03 Jan PERSPECTIVE: A COWBOY ARTIST WITH LIMITLESS RANGE

Harry Jackson, the artist credited with revitalizing Western American bronze beginning in the late 1950s, reviving the lost art of polychrome sculpture, and writing a definitive book on Italian Renaissance lost-wax bronze casting, is also the man who, in an authentic cowboy voice, could sing about the life of a chuckwagon cook: “I sort all the big stones right out of the beans, and I don’t wipe the fryin’ pans off on my jeans.” He was friends with both Jackson Pollock and John Wayne. He was admired as an Abstract Expressionist painter, then celebrated for his realist paintings and sculptures, and later combined genres in works that fit no single artistic box. Three presidents displayed his work in the White House, and it hangs in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., among numerous other renowned institutions around the world.

But, as Jackson’s grandmother once told him, he was so contrary that he could “float upstream,” defying the current. When he was honored with an exhibition at a Wyoming museum, Jackson decided he wanted to see the show after hours one night. So he pulled out a pistol and shot the lock off the door. “That was Harry,” says art historian Dr. Henry Adams with a wry smile.

Adams, the Ruth Coulter Heede Professor of Art History at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, describes the artist as “a curious mix of charming and irascible.” He has also been called complicated, a genius, cantankerous, and generous in sharing his artistic knowledge. He was a colorful figure who lived large. Especially in his younger years, he was “unfettered by shyness,” remembers Sue Simpson Gallagher, owner of Simpson Gallagher Gallery in Cody. Jackson met Simpson Gallagher’s grandparents soon after he moved to Wyoming in 1938, and the two families remained close throughout the artist’s life. Simpson Gallagher has represented his work for most of the 30 years since she opened the gallery.

Washakie II | Painted Bronze | 20 x 15 x 6 inches | 1981 | ©Harry Jackson, Booth Western Art Museum Permanent Collection, Cartersville, GA

While Jackson made friends widely and easily, he could also put people off, the result of a headstrong personality combined with mood disorders, PTSD, and seizures, which he suffered after being seriously injured during one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific during World War II. Perhaps in an attempt to compensate for those disabilities, he demonstrated a tremendous drive, Adams says. “It’s extraordinary that he did so much in spite of everything.” Simpson Gallagher adds that Jackson “was curious and loved to challenge himself. There was nothing about Harry that was stagnant. I’m pretty sure he was a mercurial creature before his injuries — not just ups and downs but all over the place.”

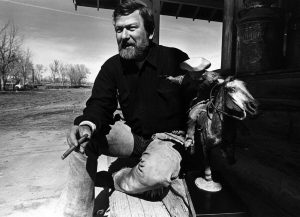

Artist Harry Jackson, pictured here in 1972 with his artwork Pony Express Painted.

The first place that tugged hard on Jackson’s curiosity as a boy was the West. Growing up in Chicago, he admired the cowboys he met at the Union Stock Yards, where his mother owned a lunchroom. In 1937, when he was 13, a Life magazine photo spread on cowboys in Wyoming reinforced his fascination, and at 14, he ran away from home and hitchhiked to Wyoming. Soon he was working on the Pitchfork Ranch near Meeteetse. Yet, every winter for several years, he returned to Chicago to study art at the Chicago Academy for the Arts and the Art Institute of Chicago, where he had taken classes as a boy. Today, many of Jackson’s childhood drawings, on napkins and paper menus, are preserved as part of an extensive collection at the Cody-based Harry Jackson Institute, which in 2018 was gifted more than 5,000 works from the artist’s estate. “It was probably the largest single gift of artworks in the history of Wyoming,” says the institute’s president and CEO, Mark Harris. The organization is in the process of conserving and cataloging the collection for display, with a plan to loan it to other institutions for exhibitions.

When he was 18, Jackson enlisted in the Fifth Marine Amphibious Corps and, in November 1943, took part in the Battle of Tarawa, one of the Pacific’s bloodiest assaults. He witnessed the deaths of countless fellow Marines and was severely wounded, for which he received two Purple Hearts. At age 20, he was stationed in Los Angeles as the Marine Corps’ youngest-ever combat artist. There, he made pencil-and-ink drawings that were signed and often came with accompanying notes, providing glimpses of day-to-day military life and combat.

Stampede | 1965 | Oil | 120 x 252 inches | ©HJ Trust 1980

In Los Angeles, Jackson encountered the Jackson Pollock painting that set him on a radically different artistic path. As he wrote in his journal at the time, “I was bowled over by Pollock’s 1943 Abstract Expressionist painting The Moon Woman Cuts the Circle … That single artwork caused me to relive Tarawa’s bloody butchery; I knew that I had to meet Pollock face to face ASAP.”

