17 Jan Perspective: Eduardo Carrillo [1937–1997]

At just about the time that Eduardo Carrillo [1937–1997] was up for tenure in his teaching position at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) in the 1970s, he became aware that an African-American member of his department was being left out of some activities. So he wrote a letter to university officials, objecting to the woman’s treatment. When the tenure committee read the letter, they asked him to rescind it, implying that not doing so could hinder his chances of receiving tenure. He refused.

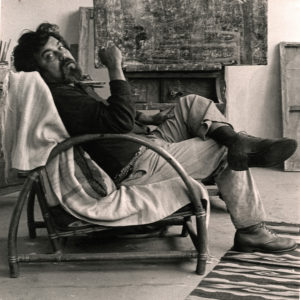

Eduardo Carrillo at his studio in Ben Lomond, California, in the early 1980s. Photo by Cruz Ortiz Zamarrón

“He stood up for his values. He was an advocate for the disenfranchised,” says Susan Leask, guest curator of Testament of the Spirit: Paintings by Eduardo Carrillo at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, which runs through June 3, 2018. The exhibit was organized by the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, and will be on view there June 24 through October 7, 2018. It then travels to the Triton Museum of Art in Santa Cruz, the American University Museum in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere.

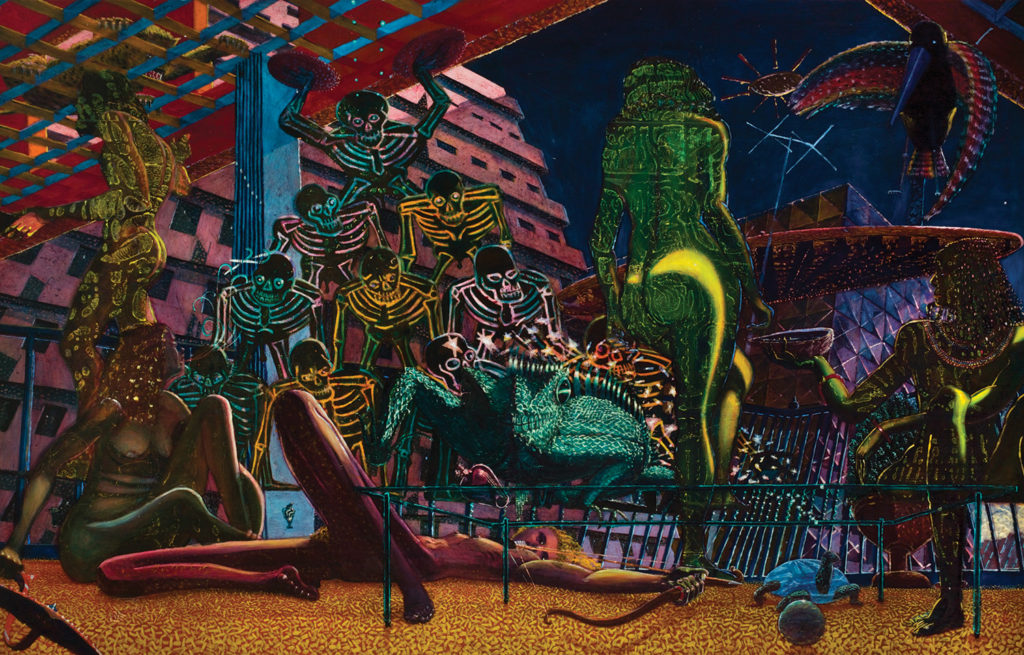

The exhibition’s 60-some paintings reflect the mediums and formats Carrillo employed — small watercolors, large-scale oils and murals. Many of his large pieces feature complex compositions vibrant with color and filled with archetypal figures and suggestions of magical realism, mythology and indigenous spirituality, often within fantastical landscapes. His more simple and intimate watercolors focus primarily on quiet elements of domestic life.

Carrillo — who did gain tenure and taught at UCSC until his death in 1997 — was known for promoting greater understanding and appreciation of Chicano/Latino culture, history and identity through his art, teaching and life. Yet his sense of inclusiveness extended to everyone, says Betsy Andersen, an artist, curator and former student of Carrillo’s at UCSC. Andersen is founding director of Museo Eduardo Carrillo, an online museum and the only artist-endowed foundation dedicated to a Mexican-American artist in the U.S. “There was a quality of acceptance that people felt by coming into contact with Eduardo,” she says. “It was as if when you came in the door as who you were, it was the most perfect thing you could do.”

