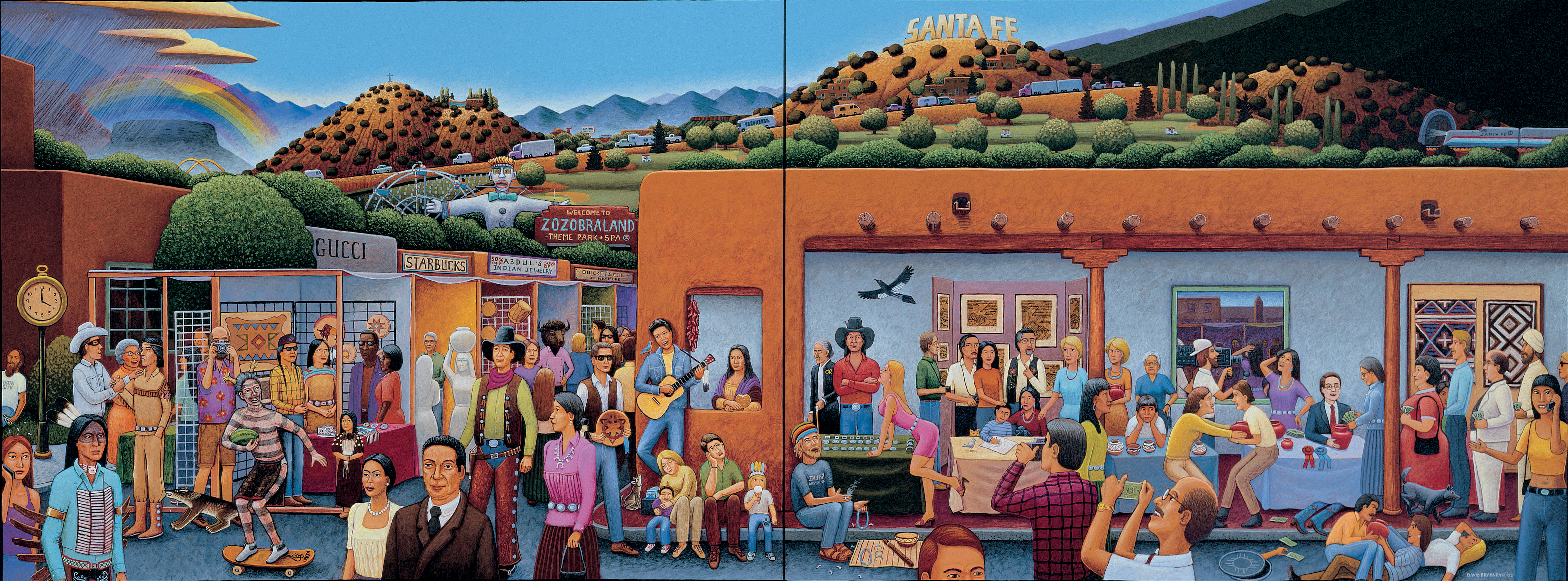

15 Jan The Storyteller

A RECENT RETROSPECTIVE AT THE AUTRY MUSEUM of the American West in Los Angeles brought out the enthusiasm that made artist David Bradley’s work iconic among audiences. “Visitors let out gasps or painful giggles. They started conversations among themselves about stuff they never would have thought about,” says Karen Merman, a docent at the museum. “I was taken by the amount of time that people just stood and looked.” The exhibit showcased 40 years of the artist’s career and opened in 2015 at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, ending this January at the Autry.

