09 Jun William Haskell and Kim Wiggins

THEY JOKE THAT THEY FINISH EACH OTHER'S PAINTINGS. And, in truth, fine-art painters William Haskell and Kim Wiggins assist each other all the time.

You might see similarities when Manitou Galleries’ Santa Fe location debuts Western Regionalism on July 6, a show featuring new works from these two artists. Not only do the two friends show at Manitou, which has another location in Cheyenne, Wyoming, but each is drawn to the West, and in particular to Western landscapes. Both live in New Mexico — Wiggins in Roswell, Haskell in Galisteo. Both usually work from sketches before tackling full-scale paintings. Both use bold color. They’re similar in age; Haskell’s 48, Wiggins, 52. Heck, they even could pass for brothers, or, at least, cousins.

But finish each other’s works? They’re laughing when they say that, because for all their similarities, Haskell and Wiggins are as different as Charles M. Russell and Jackson Pollock.

“We like to pair artists in a joint show who have totally different styles and subjects,” Manitou owner Bob Nelson says. “Mr. Haskell and Mr. Wiggins differ from many of the other artists at the gallery because of their style of painting. Both artists are easy to recognize without trying to read a signature, and we believe that is important in the current art market.”

Wiggins paints primarily in oil. Haskell prefers using the drybrush technique on watercolor. Haskell was born in Wisconsin. Wiggins is a native New Mexican. Wiggins cites his primary influences as Hispanic folk art; his artist uncle, Bill Wiggins; and his photojournalist father, Walt Wiggins. Haskell points to Andrew Wyeth, Winslow Homer, Thomas Hart Benton and the Taos masters.

Haskell began painting full time after moving to New Mexico 10 years ago. Wiggins had his first experience in the art market when he was 12 years old. Wiggins often uses exaggerated form; Haskell is more natural.

Even their methods are different.

Haskell, for example, likes to listen to audio books while he paints.

“To me, a good painting tells a story,” he says. “I listen to literature as I paint because it kind of puts me in a place. And I try to pair a book to whatever I’m working on. It gives me the right mood, and you want it to have a mood.”

Wiggins? He’s into music.

“I listen to everything from Dvorak to the Rolling Stones to Blake Shelton. You can go down the list. It depends on the month. And a lot of times I don’t have anything on at all.”

Haskell will finish his work with a varnish, nontraditional for watercolor. “I like the way it presents the work,” he says. “People can get closer to the work. It makes the colors more vibrant. It takes that barrier away. You feel like you can step into the painting.”

Wiggins prefers a heavily loaded brush producing a thick impasto.

“This gives a wonderful three-dimensional effect to the viewer, but it would turn into a big problem if I worked the entire canvas all at once,” he says. “I would constantly be disturbing the impasto if I didn’t paint from the most distant subject forward. So I paint in layers … the sky and horizon … the middle ground … the foreground. Finally the details in the foreground and on the figures are added last, and the painting is varnished with a Damar varnish.”

Both artists, however, are admirers of the Regionalist art movement, and both are continuing that movement in America.

“I think my work has a very strong feel as American art,” Wiggins says. “I don’t think anyone would mistake my work for anything other than pure American work.”

Adds Haskell: “American art is the best there is. Studying history, which I’ve done a lot of, if it wasn’t done in France, it wasn’t worth looking at. But I think the American artists are the best, and we have so much to reflect on in this country.”

That reflection winds up in the works of both artists.

“There are so many things here [in America] that you can paint forever,” Haskell says. “We’re not even close to addressing the great images that are here in this country.”

So Haskell has painted everything from the Northeast to the Midwest. Wiggins, on the other hand, has envisioned cityscapes of New York and Philadelphia to pastoral scenes of California vineyards.

But mostly they are inspired by the West.

“We are continually delighted by the visual insights in [Haskell’s] landscapes, the play of the sky, the movement in color and shadow, and the presence of life and nature,” says Linda Off of Santa Fe. She and her husband have collected many of Haskell’s paintings. “People are not in Bill’s paintings, and yet, the hints are there. Bill’s paintings deepen your awareness of where you are, what you see, what you experience, where Bill is painting, and how everything interplays.”

That lack of human is intentional, Haskell says.

“Usually, for a human footprint, I try to put a structure in or a truck, without actually putting the person there,” he says.

Wiggins, however, will tackle historical subjects — Custer’s Last Stand, the Alamo — full of people. For this trait he has been invited to the Masters of the American West, an annual show at the Autry National Center in Los Angeles for several years.

“Kim Wiggins brings a different perspective to the Masters of the American West,” organizer John Geraghty says. “His colorful designs and compositions are original and uniquely different. It is interesting to observe the recognition and demand for his work increase each year.”

As close as these two are, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Wiggins has persuaded Haskell, an admitted history buff, to tackle some historic subjects.