“The Aerialist” | Oil on Canvas | 76 x 51 inches | 1994 | Private collection

Nourished by deep family roots in Baja California Sur, Mexico, where his mother was born and his grandmother lived, Carrillo was born in Santa Monica, California, and raised, the youngest of five children, in South Los Angeles. His highly creative father was a commercial artist and chief designer at the Los Angeles Souvenir Company. Carrillo’s brother, Alex, is an artist who has taught drawing and painting for many years. Carrillo grew up inspired by his father and brother, although as a boy he didn’t consider himself unusually talented. Alison Keeler Carrillo, the artist’s widow, recalls her husband describing himself as the “fifth-best drawer in grade school.” But he also remembered being captivated as a child by the religious paintings, stained glass and statuary in churches, both in L.A. and in his grandmother’s village of San Ignacio in Baja California Sur.

By the time he was a sophomore at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Carrillo was beginning to immerse himself in art. “I really felt at home there for the first time, because people were interested in what I was doing, and I was interested in what they were doing,” he says in an interview in “Eduardo Carrillo: A Life of Engagement,” a film by Pedro Pablo Celedón, produced by Museo Eduardo Carrillo.

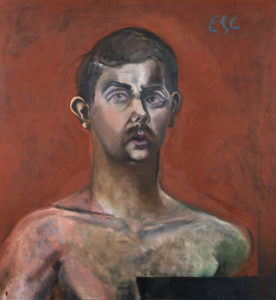

“Self-Portrait” | Oil on Canvas | 29.5 x 27.75 inches | 1960 | Private collection

As a young art student in 1960, Carrillo followed his passion for European painting to Spain, having worked in a L.A. machine shop to earn money for the trip. Especially drawn to Hieronymus Bosch, El Greco and Diego Velázquez, he spent a year in Madrid, studying and copying paintings at the Museo del Prado. There he explored methods and materials of the Old Masters and taught himself the glazing technique he used from then on. After returning to Southern California, he completed his bachelor of fine arts and earned a master of fine arts, both from UCLA.

In 1966, Carrillo and his first wife, Sheila, spent three years in La Paz, Mexico, where his father had been born. Working with a local potter of Zapotec heritage, the couple established El Centro Regional de Arte, aimed at employing young people in teaching pottery while promoting and preserving the region’s traditional crafts. While in La Paz, Carrillo began delving into indigenous and Mexican cultures, deepening and expanding his knowledge and appreciation of his own spiritual, historical and cultural roots. This personal exploration coincided with the rise of the Chicano movement in the U.S., with its struggle for civil and political rights and the emerging issues of ethnic identity and cultural pride.

“Las Tropicanas” | Oil on Panel | 84 x 132 inches | 1972–1973 | Crocker Art Museum | Promised Gift of Juliette Carrillo and Ruben Carrillo

“Las Tropicanas” | Oil on Panel | 84 x 132 inches | 1972–1973 | Crocker Art Museum | Promised Gift of Juliette Carrillo and Ruben Carrillo

Back in California by 1969, Carrillo took part in street demonstrations to some extent, but his greater contribution to Chicano/Latino activism was through his art. “He was definitely a champion of whatever-it-takes, and he didn’t believe that those who were more strident were not right. But he felt they could do that better than he could. His was more of a gentle activism,” Leask says.

“Birth, Death, and Regeneration,” 1976. Palomar Arcade (mural destroyed), Santa Cruz, California. Politec on masonry, over 2,500 square feet. Photo by Cruz Ortiz Zamarrón

In Sacramento, where he accepted a teaching position at California State University in 1970, Carrillo was part of a wide-ranging and influential artist collective called the Royal Chicano Air Force. He also worked with three other painters — Saul Solache, Sergio Hernández and Ramses Noriega — to create the nine-panel mural, Chicano History (1970), for the Chicano Studies Center at UCLA. Carrillo’s portion of the mural reflects his time in the Mexican desert and his growing understanding of indigenous spirituality, especially the “union of the Indio with the spirit of nature,” as he describes in the film.

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican spirituality, along with imagery suggestive of Christianity and Carrillo’s personal mysticism also came together in the 1976 mural, Birth, Death, and Regeneration. The mural completely covered the walls and curved ceiling of a narrow hallway entrance into the Palomar Arcade mall in Santa Cruz.

“It really embodied his life and philosophic and cultural beliefs,” says Andersen, who, as a student, helped work on the project. Carrillo envisioned the mural, whose enormous, powerful figures virtually embraced those who walked through the entranceway, as creating a “sacred space of pure love to serve humanity,” Leask says. Unfortunately, the Palomar Arcade’s owners saw it more as a potential loitering spot for vagrants. Without asking or informing the artist, they had the mural painted over in 1979. “I think it broke Ed’s heart,” his wife, Alison, recalls.