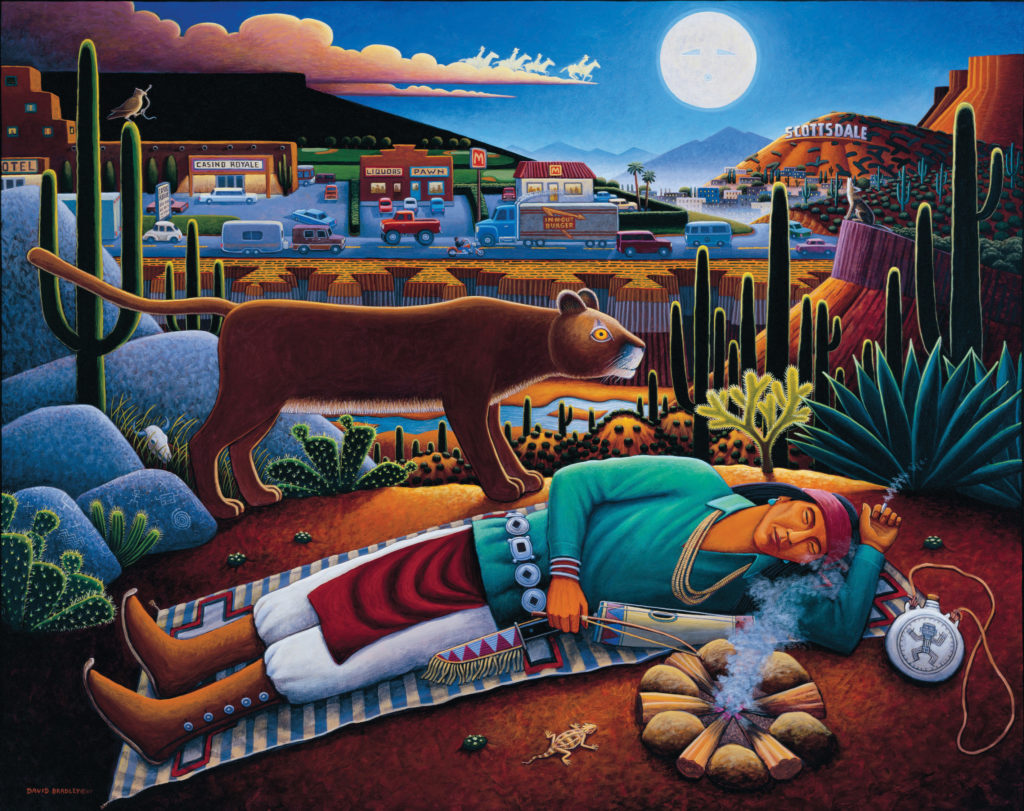

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream | Acrylic on Canvas | 60 x 76 inches | 2005 Gift of Richard E. Nelson, Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian

Inspiring these types of reactions and conversations is exactly what Bradley set out to do as a Minnesota Chippewa artist and activist. Influenced by Pop Art, traditional Native American narrative painting, and other facets of art history, Bradley works to dispel the myths and stereotypes imposed on American Indians, and to highlight the commodification of his culture. His work addresses issues surrounding identity, cultural appropriation, capitalism, and social justice.

“I am a storyteller of sorts. Much of it has layers of meaning. Sometimes there were cryptic, secret references,” says Bradley. “To be an artist is to seek the truth. I usually have a narrative in mind when I start a piece, but I always put in more as I go.”