“That’s something I plan on exploring,” Haskell says. “I think you have to do that or you’re going to find that your work is going to get stale.”

Stale definitely doesn’t describe either of these artists’ works.

“The art of Kim Wiggins is very unique both in style and color,” Nelson says. “His compositions are all his own, and the varied subject matters that he paints show that he is truly a master of his craft.

“The art of Bill Haskell has a wonderful serenity about it, and his palette is very soothing. Customers are drawn to the subject matter he paints as being indicative of a ‘time past.’”

You’ll even find Haskell’s paintings hanging in Wiggins’ home, and vice versa. Because one thing each artist has in common is a tremendous respect for the other’s work.

“He’s been able to tame watercolor,” Wiggins says of Haskell. “Watercolor has its own mind. Bill handles it in drybrush and does things with it that I certainly admire.”

“What I admire the most about Kim’s work is the fact that he has created his own completely recognizable style of painting with a richness and subject matter that will endure the test of time,” Haskell says. “He is a great storyteller. His paintings draw you in from a distance and up close. His work is very energetic and layered with meaning.”

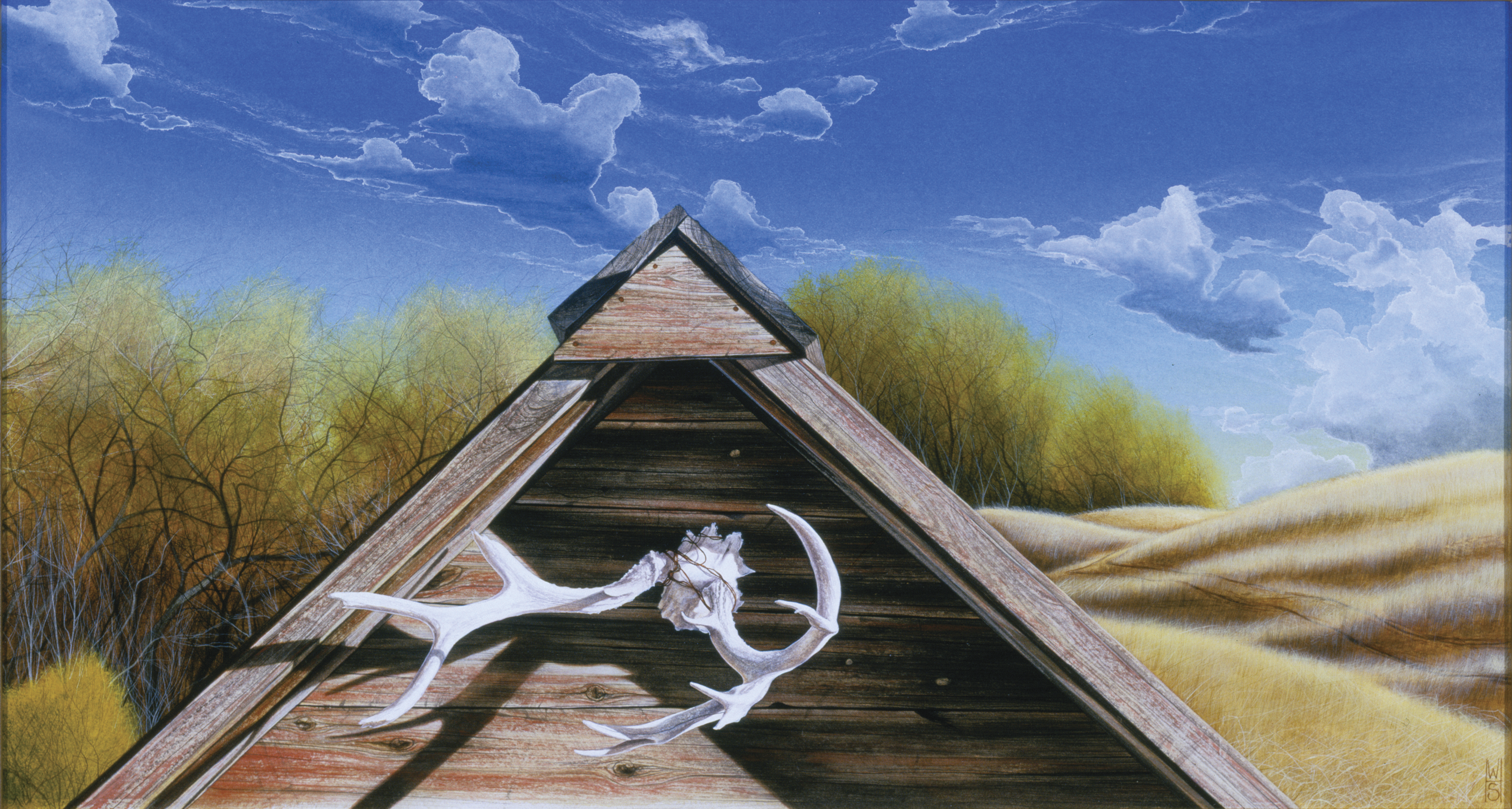

- Wiggins layers colors on his canvas. Photo: Zach Wolfson/Beyond the Gallery/ZWFILM

