08 Jan Transcending the West: Teresa Elliott

STRIDING PURPOSEFULLY THROUGH SIX FLAGS OVER MID-AMERICA (now Six Flags St. Louis) on a warm June day, Teresa Elliott suddenly stopped in her tracks. In front of her was an attraction where artists sat with paper and pastels, rapidly sketching the likeness of each person who handed over a ticket. Elliott had just graduated from high school and was looking for a summer job, hoping to earn tuition money to study art. She was determined to become the first in her family to earn a college degree. What she could not have expected was that a summer of working at the theme park’s quick-draw attraction would provide the best imaginable training in drawing faces from life. It also fulfilled her original goal: She was able to enroll in the University of Kansas that fall and earned a bachelor’s degree in design and fine art.

“Sun Silenced” | Oil on Panel | 14 x 11 inches | 2017

Years later, while living in Dallas, Texas, and working as a freelance fashion illustrator, Elliott had another pivotal chance encounter. As she drove past a small pasture in suburban Fort Worth, she was struck by the beauty of a small group of longhorn cattle grazing there — the graceful curves of their horns, their gentle faces, the rich colors of their coats. She returned with her sketchpad and camera in the sunset’s warm glow, and later, she painted her first longhorn. Considering it simply for her own pleasure, Elliott never intended to sell it.

Fortunately, life had other plans. Within a few years, she received the first of many awards for her longhorn

paintings, and her work began to gain recognition in and beyond the world of traditional Western art. Among her honors over the years: Grand Prize from the America China Oil Painting Artists League, People’s Choice at the Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale, and, most recently, the Chairman’s Choice Award (for the third time) at the 2018 Art Renewal Center’s International Salon.

“The Arrival” | Oil on Aluminum | 47 x 33 inches | 2018

“Teresa is a fabulously skilled realist painter and an unmistakably Texas artist,” says Joseph M. Bravo, a Texas-based art critic, curator, and former museum director. “Yet, she’s clearly contemporary in her optic. There’s something transcendent about her work that exceeds the Southwest.”

Indeed, Elliott’s art has garnered national and international acclaim and a rapidly growing collector base. In March, she takes part in the annual Night of Artists show at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, where her work has always sold out. And then in October, Elliott and painter Jill Soukup will share a two-artist show at Gallery 1261 in Denver, Colorado.

“Beached” | Oil on Canvas | 24 x 18 inches | 2015

The world of galleries and art museums was not even on Elliott’s radar when she was growing up. As the daughter of a salesman whose work took the family to St. Louis, Kansas City, and Oklahoma City, she loved to draw but had little exposure to original art. Then, in elementary school, her parents bought a children’s encyclopedia set with a special volume on art. Sitting for hours with the big book open on her lap, she soaked up the pictures to the point that many remain imprinted in her mind today.

“Brink” | Oil on Linen | 20 x 16 inches | 2018

After her summer of intensive informal training as part of the amusement park’s quick-draw team, Elliott focused primarily on figurative art. Her skills were so remarkable that her college art professors recommended her when detectives came seeking an artist to create a police sketch of a serial rapist. Elliott met with two of the victims and asked the women detailed questions about their attacker’s appearance, sketching their responses: How far apart were his eyes, how high was his hairline, what was his mouth like? “It’s what I do while I’m working on a painting, but I just verbalized it,” she says. Her sketch turned out to be a good likeness. The rapist was caught.

When she began painting longhorns, Elliott’s talent and instincts for portraiture found a fresh focus. She saw them as individuals, with interesting bovine eyes and distinctive demeanors, worthy of the often large-scale paintings in which they appear against backdrops of gorgeous Texas skies. Her placid longhorns reflect the relative simplicity of the bovine world. “I always like the sense of community with livestock animals. To be in a pasture with that is really comforting,” Elliott says.

As curator of the Coors Western art show, publisher, and writer Rose Fredrick puts it: “She gives her subjects a sense of royalty, grace, and power, and yet there’s also something wry about her paintings, as if she’s looking back and giving a wink to old Leonardo da Vinci.”

