03 Jan ARTIST SPOTLIGHTS: JESSE LITTLEBIRD

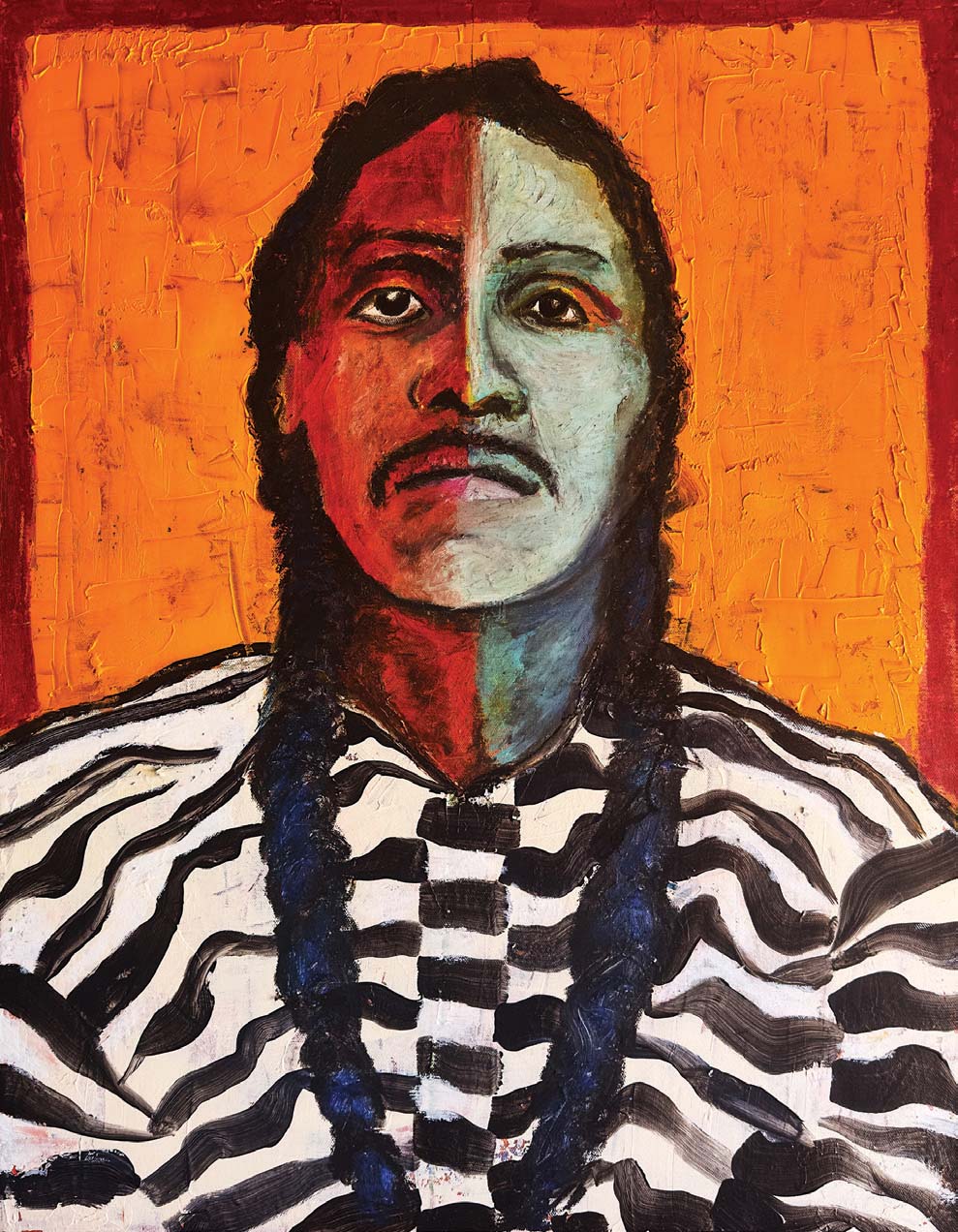

Jesse Littlebird’s joyfully provocative paintings remind some viewers of urban street murals. Still others note the undeniable influence of his Indigenous Southwestern heritage, evident in tribal figures, symbols, and patterns. Those with a taste for subversion might also savor his appropriate approach, championed by 20th-century masters from Dadaist Marcel Duchamp to Pop pioneer Andy Warhol, boldly altering existing imagery to make incisive social or political points — what French critics call détournement, literally “hijacking.”