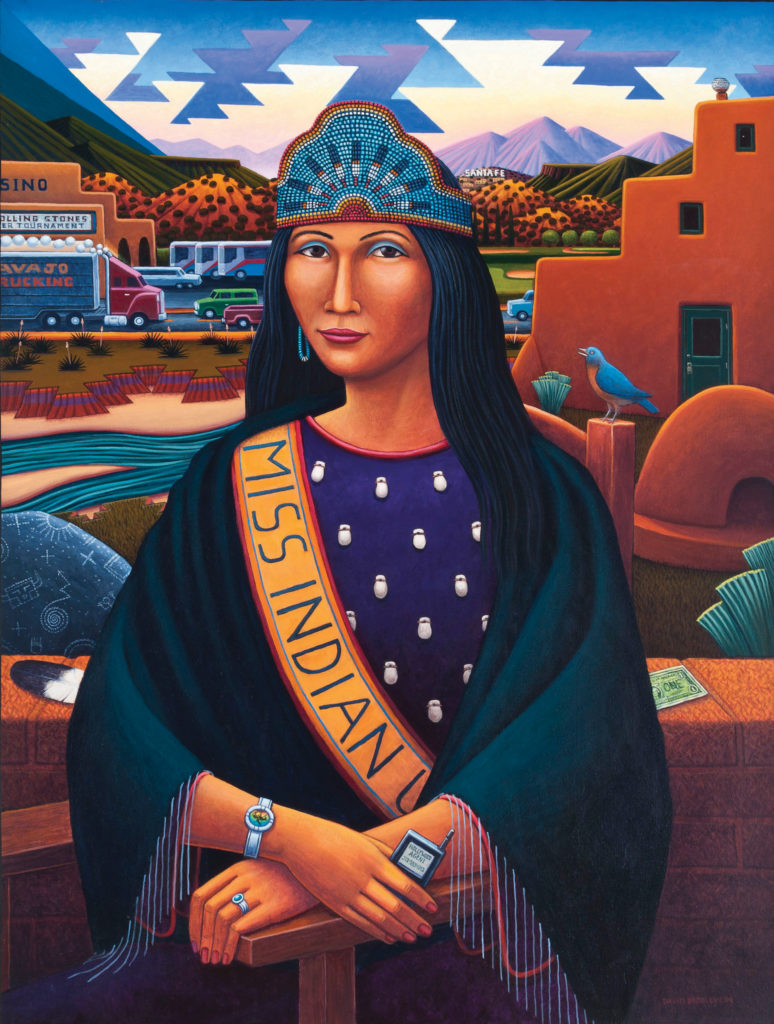

Pow Wow Princess, Southwest | Acrylic on Canvas | 48 x 36 inches | 2009 Museum Purchase, Museum of Indian Arts & Culture; 59073

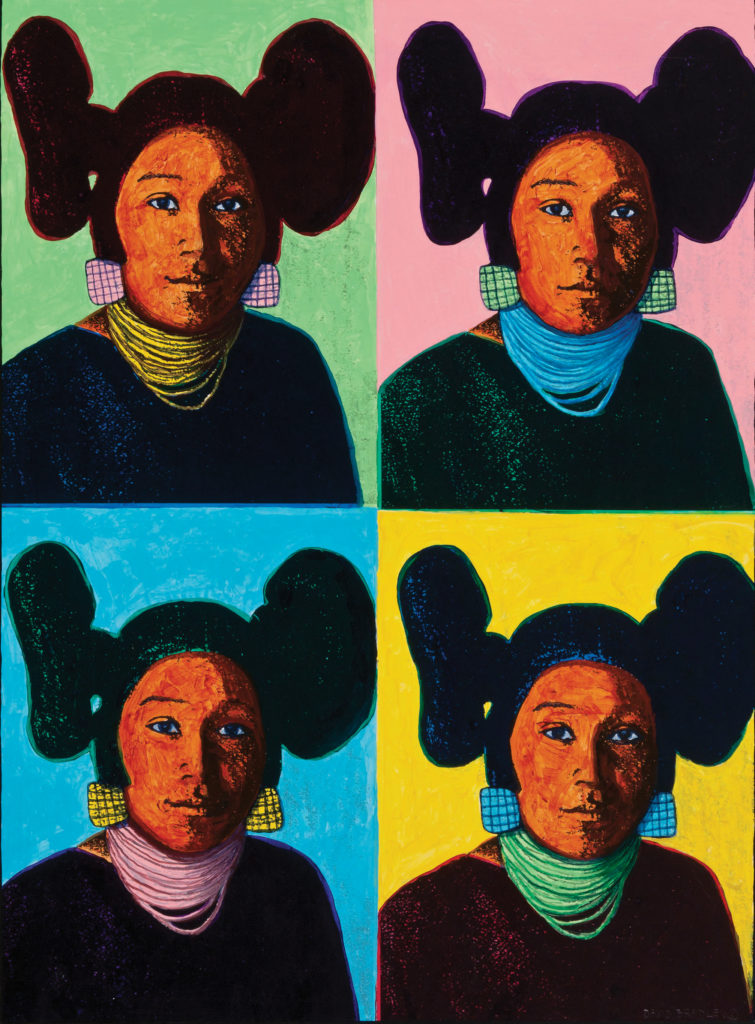

As a part of this effort, Bradley will also parody historical artworks, re-positioning them within a Native American perspective of the contemporary Southwest. In Pow Wow Princess, Southwest (2009), Miss Native American USA is posed like the Mona Lisa. And in O’Keeffe After Whistler (2007), Georgia O’Keeffe stands in for Whistler’s mother. The artist has also completed multiple interpretations of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, including one featuring Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Hopi Maidens (2012), meanwhile, pays homage to Andy Warhol, swapping Marilyn Monroe’s blonde hair for Hopi “butterfly” buns.

