19 Jan In the Studio: Joyful Collaboration

Ever since meeting in the fiber arts department at the Kansas City Art Institute 44 years ago, Mary Dee and Allen Dodge have been joyful collaborators. Together, they’ve raised a family, run a business and developed complementary art careers.

Eclectic and filled with pattern, the living/dining room offers a floor-to-ceiling view of their secluded yard well above the lake.

Eclectic and filled with pattern, the living/dining room offers a floor-to-ceiling view of their secluded yard well above the lake.

Intrigued by the Northwest during a cross-country trip, the Dodges relocated to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in time to snag commissions for Spokane, Washington’s Expo ’74, creating several commissions for the country’s first environmentally themed world’s fair. They progressed to historical restoration work, led workshops and exhibited their artwork. Allen worked as a cartoonist and Mary Dee as a studio potter.

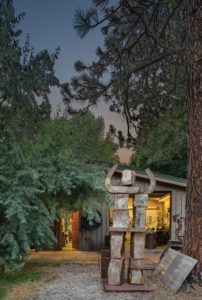

Allen’s Shop Guardian stands tall outside his studio.

In 1985, they began a screenprinting business that included nationally marketed, custom-painted dresses and shirts as well as political signs for their friend and six-term Idaho senator, Mary Lou Reed. It was while visiting Reed and her late husband, Scott, that the Dodges discovered the hillside property where they now live.

As much as they’ve collaborated, however, the Dodges have distinctly different styles and ways of working.

“He’s the cartoonist,” says Mary Dee.

“She loves pattern and color,” says Allen, from the kitchen of their 1955 home located on the periphery of Coeur d’Alene National Forest, which spans the Idaho-Montana border. With its open-frame fireplace, abundant windows and colorful décor, the kitchen, says Allen, is his wife’s other studio. He’ll often draw or do the finish work on enamel jewelry that Mary Dee has created, while she cooks elaborate, geographically diverse meals.

“I always say that I never have to finish anything,” jokes Mary Dee, whose intricately painted ceramics line the upper shelf of kitchen cupboards amongst Majolica pottery from the couple’s travels.

Mary Dee at work in her studio.

Mary Dee at work in her studio.

Their home — inside and out — is a testament to travel, family and friendships with artists, including Harold Balazs, a jack-of-all-trades who creates everything from large, abstract metal sculptures to murals, jewelry, furniture, drawings, stained glass and wooden boats, and is also known for his outsider-art style and mastery of enamel.

Detail of a recent commission.

Allen studied enameling with Balazs in 2007. “The depth of [Harold’s] knowledge and curiosity was mind-boggling,” says Allen, whose monochrome enamels use Balazs’ technique of layering white and black to resemble a drawing or print.

Mary Dee was also influenced by Balazs and has modified some of the artist’s techniques. Working in the studio, she sifts colored-glass powder over shapes of metal, no greater than 9 inches, that she cuts with a band saw. These lustrous, vibrant shapes are then fired in her tabletop kiln. “It forces me to piece things together,” says Mary Dee. Some enameled pieces are layered in bas-relief to create individual works, while others are assembled onto Allen’s sculptures. Capriole, for instance, adds selective color enamel to Allen’s typically rust-patinated surfaces.

Mary Dee’s 16-by-24-foot studio is neat and bright with little on the walls or worktables other than whatever she’s currently working on. She moves around a central table, examining pieces from various angles as music — jazz, classical guitar, opera — plays in the background. A bookshelf reveals varied influences: Wassily Kandinsky, Navajo rugs, African designs, figurative drawing, Georgia O’Keeffe, painting on fabric. Jars of Thompson enamel powder are organized in drawers under a wraparound worktable, culminating in a small painting and sketching area. A massive window reveals a view of their house and one of Allen’s sculptures, Owl, at the edge of the couple’s 1.3-acre property.

Mary Dee can see Allen’s owl sculpture from her studio window.

Mary Dee can see Allen’s owl sculpture from her studio window.

Across the property is Allen’s work area, a converted 24-by-32-foot garage surrounded by vestiges of past and new artworks. There is a tang of metal in the air left over from when he used the grinder to create a tumbled-stone look on a large-scale welded steel sculpture, such as Sanctuary and Gather.

Allen in his shop.

Abstract forms are methodically laid out on the largest shop wall. Industrial casting molds from an 1800s lake cruise company were given to the couple by Balazs and the late Patrick Flammia, a longtime friend and accomplished local artist. Otherwise, the shop is a jumble of tools for welding, woodworking, enameling, printmaking and sketching.

“You just want to be able to turn around and do it and not make a big deal out of getting the job done,” says Allen, who smiles when saying he is not a purist.

He even builds his own tools, including the cobbled-together kiln for firing larger works, made from parts Balazs gave him. Although the Dodges have discussed moving the kiln into Mary Dee’s studio and perhaps getting a larger kiln, it gives Mary Dee a reason to visit.

He uses every inch of his 24-by-32-foot shop to create large-scale commissions, like this one in progress.

He uses every inch of his 24-by-32-foot shop to create large-scale commissions, like this one in progress.

And, of course, there’s always the kitchen, where they’ll convene nearly every evening, sharing a glass of wine and a meal, along with news of the day’s events and plans for the future.

“The Protector” welcomes visitors to the couple’s Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, home.

“Mary Dee and Allen live their lives as a dance,” says Barb Pleason Mueller, an artist and friend, who, with her husband Marty, runs a nonprofit maker-space in the Dodges’ former printshop. “Even in their own uniquely separate spaces they are aware and connected to each other’s movement and thoughts,” she says. “That creative energy binds together their different methods into creating their next inspired piece of art.”

No Comments