19 Jan Balance in Tension

A PICTURE, AS THEY SAY, IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS, but Colorado artist Jill Soukup has a way with words as well as with paint. Whether you’re looking at her work or listening to her talk, you quickly understand that she spends as much time thinking about her methods and subjects as she does actually moving paint around with brushes.

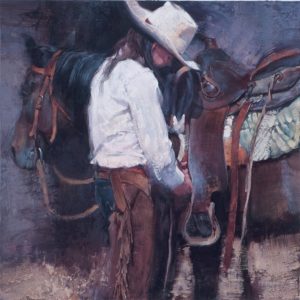

“Saddling Up” | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 30 inches | 2014

“If you talk to my students,” she explains, “they’ll tell you that ‘intention’ is a big word for me, that I emphasize it as an important part of the creative process.” She brings plan and purpose to every element in her paintings, from the general features of a composition down to the individual brushstrokes in its execution. Like many children growing up in the West, she says she was obsessed with horses. But as the child of a veterinarian, she came to appreciate them in perhaps more technical ways than most kids, down to the arrangement of muscle and sinew beneath the skin. “My father had these veterinary models that I would study and play with,” she says.

Accordingly, her sense of intention as she works goes far beneath the surface of the subjects or the paintings of them. She describes how, in Chico Basin Percherons, for example, “[her] intention was to keep the sky and mountains in the same value-family in order to bring more attention to the horses.” It’s a stunning effect: The background in which the horses are enveloped is moody and evocative, but the soft focus on the scenery and the way she handles light in the painting gives the horses a kind of sculptural quality; it really is as if these percherons are present in more than two dimensions.

“Chico Basin Percherons” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 72 inches | 2015

“Chico Basin Percherons” | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 72 inches | 2015

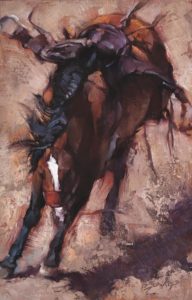

Sometimes, no matter how contemporary an artwork may seem, our search for words with which to talk about it sends us back to the ancient Greeks. So it is with Soukup, whose work is driven by a profound understanding of balance through tension. One painting captures a stunning display of equine mood and movement, for example, while another documents the stately, placid presence of an industrial railroad car. It so happens that the Greeks had a word — enantiodromia — to describe a sort of balance achieved through the study of things that appear opposed, a kind of yin-yang notion in which the integrity of the whole is derived from an internal tension driven by mirror opposites.

“Catching Cattle” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 24 inches | 2017

Soukup’s work is a visual exposition of the principle. In her artist’s statement, she writes, “[t]he intent of my work is to capture the balance that exists at the intersection of opposite elements and to expose underlying similarities in things that are perceived to be fundamentally different.” She elaborates further, explaining that it’s “the symbiotic duality that defines my work — each element is dependent on its opposite for complete expression.”

Her instinct for the power of enantiodromia emerges in her work at every level, from the way she uses color to her choice of subjects. She’s as adept at capturing the beauty of an industrial setting as she is a horse gamboling in a meadow. She talks naturally about what she calls the “organic quality of architectural images” and speculates that what she calls her “mechanical obsession” began in a photography class in college. “I remember photographing an abandoned building, a factory of some kind, and being struck by the tension between the vast, blank space and color value of a huge factory wall, and at the same time by the intricate web and network of pipes and wheels everywhere,” she says.

“Saddle Splay” | Oil on Canvas | 11.5 x 7.5 inches | 2017

Seeing the organic in the architectural is one thing, but the converse also comes naturally to her: the ability to discern in the organic image — a horse in motion, say — a kind of mechanical beauty of motive force embodied in fleshly machinery. “Lately I’ve been painting a sorrel horse on a ranch where I do a lot of my work,” she explains, “and I have become really interested in the way the sunlight reflects off this animal. It’s as if his coat is copper, metallic.”

After you’ve heard her talk in such clear visual terms about both horses and railroad cars, and you compare her work in what appears to be two disparate realms, you can see what she means: the folded tension in a coyote’s legs painted in mid-gallop, for instance, does seem to echo the structure of the wheel carriage under a tanker car. And probably only a mechanically minded artist would choose to immortalize, alla prima, a giant bison scratching itself with its rear hoof in an ungainly but wholly natural pose, as in Bull Scratch.

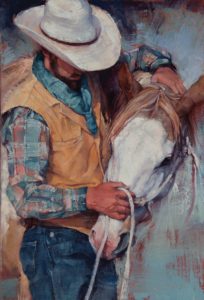

In the first of two major shows coming up in 2018, Soukup will be featured as one of 58 artists selected for Cowgirl Up! Art from the Other Half of the West Exhibition & Sale, March 25 through May 13, 2018, at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg, Arizona. Soukup’s Tough & Tender earned Best in Show at last year’s event.

“Tough & Tender” | Oil on Canvas | 20 x 14 inches | 2016

Now in its 13th year, the Cowgirl Up! event originated as a response to the “males only” exclusivity of the Cowboy Artists of America. “We responded 13 years ago with an all-women show, which was a tremendous success,” explains Amanda Schlueter, Desert Caballeros Museum curator. “One special element that adds to Cowgirl Up! is that we kick it off with a three-day celebration — we block off the street and have a big party that opening week.”

In her second major show of the year, Soukup will be one of a trio of artists featured in a show titled The Art of Ranching & Conservation at The Sangre de Cristo Arts Center in Pueblo, Colorado. Taking place October 13, 2018, through January 13, 2019, Soukup joins artists Duke Beardsley and Terry Gardner in a show she describes as “a collaboration between artists and ranchers designed to foster conversation about art, conservation and the ranching way of life.”

That show will feature her paintings from the Zapata Ranch, which espouses an environmentally conscious ethic aimed at returning the landscape to pre-European practices, including the reintroduction of bison on its more than 100,000 acres. She spends considerable time at the ranch in the San Luis Valley in Colorado, which adjoins the Great Sand Dunes National Park.

“Bull Scratch” | Oil on Canvas | 9 x 9 inches | 2014

“Bull Scratch” | Oil on Canvas | 9 x 9 inches | 2014

“The ranch is owned by the Nature Conservancy,” she says, “and they partner with Ranchlands, where part of their mission is to develop new ways to look at ranching.” Bull Scratch, in fact, is a product of her time at Zapata.

“Turquoise & Copper” | Oil on Canvas | 31 x 16 inches | 2017

“Jill Soukup has quickly moved beyond ‘emerging artist’ status, in my view,” says Greg Fulton, owner of Astoria Fine Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, which will host a two-person show featuring Soukup and artist Eric Bowman in August 2018. “We have a lot of professionals — well-established artists — who pretty much on a daily basis come in and ask to see her work, to examine the technique and her brushwork.”

Fulton first saw her work in a show in Denver, Colorado, and was mesmerized by the power and mastery of her paintings. “I mean, her work just stood out: the big brush strokes, the impressionistic use of a lot of paint and the color. She has an amazing palette.”

“Yellow Headed Blackbird” | Oil on Canvas | 12 x 12 inches | 2017

It is always impressive when an artist’s control over their work is matched by their talent for talking intelligently about it. It’s not easy to find an effect in Soukup’s work that she can’t explain, because she knows what she’s doing and why she’s doing it. Still, from the time of the Greeks, we’ve known that the best art travels beyond words to connect to the world we inhabit with our eyes.

No Comments