- Haskell applies fine detail to a painting. Photo: Zach Wolfson/Beyond the Gallery/ZWFILM

- Kim Wiggins, “Custer’s Last Stand” | Oil | 48 x 60 inches

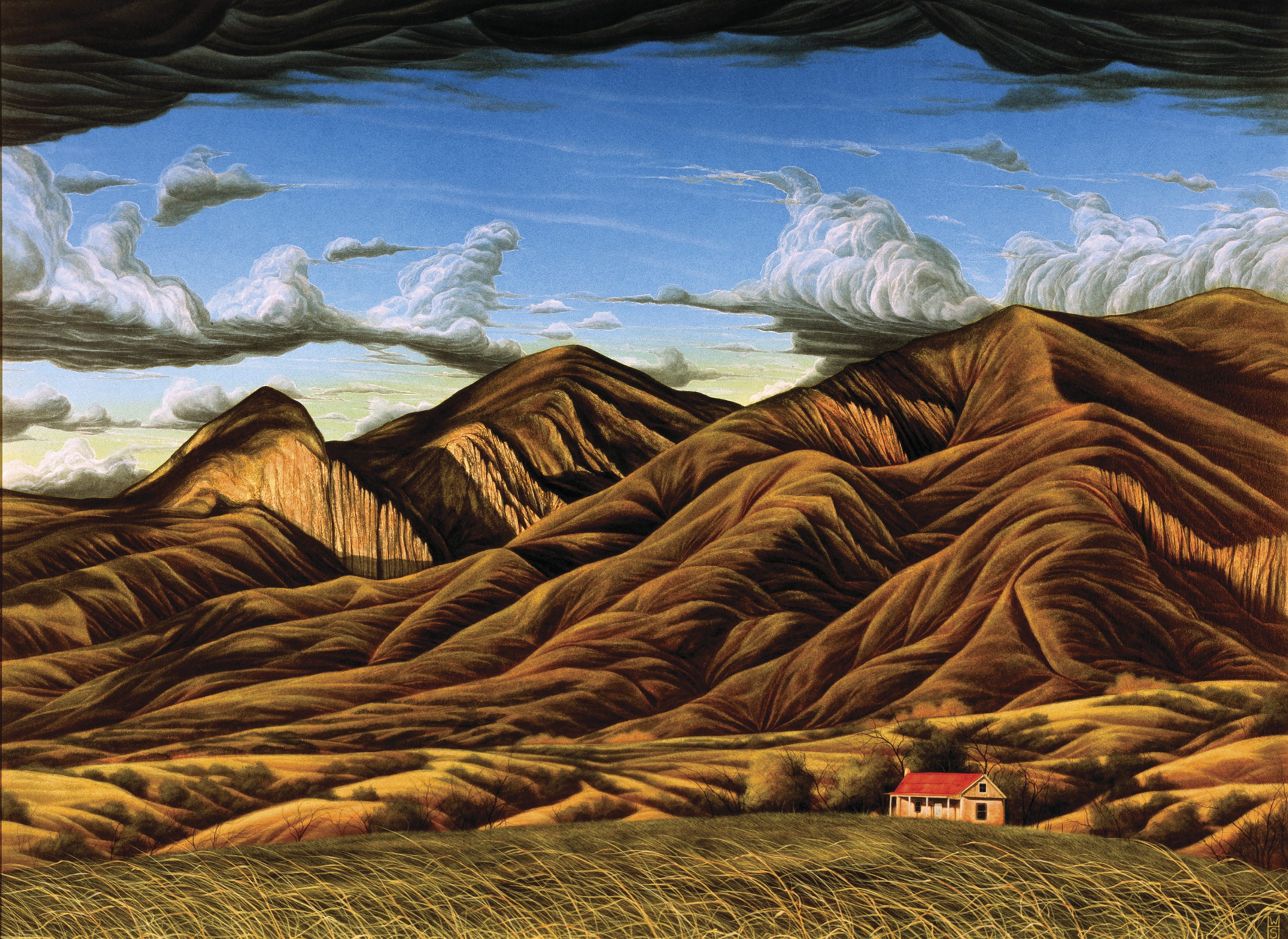

- William Haskell, “Northern Homestead” | Drybrush | 22 x 30 inches | 2010

- William Haskell, “Back Country” | Drybrush | 10 x 19 inches

- Kim Wiggins, “Prairie Fire” | Oil | 48 x 60 inches

No Comments