09 Jan Painting to Preserve Tradition

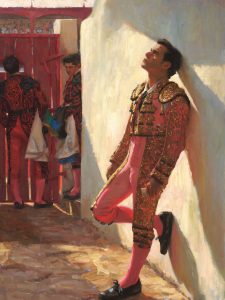

When Gladys Roldán-de-Moras tells her story of becoming a painter, it’s hard to believe fate was not involved. The San Antonio, Texas-based artist has made a name for herself in the Western art world, capturing her Hispanic heritage with a striking color palette and deft control of light. She paints various subjects — bullfighters and flamenco dancers, pastoral landscapes and still lifes — but her focus on charrería, Mexico’s national equestrian sport, has made her a kind of documentarian of the long-held tradition.

Devotion | Oil on Linen | 48 x 48 inches

“I try to portray in my paintings the beauty of my heritage as I see it — as an expat from Mexico living in the United States, as someone very lucky and blessed to be here, but trying to preserve my culture,” she says. “And, being in San Antonio, I couldn’t do it in a better setting.”

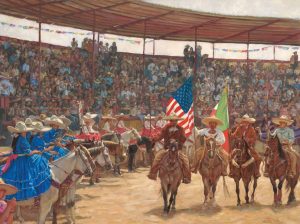

Charrería was born out of everyday ranch activities: rounding up cattle, branding, roping, and riding. Its trappings are traced back to Salamanca, Spain, but it evolved in Mexico through competitions held between haciendas. In the years following the 1917 end of the Mexican Revolution, its popularity increased as part of a movement to preserve the beloved lifestyle. The charrería competitions Roldán-de-Moras paints are held in the U.S., some in San Antonio, by expats like herself. In that way, she’s not only capturing the sport but also preserving its tradition in this country.

Fiesta Charra in Texas | Oil on Linen | 30 x 40 inches

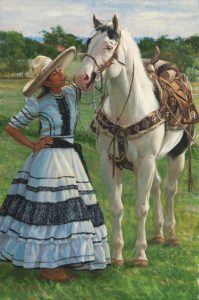

Roldán-de-Moras is best known for painting escaramuzas charras, the women’s event of charrería, which sprung up in the 1950s. These female athletes must ride side-saddle, performing synchronized equestrian feats in incredible dresses made of intricate fabrics. “I once heard it described like aquatic dancing — synchronized swimming — but on horses,” Roldán-de-Moras says. “And these girls are on horses at high velocity.”

For years, Roldán-de-Moras has deepened her knowledge of the sport, learning to paint its unique rodeo-style feats and colorful outfits with such elegance and confidence it’s as if she always did this work. But, in fact, she almost did not become a painter at all.

Roldán-de-Moras grew up in San Pedro Garza García in Monterrey, Mexico, with her parents but was raised by her grandmother, whom she describes as an elegant, Victorian-like lady who taught her about the finer things. Her grandfather died when she was very young, and Roldán-de-Moras would often wander through her grandparents’ house, open her grandfather’s closet door, and turn on the lights. Her memory of him was kindness and candy, but the closet illuminated a different side to him: the charro.

“I could see all the belts and the buckles and the hats and his outfits,” she says. “All of the Western wear. I did not really realize the importance of what he did until later, but I understood he was a charro at heart.”

Spirit of San Antonio | Oil on Linen | 30 x 40 inches

Roldán-de-Moras loved art from an early age, attending field trips to museums and taking note of paintings whenever she came across them. Her uncle was an artist, and when she was in middle school, she would visit his studio and dream. “I was just in awe,” she says. “I used to ask my parents, please put me in art classes. My dad appreciated art very much but was not into promoting the arts as a career. He had the idea that art was not for the intellectual, and I had promised to have some intellect.”

That promise led her, at age 16, to get a scholarship to medical school, focusing on plastic surgery and putting her artistic energy into wax models and embryo drawings.

For a while, she stuck to this path. When she realized medicine was not what she wanted to do, she moved to the U.S. to study biology at the University of Texas, now with a husband and her first child. Eventually, with encouragement from her husband, she left school and began to paint. It would take selling pieces for $100 at thrift shops before bigger sales and awards pushed her into the view of galleries and collectors.

Jarochas | Oil on Linen | 48 x 36 inches

As an adult, Roldán-de-Moras also learned that her grandfather was a driving force in convincing the Mexican government to officially recognize charrería as the national sport in 1933. Her determination to understand her subject matter is personal. She knows a mariachi from a charro and understands the escaramuza dress codes. Her technical skill around this knowledge and the breathtaking execution of its beauty is what hooks the attention of museums and galleries.

