07 Jan In the Studio: A Sculptor’s Refuge

Steve Kestrel’s minute-long stroll from his house to the studio on 63 acres in Colorado’s Redstone Canyon, about 15 miles west of Fort Collins, often resembles more of a nature trek than a commute. “I almost always take my field glasses,” he says, the better to view the wealth of wildlife around the property where he and his wife Cindi have lived for more than 26 years. During that time, depending on the season, he’s spotted elk, bobcats, coyotes, cougars, black bears, herons, kingfishers, ravens, red tail hawks, northern harriers, “and, every now and then, a golden eagle and a bald eagle.” That’s not to mention the ubiquitous deer. “I never get tired of seeing them, even though we see them almost all the time.”

Between Kestrel’s home and studio, cottonwoods and willows follow a riparian corridor that provides refuge for wildlife. “In late summer,” says Kestrel, “we can hear the bears eating the chokecherries in there.”

It’s an ideal setting for a man who, over the past 40 years, has earned an exalted reputation as a wildlife sculptor. His works in stone and bronze are characterized by precise carving, anatomical accuracy, a keen sensitivity to materials, and exquisitely styled designs embodying a thoughtful awareness of their sometimes-imperiled subjects’ fleeting beauty. His art has been recognized with top awards at such prestigious events as Masters of the American West at the Autry Museum in Los Angeles, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Prix de West in Oklahoma City, and the Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale in Denver.

Spectre of Ancient Pathways, a 36-by-36-inch bronze buffalo, initially cast in four pieces, awaits its patina and base in the studio’s welding room.

Most mornings find him having breakfast with Cindi before he heads out the door by 10 a.m., following the 600-foot curving pathway past cottonwood trees and over a seasonal creek and pond to the 3,400-square-foot studio. The structure began as a post-frame “pole barn” built in 1952 by the property’s former owner-rancher. But what might have worked fine for ranching wasn’t going to do for a sculptor who uses heavy machinery to cut, chisel, sand, and polish giant blocks of stone. “In one corner of the big room,” Kestrel recalls of the greatest challenge he faced, “the poured concrete floor sloped 28 inches from the northwest down to the southeast corner.” Still, he adds, at the time “I couldn’t afford to tear the barn down, and I needed a dry space to work.”

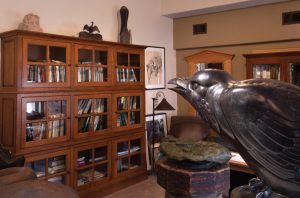

Kestrel’s Trickster Transformation, a bronze of a raven, watches over his collections of books, natural history artifacts, and works by other artists.

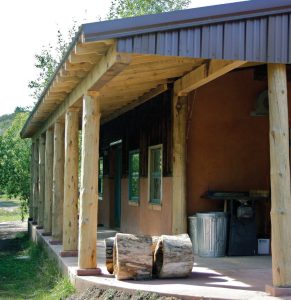

So, using a skid-steer loader, he lifted a thousand-pound granite boulder — just what a monumental stone carver has around — and moved it to the high corner of the floor. “I raised up the boulder about 10 or 11 feet and dropped it a number of times, punching holes in the concrete. Then I used the fork on the skid-steer to pop up at least half” of the old concrete before a contractor came in to pour a new, level floor. Over the years, Kestrel has continually improved the studio, adding a reinforced rafter system; new sheetrock interior walls and insulation; exterior stucco; and, in 2013, a Southwestern-style porch with exposed, carved rafter ends, harking back to his boyhood in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and on his family’s small ranch in Mancos, Colorado, within sight of the Puebloan cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde.

The eaves of the porch along the studio’s east side bring welcome afternoon shade.

Today, Kestrel’s workspace brings to mind a dazzling amalgam of an old-fashioned factory, high-tech laboratory, art and natural history museums, reference library, and magician’s workshop. All the seemingly disparate facets join forces to support the sculptor in his daily efforts to create work with a rare combination of soaring beauty and deep meaning.

Using a right-angle pneumatic grinder with a diamond head, Kestrel carves a ram’s head destined for the Prix de West show this June. “I go through leather gloves like you wouldn’t believe,” he says. The red stone, he adds, is “probably jasper, but I need to have my geologist friends look at it.”

