11 Jan A Shared Passion

At rare moments in the art world, the planets seem to align, bringing together a theme, a setting, a celebration-worthy occasion, and an artist or benefactor in an exhibition of singular distinction. Such occasions all but demand that art lovers drop everything and make travel plans — or, if leaving home isn’t possible, set aside time for traveling virtually — so they can fully take in a satisfying aesthetic experience.

Sandy Scott, Heart Dog | Bronze | 9 x 8 x 8 inches Collection of Sandy Scott

Just such a show, titled Wild World: 200 Years of Nature in Art, debuts on February 27 at Brookgreen Gardens. The fabled 9,127-acre sculpture garden and wildlife preserve — which celebrates its 90th anniversary this year — unfolds in the South Carolina Lowcountry at Murrells Inlet, about 80 miles up the coast from Charleston. Set on four historic rice plantations that were purchased in 1931 and were opened the following year by transcontinental railroad heir and philanthropist Archer Huntington and his wife Anna Hyatt Huntington, one of the most prominent figurative sculptors of her time, the idyllic location was originally dedicated to showcasing Anna’s works and those of other American sculptors amidst its lush landscape. Over the years, that collection has grown to almost 3,000 pieces, about 500 of which are displayed outdoors, and Brookgreen’s exceptional combination of nature and art earned it recognition as a National Historic Landmark in 1992.

- Sandy Scott, Rainbow Trout, Trail Creek | Watercolor | 5 x 7 inches | Collection of Sandy Scott

- Dennis Anderson, Elk | Acrylic | 18 x 24 inches | Collection of Sandy Scott

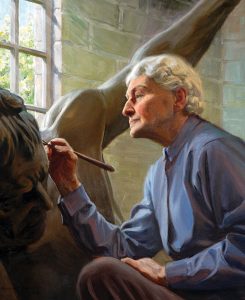

Artist Sandy Scott first felt compelled to make the pilgrimage to Brookgreen almost 40 years ago. Now acclaimed as one of America’s greatest living sculptors of wild and domestic animals, at the time the Oklahoma native had only just begun to explore sculpture after already establishing a solid reputation for her limited-edition etchings.

“I’d heard about Brookgreen ever since my days at the Kansas City Art Institute,” Scott says. “I finally decided to take a trip there, driving my motorhome from Texas, where I was living at the time. I was just going to visit for maybe three days. Well, I wound up spending three weeks there, and by the time I left, I’d practically memorized everything about Brookgreen.”

- Daniel Chester French, Benediction | Bronze | 37.5 inches tall | Collection of Brookgreen Gardens

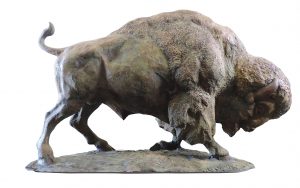

- Sandy Scott, American Icon | Bronze | 42 x 64 x 25 inches Collection of Brookgreen Gardens Gift of Trish Smith

Scott describes that first exploration as “pivotal and life-changing” in her career development. “I’d already been adding a little sculpture to my repertoire,” she says. But steeping herself in Brookgreen’s collection ultimately led her to change her medium, she explains. That’s not surprising, considering that she got to study not only 106 of Anna Hyatt Huntington’s inspiring works but also pieces by some 500 other American sculptors, including Western icon Frederic Remington, Daniel Chester French (of Lincoln Memorial fame), Beaux-Arts master Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and others, including Katharine Lane Weems, Gertrude K. Lathrop, Marilyn Newmark, and Paul Manship.

Herbert Bohnert, Anna Hyatt Huntington | Oil on Canvas | 29 x 24 inches | Collection of Brookgreen Gardens

Every few years that followed — during which time Scott moved to Loveland, Colorado, before eventually settling at the foothills of the Wind River Mountains in Lander, Wyoming — she returned to Brookgreen for fresh inspiration. Along the way, she developed a richly supportive working friendship with Robin Salmon, now Brookgreen’s vice president of collections and curator of sculpture.

In 1996, Brookgreen acquired Scott’s Peace Fountain, an 84-inch-tall bronze water feature depicting birds alighting on craggy branches. The sculpture is now on permanent display and is the first of six of her sculptures — the latest is American Icon a towering bronze of a bison — that Scott gifted to Brookgreen.

