell Museum maintains the most complete collection of Russell art and memorabilia in the world. It opened in 1953 in a small gallery. Subsequent expansions brought the museum campus to its current capacity of approximately 70,000 square feet. There are daily guided tours and reservations can be made for docent-led private tours or you can explore on your own.

Maynard Dixon [1875–1946] Mt. Carmel, Utah

In 1933, Maynard Dixon and his wife, the renowned photographer Dorothea Lange, took their two small sons to Zion National Park and then east to Mt. Carmel Junction where they camped for several weeks. It was there the artist fell in love with the high-desert landscape that would dominate his art.

A few years later, Dixon and his second wife, artist Edith Hamlin, bought 20 acres in beautiful Long Valley, Utah, and designed and built their home out of logs and local stone. From 1939 until Dixon’s death in 1946, they spent every May through November there. The billowing cloud formations looming over the nearby farmlands and the impressive, everchanging play of light on the white sandstone cliffs and in the deep canyons’ purple shadows called to Dixon. He was also fascinated by the area’s long history of human habitation. His paintings, murals, drawings and illustrations reflect the land’s bold beauty and record the lives of its settlers and the ancient ways of early Native Americans.

When Paul and Susan Bingham acquired the property, by then expanded to 49 acres, they established the Thunderbird Foundation to preserve and protect the historic site and make it available to the public. From early spring through fall, it is possible to visit the home, studio, outbuildings and grounds of the Dixon homestead. Appointments are required for docent-guided tours.

True to its heritage, the Dixon homestead hosts artist events throughout the year. American painter Charles Muench spends time working at the site. “A landscape has a unique personality and Maynard Dixon Country has aspects to its character that range from the grandiose to subtle whispers. Looking out on Sugar Knoll, I can hear elements of conversations between the rock, the piñons and Mr. Dixon. It motivates me to create a unique and personal conversation with the land. The annual artists’ gatherings here are, at their core, a celebration of the creative spirit of Maynard Dixon,” he says.

Nestled in the shade of cottonwood trees, the 1,200-square-foot log home has been carefully maintained. All floors, paneling and doors are original, as is the coral-hued sand chinking. Throughout are pieces of furniture used by Dixon, personal belongings, historic photographs and reproductions of several of his most important paintings. Views in all directions echo scenes he painted — broad, tilted terraces that step up in great vermillion, pink, white and gray cliffs exposing 200-million years of dramatic geological history, reaching into an endless sky.

- This roofless room is located in the Georgia O’Keeffe house in Abiquiu, New Mexico. Photo: Herb Lotz

- In this 1908 photo, a gift of Ralph and Fern Lindberg, Charles M. Russell poses in his studio.

- The main room of the Dixon studio includes an original portrait of Maynard Dixon by Edith Hamlin Dixon, an original rope-springs sofa from the Dixon cabin, a bronze sculpture of Maynard Dixon by Gary Ernest Smith, and an old Navajo rug purchased from a private collector.

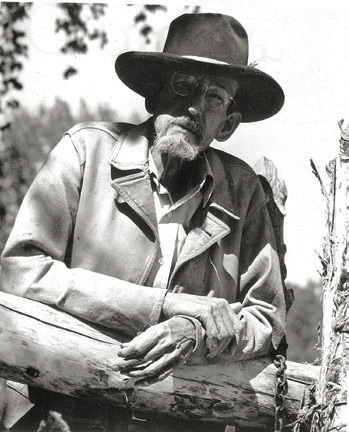

- Maynard Dixon stands at the front gate in Mount Carmel. Photo: Ansel Adams, courtesy of John Dixon and the Thunderbird Foundation

- This 1930 photograph of Russell’s studio was taken by H. C. Eklund and was a gift of Richard Flood II. Photos courtesy of C.M. Russell Museum

- Dixon’s original reading and writing desk are still in his bedroom. Other items shown include a reproduction of his painting “Cottonwood Crossing,” 1944. On the bookstand are “Rim Rock and Sage,” Dixon’s poetry, a 1977 publication of the California Historical Society, and a photo of Maynard and Edith Dixon, circa 1940. Photos: Dan Bingham

- Charles M. Russell works at his easel in his studio, 1910. Photo courtesy of C.M. Russell Museum

- The patio at the Georgia O’Keeffe house in Abiquiu, New Mexico, is stark and geometric. Photo: Herb Lotz | All images © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

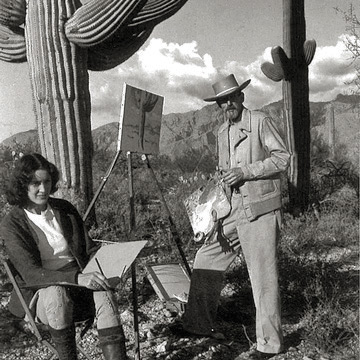

- Maynard Dixon and his second wife, artist Edith Hamlin, were photographed by Ansel Adams, circa 1942, in Tucson, Arizona. Photo: courtesy of the Dixon family and Edith Hamlin and the Thunderbird Foundation

- O’Keeffe was photographed with Pelvis Series, Red with Yellow in 1960. Photo: Tony Vaccaro | All images © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

- Georgia O’Keeffe was photographed by Alfred Stieglitz, circa 1920–1922, a gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation. Photo courtesy of Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

- The original shed where Dixon painted was also used as a dark room by Ansel Adams. The painting is a reproduction of Dixon’s Low Country Cottonwood, 1940 (the original is in a private collection).

No Comments