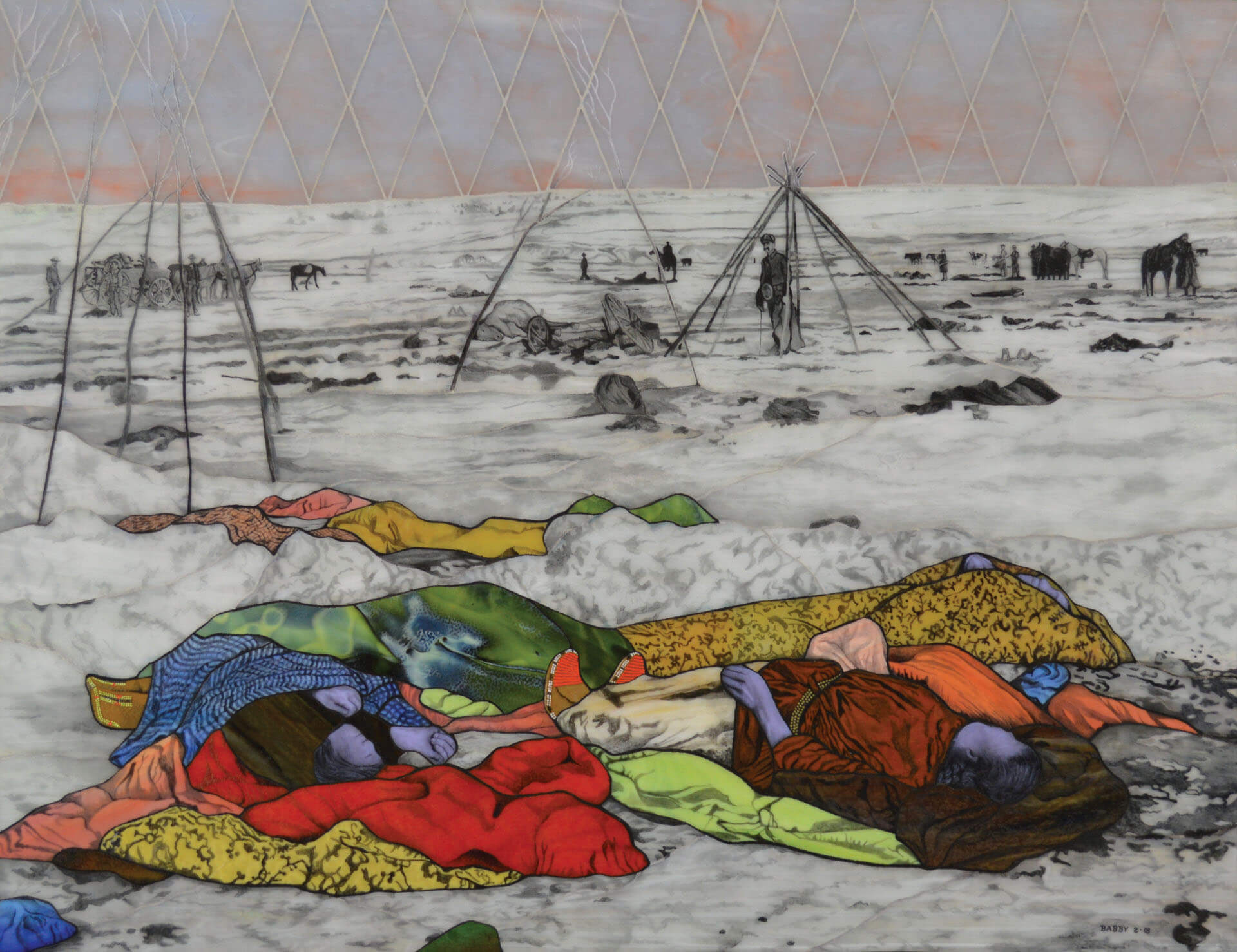

03 Jan Hope and Beauty

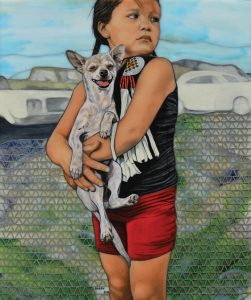

When people encounter Angela Babby’s work from a distance, they often think they’re viewing oil paintings. But, as they draw closer, they discover the vibrant images are intricate, enameled glass mosaics. “Glass contains light,” the artist explains from her home in Billings, Montana. “When I depict a person from the past in glass, it has a three-dimensional depth that I could never achieve with paint.”