With an honorable discharge from the Marines, he moved to New York City, met and became friends with Pollock, and quickly began experimenting with Abstract Expressionism. His journal notes, “A few days after Jack and I bonded, my wild White Figure painting volcanically erupted from my sealed-off, blacked-out mind.”

Cosmos | 1996 | Bronze with Fat Egg Tempera Paint | 18 x 45 x 15 inches | Photographed by Marcello Berton, ©HJ Trust 1980

Jackson’s Abstract Expressionist paintings quickly caught the attention of influential critic Clement Greenberg and others, and for three years, they were exhibited in a New York gallery. Meanwhile, he met and was briefly married to the Abstract Expressionist painter Grace Hartigan. (He was married at least four times.) Before long, however, he decided that the style was “too removed from man.” It didn’t touch on the lives of ordinary people like the cowboys he knew in Wyoming. Inspired by travels in Europe in the 1950s, he returned to realism, a move that Life magazine in a 1956 profile titled, “Painter striving to find himself: Harry Jackson turns to the hard way.”

Indeed, Jackson proved unafraid of hard work. In Italy, initially on a Fulbright scholarship, he studied Renaissance lost-wax bronze casting techniques that had been passed on from father to son for generations but were rarely written down. “He was passionate about authenticity,” Simpson Gallagher recalls. To that end, and to control the quality of every step in the bronze casting process, the sculptor established his own foundry in Italy, and later one in Wyoming. He made important innovations to the lost-wax process.

Sacajawea with Packhorse | 1992 | Bronze with Acrylic Paint | 27 x 20 x 14 inches | ©HJ Trust 2012

Jackson was also a pioneer in reintroducing the use of paint on bronze, an ancient technique employed by the Romans and Greeks, but which had been virtually lost. In some cases Jackson’s colors added to the sculpture’s realism. These pieces became the inspiration for exquisitely painted bronzes by the late American sculptor Dave McGary, who worked for Jackson in Italy. In Jackson’s much-later multi-figured bronze version of his monumental painting The Stampede, his wild, seemingly random application of paint harkens back to Abstract Expressionism.

“Harry was a colorist; he gained interest in color through the Old Masters,” says Cody-based Western sculptor Gerald Anthony Shippen. Jackson hired Shippen as a young artist in 1977 to paint bronzes in his studio in Italy, and the two remained close. Especially with sculpture — such as the painted stampede piece Cosmos — he “was trying to make sculptures into 3D paintings. It was 2D realism stretched and pulled into another dimension,” Shippen says.

With many of his bronzes, Jackson created multiple versions over the years. He was especially drawn to the figure of Sacagawea, which he produced in a number of poses and sizes. Simpson Gallagher describes a personal favorite of hers, Sacajawea with Packhorse, as a “strong woman, focused in her gaze. She’s a force, and you can feel it.” Shippen recalls that at one point, Jackson envisioned a more than 300-foot-tall Sacagawea to be installed on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. Arnold Schwarzenegger, California governor at the time, loved the idea, but even with passion and drive, the artist couldn’t make it happen.

The Flag Bearer | Painted Bronze | 29.12 x 36 x 10.25 inches | 1983 | ©Harry Jackson, Booth Western Art Museum Permanent Collection, Cartersville, GA

Jackson returned to a more expressionist approach in later paintings based on his combat experiences. Among these were several versions of a powerful image featuring an abstracted figure — green to represent all warriors — being shot from multiple angles. The soldier was a close friend of Jackson’s who was killed at the same moment that mortar hit the back of the artist’s head. Describing the work in the 2021 Wyoming PBS documentary “Harry Jackson’s Wyoming Story,” conservator Rebecca Weed notes that Jackson experienced the painting as cathartic. “It opened up a lot for him,” Weed says.

Jackson’s self-expression in multiple mediums extended beyond the fine art world. He did a stint as a radio announcer, voiced the narration for a documentary film about WWII, and sang and recorded cowboy songs he learned on the Pitchfork Ranch. In early 1960s New York, he hung out and sang informally with Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, and painted a portrait of Dylan. He also produced a bronze of John Wayne, whom he described as “a wonderful embodiment of the timeless strength of the rugged individualist, the one-man majority I believe in with my entire being.”

“It was a crazy life, rough and tumble but also very intellectual,” Adams says of the artist. “What’s interesting to me is the way Harry stepped into the mythic roles of manhood in that period: cowboy, soldier, Abstract Expressionist, businessman, and friends with an amazing range of people. It’s a life that illuminates a lot of both the ideals and tensions of the 20th century.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written for national and regional magazines, newspapers, museums, and galleries, has served as a book and magazine editor, and is the author of four books on visual artists; gussiefauntleroy.com.

No Comments