“Bradley’s work really speaks to the superficiality of market-based imagery,” says Amy Scott, the Autry Museum’s executive vice president of research and interpretation. “His use of icons, such as Diego and Frida, causes us to think about the quantification and the absurdity of the art market. … Bradley was the first to call it out.”

Beyond his paintings and sculptures, Bradley is also recognized for his efforts to expose the multimillion-dollar industry surrounding counterfeit arts and crafts passed off as authentic Native American works. His activism helped bring the conversations surrounding the issue into the national spotlight, resulting in the passage of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, which stiffened penalties for illegally misrepresenting an item as Native American-made — a practice outlawed in 1935, though the counterfeit market continues today.

Hopi Maiden | Wood and Bronze with Patinas | Edition of 12 2000 | 16 x 15 x 8 inches | Museum Purchase, Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, 59072

“For over 500 years, Indian people have had our land and nearly everything else stolen from us,” Bradley told Pasatiempo magazine in 2015. “Now that Indian identity has become a very marketable commodity, they want to steal that from us, too. I was one of the few who stood up and said, ‘No! We are not going to lay down and let that happen.’”

Born in Eureka, California, in 1954 to a Minnesota Chippewa mother and an Anglo father, Bradley was taken from his family and raised in foster care, a situation common before the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. Most of his childhood was spent on the White Earth Ojibwe Reservation in Chippewa, Minnesota, and in Minneapolis. On his own by age 16, Bradley finished high school with the help of friends and left to find his place in the world. He spent two years at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota before taking a break from school and joining the Peace Corps, where he lived in Guatemala with Mayan Indians. The experience led Bradley to “a new life outlook, ‘an experience with essentials,’ that allowed him to better understand his heritage and ‘changed him forever,’” according to the history provided by Blue Rain Gallery, the artist’s representing gallery in Santa Fe.

Tonto and the Lone Ranger | Bronze with Patina | Edition of 12 | 2014 12.75 x 9.25 x 5.5 inches (Tonto), 15 x 15 x 9.5 inches

(Lone Ranger) | Collection of the Artist

After returning from the Peace Corps, Bradley was drawn to the Southwest and attended the Institute of American Indian Arts, where he graduated first in his class with a Bachelor of Fine Arts. He also studied at the University of Arizona and the College of Santa Fe.

“He is such a huge influence over the Native arts scene, both in his beautiful representations and in his political commentary,” says Amanda Crocker, marketing director for the Santa Fe Indian Market.

In August 2011, Bradley was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease, but despite the inability to paint, he still finds ways to tell stories. There’s another book project in the works, and his work will appear in the Santa Fe Wheelwright Museum’s Laughter and Resilience: Humor in Native American Art, on exhibit through October 2020. Bradley’s work has appeared in museums throughout the country, including the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, and the New Mexico Museum of Art in Albuquerque, among many others. He’s received numerous honors and fellowships, including recognition as the only artist to win the top awards in both painting and sculpture at the Santa Fe Indian Market.

Hopi Maidens | Mixed Media on Panel | 40 x 30 inches | 2012 Museum Purchase, Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, 58603

“He was part of a group of artists that pushed contemporary Native American art beyond the infographic and traditional, sort of laying the foundation for much of what’s going on now,” says Scott. ”In many ways, Bradley and [Harry] Fonseca have opened doors that the younger artists walked through — or were born on the other side of.”

As an artist, Bradley wanted to tell real stories versus those imagined, to illuminate instead of showcase. His art will carry his vision forward long into the future, empowering countless other generations of artists and encouraging his audience to think.

No Comments