Many of Babby’s mosaics are based on black and white photographs of her Lakota ancestors or other tribal Nations indigenous to the U.S. She chooses subjects that speak to her: through a personality that’s conveyed, a shared cultural history, or a meaningful story.

The mosaics require a labor-intensive process with many technical steps. The 28-by-38-inch Love is Love, for example, took almost two months. “Each piece of the mosaic was ‘painted’ and fired four times to make it appear how I wanted,” Babby says, noting that this is the only mosaic she’s created based on a painting, Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss.

Love is Love | Kiln-fired Vitreous Enamel on Glass Mosaic on Tile Board | 28 x 38 inches | 2015

To make her mosaics, Babby has mastered three mediums: stained glass, vitreous enamel, and tile. After drawing and configuring her composition, she cuts and grinds each piece of glass by hand to form the image. She then paints details on the glass with vitreous enamel, which she mixes from powdered glass and a medium. Each of these painted components is slowly fired in a kiln at more than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit. This process often occurs multiple times, fusing the layered glass elements. The final steps are adhering each of the pieces down and applying a tinted mortar, which is the first time she sees her work come together.

Babby’s work appears in Clearly Indigenous: Native Visions Reimagined, which opened at Santa Fe’s Museum of Arts & Culture in 2021 and is touring the U.S. through 2027. Sponsored by the International Arts & Artists, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit dedicated to increasing cross-cultural understanding and exposure to the arts, the exhibit is at the Cincinnati Art Museum through April 7. Visit artsandartists.org for other dates and additional information.

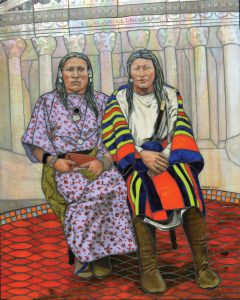

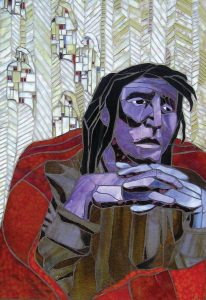

Chief Pute (Jhon’s Grandfather) | iln-fired Vitreous Enamel on Glass Mosaic on Tile Board | 14 x 18 inches | 2020

In this Q&A, Babby shares more about her life and work. Ultimately, she hopes her mosaics impart two ideas: “hope and beauty.”

WA&A: Why did you choose mosaics?

Angela Babby: My evolution to glass mosaic happened quickly after participating in my first Native American art market in 2002 at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. I got into the market on my first try and didn’t have many artworks. My main mediums at that time were watercolor and acrylic.

Before moving to Phoenix, I had worked at a stained-glass factory in Portland, Oregon. I had a huge cache of glass stored in my shed. After getting rained on at that first market and reframing many artworks, I thought, ‘If you intend to keep doing shows, you must pursue a waterproof medium.’

I started to teach myself kiln-fired enameling on glass shortly after making my first figurative piece. I wanted to be able to bring more detail into my mosaics, but this process took 10 years to master.

WA&A: What was your first creation that sparked your desire to create more?

Supreme Respect for the Two Spirits | Kiln-fired Vitreous Enameled Glass Mosaic on Tile Board | 16 x 20 inches | 2013

A.B.: My first artwork was inspired by the very sad picture of Chief Medicine Bottle, who was one of 38 plus 2 hanged in the largest mass execution in American history at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, in 1862. “Plus 2” refers to the executions of leaders Sakpedan (Little Six) and Wakan Ozanzan (Medicine Bottle) at Fort Snelling in 1864. His face seemed to embody all of the pain and sadness of Native Americans.