He typically enters the building through a door on the south-facing side, next to a pair of tall barn doors. This takes him directly into the main workshop. The 40-by-28-foot space where he originally leveled the floor is now filled with a variety of rocks and boulders awaiting their aesthetic destinies, plus everything he needs to carve them: blocks and tackles for lifting, drills, saws, grinders, and chisels in a range of sizes, and a sandblasting cabinet. All the tables are on wheels, so “almost everything can be moved around,” to better tailor the space for any specific project or make room for more equipment.

On the carving room wall, a variety of diamond-grit grinding and polishing pads hang in easy reach.

At the far end, doors lead to a storeroom for his bronze molds and another contains welding and chasing equipment for joining together the pieces of cast bronze sculptures and refining seams. Most sculptors leave those tasks to the foundry, but Kestrel prefers that they be done under his own roof by Eric Johnson, “the best welder and metal chaser I’ve ever used, and just a great human being.”

For his ram’s head, Kestrel uses an array of electric grinders as well as a small hammer and chisels to knock out excess stone.

Regardless of what creative stage he may be in at any given moment, however, Kestrel’s first task is always feeding Zoey, the gray tabby studio cat. “She was a rescue from Denver,” he says. “We tried introducing her into the house, but she was a loner, and the other cats picked on her too much. So after a year, we moved her over here. She loves it.”

Sole of the Rock, made of California riverstone, won the top award for sculpture at the Autry Museum’s 2021 Masters of the American West.

On the workshop’s east wall, another pair of doors open to a room that feels more like a gallery, museum, or library, including shelves for Kestrel’s books on natural history, animal anatomy, primitive cave art, and contemporary glass artworks; and an extensive assortment of animal skulls, fossils, bird’s nests, and other natural artifacts. His own sculptures are on display everywhere — though most “are waiting either to be sold or to go to a show.”

A banner on the workshop wall features Kestrel among the eight prominent artists in the 2017 Best of the Best retrospective at the Woolaroc Museum in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

The same can’t be said for a wealth of artworks by others; many of them were traded for his own creations or gifted by other artists, Cindi, or friends. These include a signed 1937 Ansel Adams photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe with Orville Cox, head wrangler at her Ghost Ranch; prints by famed 20th-century sculptor and graphic artist Leonard Baskin; a drawing of doves and their egg-filled nest by Colorado contemporary realist Scott Fraser; and a painting by widely respected artist and anatomy teacher Jon Zahourek.

In the main workshop, boxes contain assorted rocks, slices of stone, and even a petrified dinosaur bone from which Kestrel carved playfully concealed toad eggs in his sculpture Ripple Effect. “Sometimes, when friends’ children come to the studio,” says Kestrel, “I let them pick something out of the box as a souvenir.”

Some elements in this space speak of even more personal artistic connections. A 12-foot-long antique display cabinet from a mercantile store in Elizabeth, Colorado, for example, was originally in the studio of his friend George Carlson, the longtime-respected Western sculptor and painter, whose Idaho home and studio Kestrel helped build.

His Rockfish, sculpted from Colorado schist riverstone, appeared in the 2020 Prix de West.

Beneath a shelving unit, transformed by Kestrel from a pine foundry pattern used for casting irrigation headgates, sits a 4-foot-wide flat-file cabinet from the Santa Fe studio of famed sculptor Boris Gilbertson, who mentored Kestrel starting in 1980 in the time-honored process of carving stone. After Gilbertson’s death in 1982, Kestrel worked in his mentor’s Santa Fe studio, using his tools, for two years. Kestrel, and later Cindi as well, remained close to Gilbertson’s partner Charlotte White until she passed away two decades later. Long before then, White prevailed on the couple to take the cabinet. Inside were “hundreds and hundreds of ink drawings Boris had done over decades,” says Kestrel, his voice emotional. “And we’ve still got to figure out what to do with them all.”

On the patio of their nearby home, Cindi and Steve Kestrel enjoy the company of Jake, their new Bernese Mountain Dog pup.

That trove is yet one more aspect of the nurturing artistic refuge Kestrel has built, assembled, and preserved in Redstone Canyon. “I had three different studios before we bought this place: Boris’ in Santa Fe, and then two in Fort Collins,” he says. “Now, this is by far the best and largest. There are just a lot of things I never would have been able to do if I hadn’t had this space.”

A glass case displays “curiosities,” including a fossilized trilobite and a rhinoceros jawbone.

No Comments