Eduardo Carrillo and assistant Betsy Andersen working on “Birth, Death, and Regeneration.” Photo: Edward Ramos

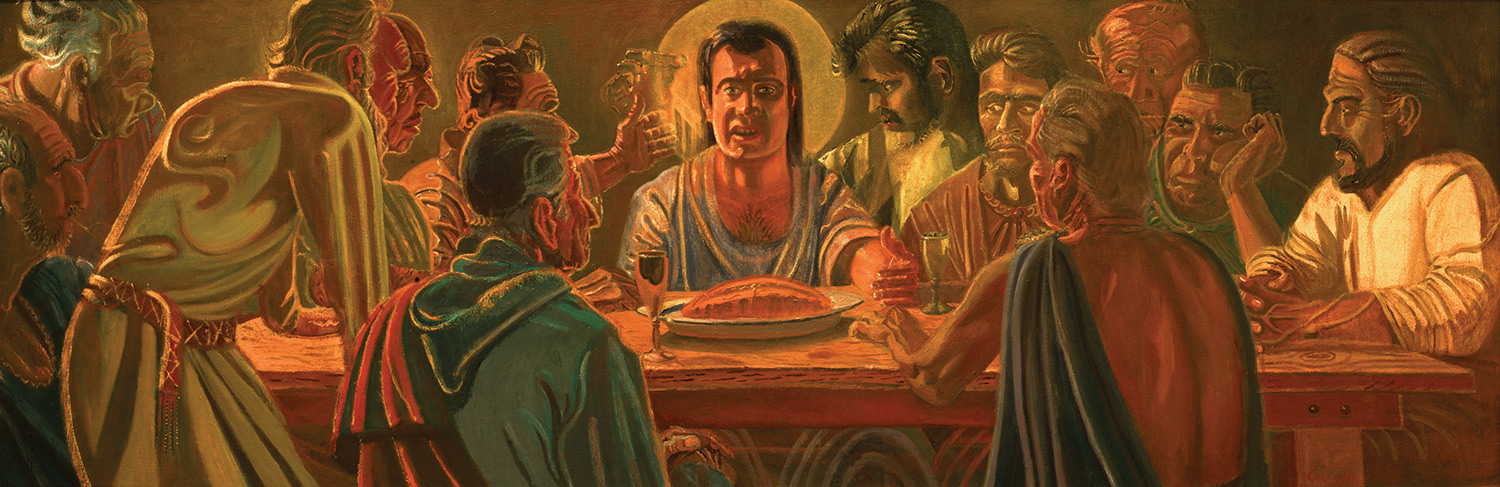

Every year for most of his adult life, Carrillo spent time at the property that had been his grandmother’s home in San Ignacio, where he incorporated the rich oasis vegetation, transcendent light and local people into his art. For La Última Cena (The Last Supper), he enlisted friends and neighbors from the village to pose as Christ and the apostles.

Leask points to the same suggestion of layered meaning and depth in the artist’s watercolor depictions of everyday objects. In the habit of getting up early and sitting at the kitchen table to create small watercolor still lifes, he often painted whatever happened to be around — like the reading glasses he’d taken off the night before. Ed’s Glasses is a light-infused image that speaks of “physical and emotional ease at the end of a long day of teaching, a time of repose,” Leask says. She and others describe the artist’s personal side as defined by warmth, humor and imagination — a life filled with mirth and surprise.

Carrillo’s paintings have been exhibited in dozens of solo and group shows around the U.S. and Latin America and are in the permanent collections of several museums. Yet those whose lives he touched say his legacy lies at least as much in his heartfelt, tireless encouragement of his students and promotion of fellow artists.

“Ed’s Glasses” | Watercolor on Paper | 7.125 x 10.125 inches | Private collection

“Everyone who came away from working with him felt they had a powerful story of their own to tell,” Andersen says. “I think Eduardo wanted everyone to find their personal voice.”

At California State University, Monterey Bay, Leask continues to use Carrillo’s art and regional art history as a vehicle for helping unfold her students’ creative expression. One student, barely a child when Carrillo died, became enthralled with a figurative painting left unfinished in the artist’s studio. Seeing the underpainting and imagining where Carrillo might have gone with the piece, the student took photos of the painting, reproduced it and finished it. Working on it, he felt as if he shared in the artist’s sensibility and consciousness, Leask says. “This student was so passionate. I see Carrillo’s work not just as art in museums. He’s still touching people in ways that we need to be touched.”

Eduardo Carrillo, Sergio Hernández, Ramses Noriega and Saul Solache “Chicano History” | Oil on Panel | 144 x 264 inches | 1970 | Chicano Studies Research Center, University of California, Los Angeles | Image courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

Eduardo Carrillo, Sergio Hernández, Ramses Noriega and Saul Solache “Chicano History” | Oil on Panel | 144 x 264 inches | 1970 | Chicano Studies Research Center, University of California, Los Angeles | Image courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center

No Comments