The piece did not have any enameling, and it sparked my desire to teach myself enameling to better capture his expression. This picture and this event have recurred many times in my work.

When I took it to markets, people did not like it. One lady came around a corner and jumped back, saying, ‘Oh, it’s Indian Frankenstein!’

It took five years, but it ended up selling to the Aktá Lakota Museum & Cultural Center in Chamberlain, South Dakota. It was a valuable lesson for me.

WA&A: What is it like to work with your materials?

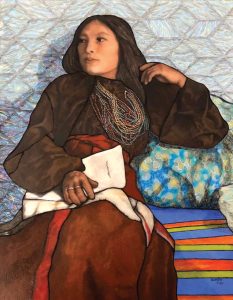

Zitkala sa: Why I am a pagan | Kiln-fired Vitreous Enamel on Glass Mosaic on Tile Board | 14 x 18 inches | 2021

A.B.: The whole reason why glass fascinates me is that you can’t really control it. It does what it wants to, and you can only guess what it will do. I got frustrated with painting because it seemed like it would never truly be done; you could always find something wrong. Glass makes you stop. At some point, you say, ‘That’s the best I can do.’ And once there, you can’t go back.

Enamel has many different, very subtle quirks. Red, for example, burns away quite easily unless you manage both the amount of enamel you apply and the temperature. To understand how the colors change when fired, you must create test strips of your mixes and fire them. I have found many workarounds through trial and error to create the details that a specific piece needs to express the message I’m trying to convey.

My favorite part is that you don’t know what it will finally look like until the very last step. The glass itself brings other dimensions and color interactions.

After that, there are still two labor-intensive steps: adhering it down and applying mortar. By then, you can barely see it without hating it. It can take up to a year to start liking what I’ve done because it was so time-consuming and detailed to make.

Love Trumps Hate | Kiln-fired Vitreous Enamel on Glass Mosaic on Tile Board | 20 x 24 inches | 2016

WA&A: How is your life history and personality reflected in your work?

A.B.: I grew up crisscrossing America, living on different reservations, never my own, and feeling like I didn’t belong. I never knew a professional artist, and the way that I was raised, it was not something that I considered.

I studied everything else in college before finding art. I created my own successful decorative painting business, and because of burnout from running it, I took a pottery class. A fellow student saw what I was doing and said, ‘Wow, that’s really great! You should apply for the Heard Market!’

That chance comment is what got me to apply. I had never been to an Indian market until I was in one. There were many people like me, including relatives I had never met at that market. I was very shy, but doing public markets has caused me to be fairly confident speaking about my art.

As I started showing my work, my dad was writing a book on our genealogy with my cousin. We were taken to the graveyard at the Red Cloud School on the [Pine Ridge Reservation] many times as kids, and we knew we were related to Chief Red Cloud, but as youngsters living off the res [in the Pacific Northwest], we didn’t really care. My dad wrote the book so that people could find all of his painstakingly compiled information. The pictures in that book also started to reveal people and history to me.

Medicine Bottle | Art Glass Mosaic on Masonite | 19.5 x 13.5 inches | 2002

WA&A: What are some of your biggest influences and motivations as an artist?

A.B.: I am influenced by emotion and color. I love Gustav Klimt’s images because they are not realistic but find a way to connect directly to your inner self. He used figurative work to deal with love, fear, and death in a way that I admire and want to understand. I feel more like a scientist. I’m trying to figure out all the different ways to create images that inspire or affect the viewer because the beauty of the glass can bring you in to consider what’s being said in a way that paint doesn’t always do.

WA&A: What do you think the role of an artist is in society?

A.B.: It’s an individual thing. Great artists communicate with people and make our lives worth living. The wonder of our world is something humans need, and art has always been used to communicate the finest things in life, like nature, landscape, and beauty, but also tell the stories of our hardships and express emotions. By doing this through visual images, there is a sense of saying something in silence, where a person can find something to relate to on their own. They should not need to be told what it means.

No Comments