Sandy Scott, American Icon | Bronze | 42 x 64 x 25 inches Collection of Brookgreen Gardens Gift of Trish Smith

She began teaching workshops regularly in Brookgreen’s Master Sculptor Program, and her ties to the one-of-a-kind institution grew ever stronger when, in 2006, Scott says she “got a phone call from the chairman of Brookgreen’s board of trustees, inviting me to join them. I accepted.”

Sandy Scott went on to serve three consecutive four-year terms on the board. In the process, she conjectures, she helped Brookgreen broaden its scope to embrace more living artists and more sculptors from the West in its collection. “Sandy’s take on her role is spot-on,” says Salmon of that assessment. When Scott termed out of her board position a couple of years ago — and, she adds with a chuckle, “aged out, since I’m 77 now” — barely a heartbeat passed before the board invited her to become a life trustee. “I was just absolutely thrilled at that,” Scott adds. “It’s one of the biggest honors of my life.”

- Julie Jeppsen, Toby | Oil | 9 x 12 inches | Collection of Sandy Scott

- Julie Jeppsen, Mac | Oil | 9 x 12 inches | Collection of Sandy Scott

During her years on the board, Scott had already decided to bequeath Brookgreen her personal art collection. “I don’t have heirs,” she says matter-of-factly. “So I want as many people as possible to enjoy it.” The treasure trove stretches back to what she estimates at well over 300 outstanding etchings, drypoints, lithographs, and drawings that she began purchasing early in her career from top nature, wildlife, and sporting artists, such as Reinhold Palenske, Diana Thorne, Frank Benson, Hans Kleiber, and Rosa Bonheur. “They were really affordable when I was starting out,” she says. Also included are paintings by such notable artists as John Seerey-Lester, Dennis Anderson, Heiner Hertling, Sonya Terpening, and Bob Kuhn; not to mention portraits painted by Julie Jeppsen of Scott’s dogs Mac, a Scottish terrier, and Toby, a Westie. “This is a very personal collection Sandy developed over a long period of time, and it reflects her sensibilities as an artist,” says Salmon.

- Sonya Terpening, Summer Day | Oil | 10 x 12 inches | Collection of Sandy Scott

- Paul Manship, Owl | Gilt Bronze | 21 x 12 x 12 inches Collection of Brookgreen Gardens

- Anna Hyatt Huntington, Fighting Stallions | Aluminum | 180 x 144 x 76 inches Collection of Brookgreen Gardens

This all seems to come full circle with Wild World: 200 Years of Nature In Art, which opens February 27 in The Rosen Galleries at Brookgreen Gardens and runs through May 23. The exhibition kicks off the two-year celebration of the museum’s 90th anniversary, explains Salmon. And while many two-dimensional works and small indoor sculptures already in the institution’s collection are featured, Scott also sent a generous shipment of the aforementioned gifts to Brookgreen that will be on view, including her own early etching entitled Loon Call.

The event also marks the debut of The Rosen Galleries, an indoor exhibition space measuring close to 6,000 square feet. The galleries occupy a fully renovated former welcome center, built in 1994 in a contemporary interpretation of the brick buildings there, complete with exterior metalwork that, Salmon observes, is “a geometric abstraction of the Spanish moss” found on historic buildings on the grounds.

Laura Gardin Fraser, Pegasus | Granite | 183 x 183 x 92 inches Collection of Brookgreen Gardens

Although Brookgreen Gardens has been receiving visitors during the pandemic with appropriate social-distancing precautions, Salmon anticipates “a quiet opening” for the show — not least because Scott won’t be making the long trek at that time of year from snowbound Wyoming. The artist does, however, plan to visit sometime later in the spring, when a more formal celebration will be held. Whenever that happens, one could say that it will be a show long in the making — though the precise length of time depends on whether you measure it by Scott’s four-decades-long passion for Brookgreen, her 50-plus years as a professional artist, the nine-decades-long history of Brookgreen Gardens, or the two centuries of nature-based art on display.

No Comments