15 Jan In the Studio: A Ring of Truth

What makes Charlie Ringer a contemporary Western artist isn’t subject matter — or geography — although the Montana metal artist has cut, ground, and welded into being any number of bison and swirling trout. Instead, Ringer embodies the ethos of the West populated by cowboys, farmers-turned-pioneers, and those bucking tradition to carve out a life based on equal parts physical labor and ingenuity.

Ringer’s “scraptures” utilize the remnants of shapes cut from plate steel. Artie greets guests and reflects Ringer’s humorous side. | Wheels of all shapes and sizes function as both decoration and potential material for indoor and outdoor sculptures, many of which are on display throughout the Ringers’ 6-acre Montana property.

Although he neither rides nor keeps horses on the Joliet property where he has lived with his wife, Emily, for nearly 50 years (unless you’re counting iron horses, in which case he’s partial to BMW motorcycles), Ringer has been as effective a steel-whisperer as any bronco buster, learning its secrets, bending it to his will through forge and force.

In his studio, the artist prepares a metal component which will become part of a larger work.

“I mostly use metal with my sculptures because of the strength, durability, and, with persuasion, flexibility,” says Ringer, whose permanent installations are included at the Yellowstone Art Museum and Billings’ Logan International Airport.

In some of his sculptures, he’s lassoed the wind, curving surfaces to enhance movement. In his kinetic pairings, he attaches metal shapes to two offset pendulums; a gentle nudge makes horseback figures appear to gallop and birds fly for up to five hours. “I mostly focus on kinetic work because it has its integrity in its design when it’s still, and then it comes alive when activated,” says Ringer.

Ringer welds parts of a kinetic sculpture.

Leaving Minnesota activated Ringer, who ended up in Colorado, where he met Emily and briefly attended college, which he found as ill-fitting as his prior experiences with formal education.

One exception was the welding class he took as a teenager with his mother, Mary Ringer, who, at age 93, now lives in a cabin west of Red Lodge, Montana, where she paints en plein air during the summer. A short time later, his parents introduced him to Lyndon Fayne Pomeroy, a Montana sculptor known for such abstract, welded works as the angular Buffalo in Buffalo, Wyoming, and the two, 10-foot-tall figures holding car parts in Billings, Montana. Combined, the experiences sparked what would become a lifelong pursuit of knowledge and a framework for living.

Ringer’s gallery includes small- and large-scale works, like the brightly-colored Overhand Knot.

Ringer credits his parents for giving him the confidence to try things and Emily for being a willing partner in an adventure, which, during the early years of their marriage, meant traveling in a nearly new 1969 Ford Econoline van, towing the trailer he built to serve as his mobile art studio. It doubled as their residence as they moved seasonally in pursuit of places where Ringer could sell the 8- to 10-inch metal figures he’d been making, all the while teaching himself more about metalworking.

Ringer welds parts of a kinetic sculpture.

Intrigued with an auto junkyard on rural route 212, a conduit for Yellowstone-seekers and winter sports enthusiasts alike, the couple purchased it for a measly $6,700 (equal to $41,000 today). Over the years, the Ringers added and revised the land and buildings alike, resulting in a modest homestead that reflects a life lived frugally and with clear intentions.

Ringer walks past SW Shape on his short commute from home to shop.

“I’m after a lifestyle that is attainable by anybody,” says Ringer, who doesn’t distinguish between welding in his shop and running apples in a 100-year-old press to make that year’s batch of cider.

Indeed, although he was struck by Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs — a man employed by his father familiarized Ringer with the famous architect — he was more impressed with the lifestyle of the man who eschewed tradition to create such masterworks as Chicago’s Robie House and Wisconsin’s Taliesin.

Stacks of shapes cut from .25-inch steel await assembly.

The iconoclastic architect inspired Ringer’s series of kinetic works employing Native American geometric designs. One piece, Indian Paintbrush, was featured at the 2013 Buffalo Bill Art Show in Cody, Wyoming, where Ringer’s Prickly Pear is installed in the outdoor sculpture garden.

The artist works on a few unfinished sculptures in his forging area.

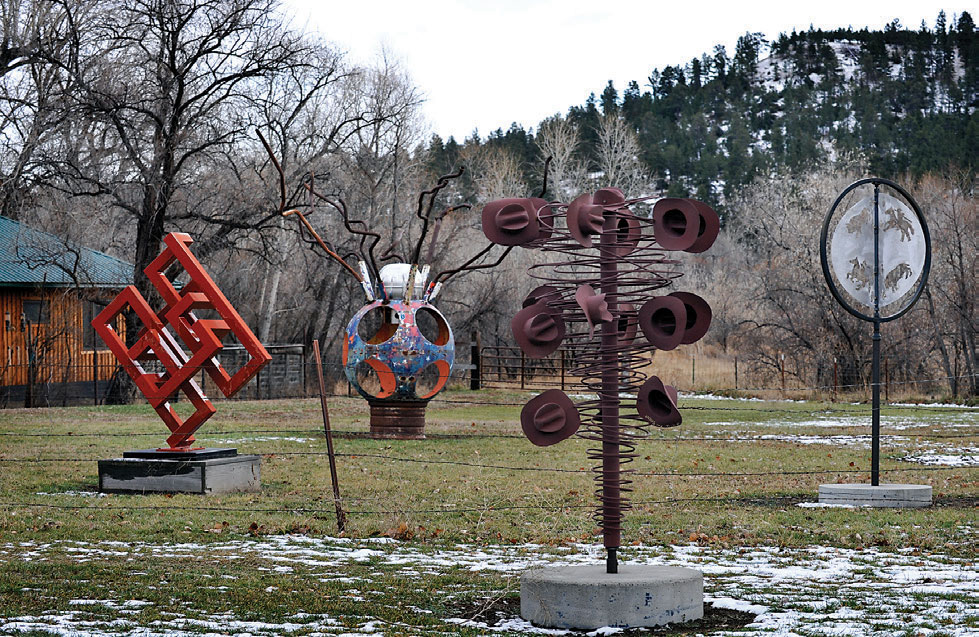

Although his work has been collected throughout the West, the best gallery viewing is on his own property. Outdoor pieces, ranging from abstract to whimsical, stand amidst manicured lawns and gravel walkways, scattered outbuildings, a few campers, and other ephemera.

Fashioned after the comic character of Mater from the movie “Cars,” this formerly operational tow truck has personality.

Facing the roadway, for example, is the 18-foot-tall Creature and a 1946 wrecker he turned into the character Mater from the movie “Cars.” Ringer converted another building into an art gallery, open regularly in the summer, and less-so in the winter. It contains some of Emily’s beadwork and other creations, a few paintings by their son, Zeb, and the work of assorted other artists, such as Linda Lucy Lunde.

Creature greet visitors to Ringer’s Joliet, Montana, property.

Most of the space is occupied by Ringer’s kinetic sculptures, which he fabricates in his nearby shop. Although many of Ringer’s more than 200 catalogued designs are repeats — coyotes, butterflies, sailboats, guitars — he prefers to draw each one individually. “I then hand-cut the images out with a hand-held plasma cutter,” he explains. After he grinds them, he makes the base, the hardest part because “it has to be accurate within a couple-thousandths of an inch.” He paints the construction with acrylic enamel, and begins assembly, including balancing the pieces, welding on the axles, and finishing with paint.

“They take 70 years to build,” he says, “or maybe it’s one day.” And that’s no tall tale; for Ringer, the work continues as long as he does.

No Comments