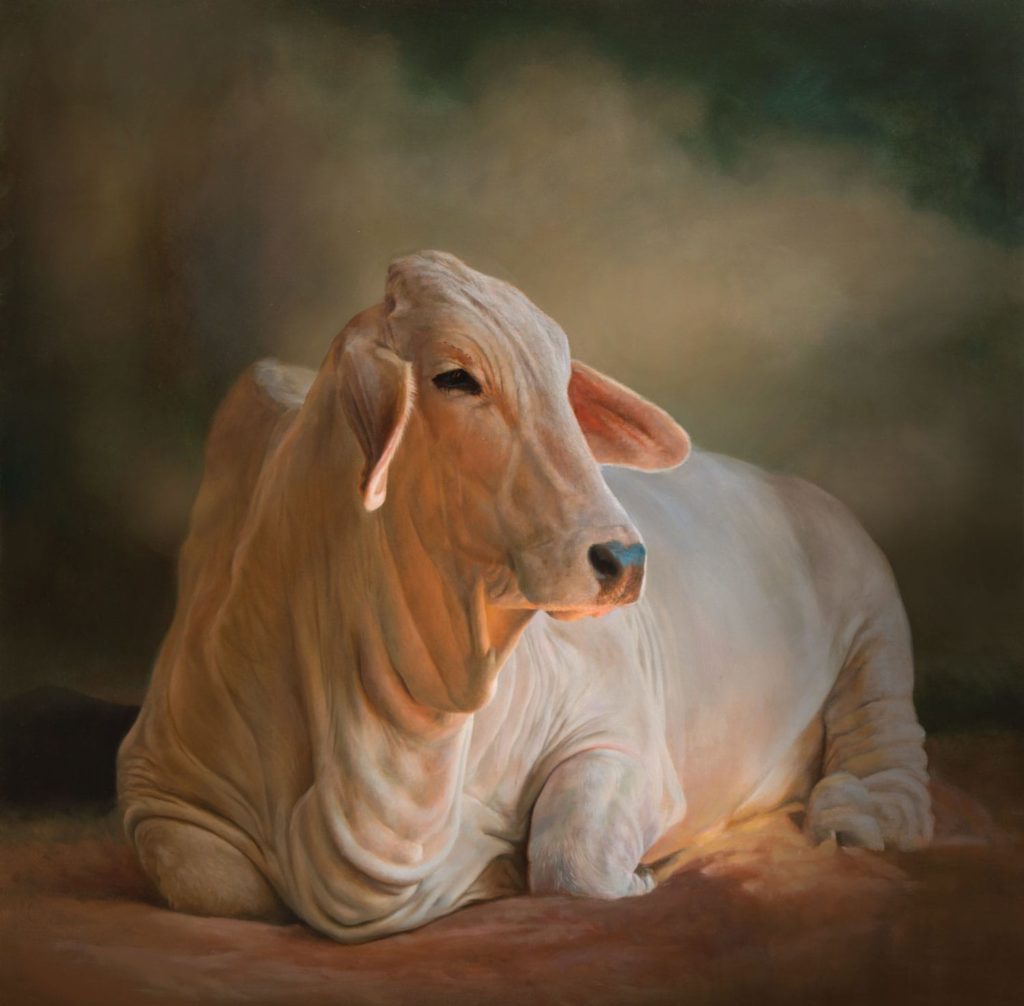

“Young Brahma” | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches | 2016

This reference to a Mona Lisa-like sense of intrigue also applies to Elliott’s figurative work. Her first large figurative painting, Deliverance, was inspired by a photo the artist had taken years earlier of her young daughter and nephews enjoying the luxurious pleasure of a pool of slick, wet clay under the Texas sun. The painting earned top awards at the 2012 Art Renewal Center’s International Salon and elsewhere, and was exhibited that year at the World Art Museum in Beijing, China. Other wet-clay paintings followed, along with striking portraits that often include subtle suggestions of narrative.

“Badlands To Cross” | Oil on Linen | 36 x 24 inches | 2018

In two works based on photos Elliott took of her grown daughter on a Gulf Coast beach, the paintings’ disconcerting feeling turned out to presage devastating events. The photos for Beached and The Arrival — both featuring a young woman in a partial gas mask — were taken close to where Hurricane Harvey made landfall in 2017. For Elliott, the paintings also touch on the complex topics of responsibility and power. In The Arrival, a fleet of military helicopters approaches behind the woman. “Women want power, and the time is coming. But with that, there is responsibility,” the 65-year-old artist says. “It’s not going to be all sweet and tiptoeing through tulips. We will have to deal with world issues.”

These days, Elliot divides her time between a lake community near Austin and the West Texas town of Alpine, finding inspiration in both places. While longhorns continue to offer themselves as subjects of surprising beauty, she finds herself on the lookout for other types of livestock, especially goats and sheep. For years, she has kept her animal and figurative imagery separate, though she envisions them converging some day. That day appears to be getting closer, she says, adding that at least one example will be in the Gallery 1261 show this fall.

“Deliverance” | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 36 inches | 2011

Elliott has discovered another surprising source of artistic delight. Her daughter is a stand-up comedian and improvisational actor, and the painter has become fascinated with the diversity and intensity of the actors’ facial expressions under theatrical lighting. Brink is one such piece. When she came across her photo of a young female actor with flaming red hair and an expression of confusion or horror, Elliott happened to be reading a biography of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of the 1818 novel Frankenstein. It’s another example of how serendipity and being open to new artistic challenges has been a major source of propulsion in the trajectory of her career. “I still enjoy painting cows,” she says, “but it’s exciting to get out of my comfort zone.”

No Comments