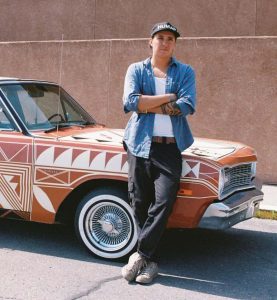

The multitude of messages in the 32-year-old, Albuquerque-based artist’s creative output speaks most of all to his wide-ranging interests and aspirations. That’s not to mention the prodigious talents nurtured by his parents, graphic designer Deborah Littlebird and the respected Pueblo painter, storyteller, writer, filmmaker, and actor Larry Littlebird. “My dad is a Renaissance man,” Littlebird says. “We traveled around in a multicultural theater troupe, doing retreats, counseling, and community healing. Oral traditions and storytelling are at the heart of my whole outlook on life. My art has a narrative, sometimes political, even revolutionary spirit.”

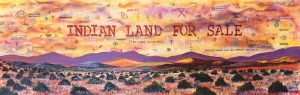

Indian Land for Sale | Aerosol, Marker, and Oil Stick on Canvas | 32 x 84 inches | 2024

Such a richly eclectic background encouraged Littlebird to explore a wide range of creative forms. At Albuquerque’s Volcano Vista High School, he found art teacher Peggy Trigg’s classroom “a sanctuary.” After graduating, he studied photography and filmmaking at the University of New Mexico, then worked as a production assistant on such local projects as director Denis Villeneuve’s 2015 crime thriller “Sicario.” In 2017, he went on to participate in the Indigenous Film Program at Sundance Institute, and then spent time in Los Angeles doing writing and photography. “But I got frustrated and disillusioned with how long of a process it is to make something right in the film industry,” he says. So, later that year, Littlebird came home to Albuquerque and began painting. “My friend Rocky Norton, an amazing painter, shared with me how to make big canvases on a relatively small budget, and everything started snowballing. When the pandemic hit, I became a full-time artist.”

Littlebird’s paintings resonate with collectors who appreciate their lively compositions, vibrant colors, and provocative messages. In the vast panoramic desert landscape emblazoned with its own title, Indian Land for Sale, he says, “I’m asserting that I’m an Indian painting land that doesn’t belong to me and never belonged to anyone.” His reimagining of a 1901 photograph depicting a Native prisoner before his braids were shorn jars viewers into deep sympathy by portraying its somber subject in bright pop colors.

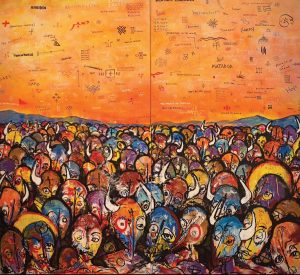

Enlightened Buffalo Souls Emerging from Where the Light Lives | Mixed Media on Panel | 96 x 96 inches | 2022

In these and myriad other ways, Littlebird continues his family tradition of sharing the true stories of his people. Now, he’s broadening his reach through the recent opening of his own exhibition space in Albuquerque, Kukani Gallery, which is named after the Laguna Keresan word for “red.” Says the artist-gallerist, “When you sell a painting, it feels like winning the lottery. I’ve been having some success now, and I want to give it back to emerging artists so they can have their own successes.”

Littlebird is represented by Blue Rain Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Durango, Colorado; he’s included in the Santa Fe location’s group show Voices of the Land: Contemporary Native Expressions from February 28 to March 11. Also see his work at Kukani Gallery in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Based in Marin County, California, Norman Kolpas is the author of more than 40 books and hundreds of articles. He also teaches nonfiction writing in The Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension.

No Comments