“This aspect of growing up in, understanding, and living the culture has a long history in the depiction of Western art,” says Emily Wilson, curator at the Briscoe Western Art Museum in San Antonio. “With Gladys, she is drawn to the escaramuza’s display of female strength and beauty, which shows itself in her comfort with the rules of the sport, the formalities and intricacies of the performance, and the difficulties of perfecting the moves. And her knowledge of the skills of horsemanship aid in her choice of models and in her depictions of both horse and rider in motion and at rest.”

Roldán-de-Moras doesn’t just sit down and start painting; she studies the subjects in a multitude of ways. With charrería, she attends events and photographs the action from the sidelines, bringing along her pochade box to make color sketches en plein air, getting the tones she wants, re-creating the light, sky, dirt, reflections, and the colors of the charro outfits. She takes these photographs and color notes — stunning versions of dusty French pink, azure, and ochre — back to her studio where she can dive deeper into a full painting, always listening to music, which she says is where many of her painting visions come from.

The Visit | Oil on Linen | 40 x 30 inches

“Gladys has a gift for capturing the folds and translucency of the fabrics in these elaborate outfits,” says Elizabeth Harris, owner and director of InSight Gallery in Fredericksburg, Texas. “The intricate regalia involved in the pageantry of the charreadas, the bullfighters, and even flamenco dancers are all brought to life by her brush. She is painting something not only that she knows but something she has a passion for.”

Roldán-de-Moras is also an advocate for the sport. While charrería has major sponsors in Mexico, the competitions in the U.S. have a more do-it-yourself feel, holding tamale and bake sales for funding. Roldán-de-Moras sometimes gets calls to fund new escaramuza dresses, which she loves to do.

“I think what she’s doing with her art and with the relationships she has with some of these teams is to build awareness and support here in the U.S. where the sport is still popular and important and culturally significant,” says Johanna Blume, curator of Western Art, History, and Culture at the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana. “Not just support for the sport, but for these girls. And she’s able to convey all of that in oil paint — to show the athleticism of these young women on their horses, in movement, with their skirts flying.”

Compañeros | Oil on Linen | 36 x 24 inches

Early in her career as a painter, Roldán-de-Moras brought her pochade box and camera down to the arena to attend an escaramuza event. She was excited and full of anticipation. But it was a hot day, and sitting there for a few hours began to take its toll. “I almost fainted,” she says, laughing. “I felt so silly because here I am, and I just have a camera. And here are these girls on these huge horses with these huge dresses, with these hats — and they’re competing. And they don’t faint.”

In the end, nearly fainting paid off. Roldán-de-Moras submitted the final painting from that day to the American Impressionist Society, and it won Best of Show 2013.

That was a turning point for her, she says. Her father used to come to her studio and encourage her to go back to medicine, but after that award, just a couple years before he died, he changed his tune. He told her, “I know what you were born for: to be an artist.”

Two years ago, Roldán-de-Moras attended a Zoom call that happened to include the medical director who had given her the scholarship. Her guilt for leaving was instantly assuaged when he told her that he was glad she left, otherwise she would not be the artist she is today. If there was any concern remaining that her intellectual life would be destroyed for her artistic dreams, Roldán-de-Moras’ studio is the perfect counterpoint. Inside the elegant space, she has made room for a renaissance lifestyle.

“When you visit her studio, you will find mannequins displaying vintage outfits and she can tell you the history behind each one, often from her family in Mexico,” Harris says. “Piles of books and other historical reference material are intermixed in a space where her son, a professional opera singer, and her husband, a talented musician, often gather others to sharpen their respective crafts. The space itself exudes creativity in so many forms that you hope that just by being there, you’ll soak up some of the natural talent that runs through her family. That talent, however hereditary, is honed by meticulous research, practice, and study.”

Matador | Oil on Linen | 40 x 30 inches

At one point in her life, Roldán-de-Moras dreamed of being an escaramuza, but now, she keeps the tradition alive by painting it. At the moment, she can’t paint fast enough to meet the demand of her galleries and collectors, and she is extremely humble about this fact. She knows she’s arrived, but she doesn’t take it for granted. For her, it’s perseverance, not fate, that got her here. And also the decision to embrace her identity and charro family history.

“A mentor once told me to find my voice,” she recalls. “He said, ‘Just paint what you love, and it will happen,’ And it really did. I started to paint what I knew. But I didn’t find it; I think it found me. And I just hope that the Mexican people, especially, are proud that I did represent them the way that they should be represented — with true respect.”

No Comments