09 May Perspective: Albert Bierstadt [1830–1902]

Albert Bierstadt’s last great painting was a grand-manner allegorical canvas recounting the impending demise of the two prime symbols of the American West, the buffalo and the Plains American Indian tribes. It is titled The Last of the Buffalo (1889). So important was the subject that he produced two epic-size versions, one today in the National Gallery of Art and the other in the collections of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Together, they are regarded as his finest late works.

Bierstadt has been known as one of America’s most renowned landscape painters of the West, so it seems anomalous that he would culminate his career with a pair of figural works that featured a dramatic collision of buffalo and American Indians. Yet the artist, from the beginnings of his exposure to the West, felt as much passion for the Native peoples of the plains and the fauna of the region as for the grand landscapes of the Rocky Mountains and the Sierras. His surviving sketchbook from his first western trip in 1859 is filled with drawings of animals, especially bison, and his photographs and earliest oil studies portray the Sioux and Shoshone of present-day Nebraska and Wyoming.

“The Last of the Buffalo” | Oil on Canvas | 60.25 x 96.5 inches | Circa 1888 | Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming | Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Trust Fund Purchase, 2.60

“The Last of the Buffalo” | Oil on Canvas | 60.25 x 96.5 inches | Circa 1888 | Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming | Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Trust Fund Purchase, 2.60

Once he returned east from his initial travels, Bierstadt produced a number of important paintings of American Indian encampments and themes from everyday life, such as Indians Near Fort Laramie (1861) and View of Chimney Rock, Ogalilah Sioux Village in the Foreground (1860). His first large, highly acclaimed canvas, titled Base of the Rocky Mountains, Laramie Peak (1860, now lost), combined a spectacular mountain vista with a Sioux buffalo hunt in the foreground.

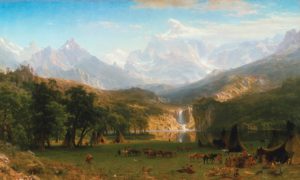

Following that initial effort at producing an epic-sized Western landscape enhanced with a sensational scene of American Indians and bison, Bierstadt turned to the production of two monumental canvases picturing Shoshone encamped at the base of Lander’s Peak (today’s Temple Peak) high in the southern reaches of Wyoming’s Wind River Range. One of these grand vistas, The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak (1863), was one of a triumvirate of such early masterpieces. Some critics praised the work for successfully combining American Indian subjects with mountain vistas but most did not. In fact, the majority claimed that such a union severely compromised the work’s integrity, saying that the artist had “sacrificed sublimity for variety,” a combination that was defined as “a serious aesthetic fault.”

“The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak” | Oil on Canvas | 73.5 x 120.75 inches | 1863 | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York | Rogers Fund, 1977. 07.123

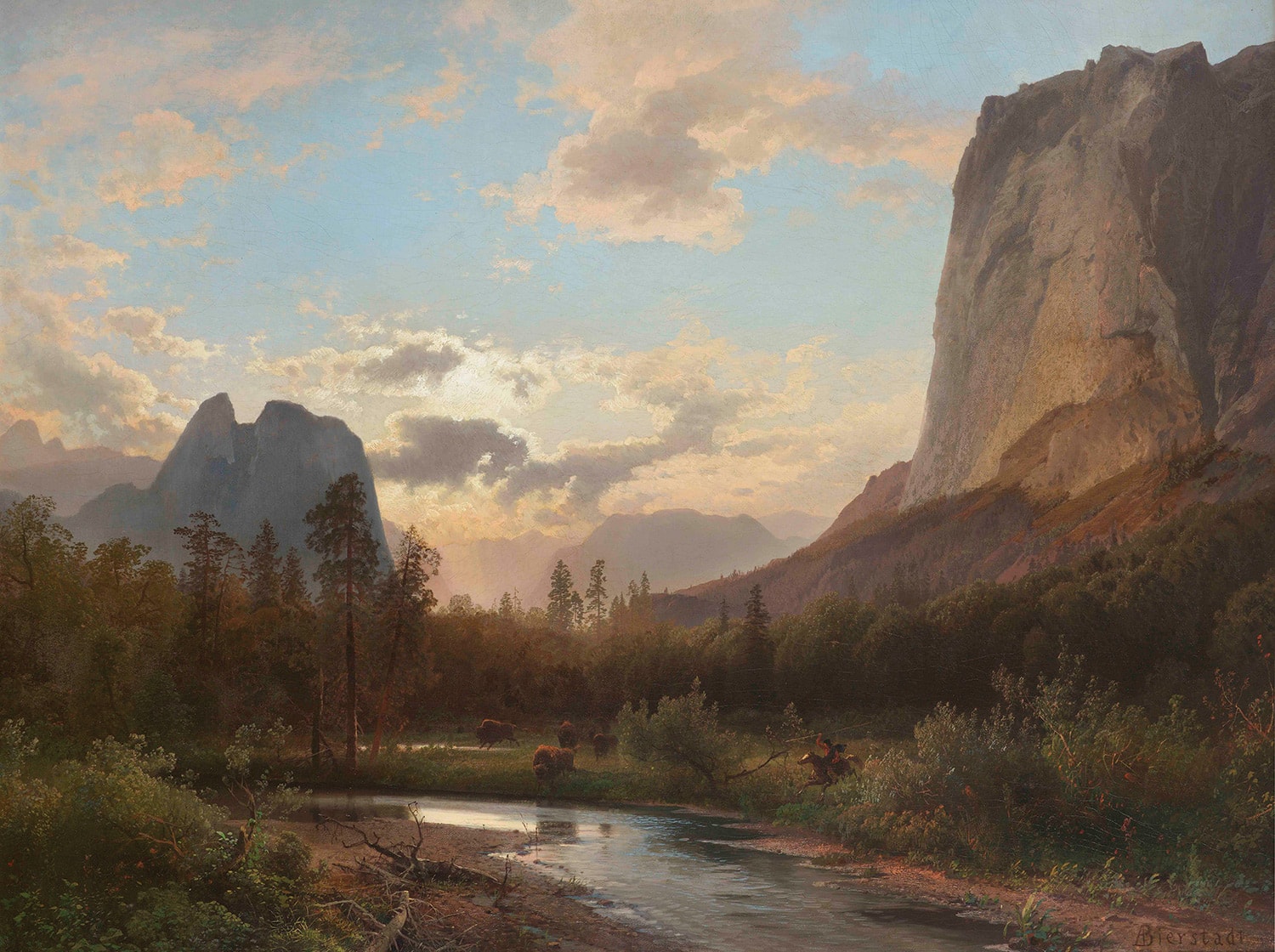

“The Buffalo Trail” | Oil on Canvas | 31.875 x 48 inches | 1867 | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865. 47.1268

Bierstadt, then, had to decide which direction he would take his career, and he chose to become essentially a landscape painter. American Indians as subjects, to his lament, would have to be abandoned or at least marginalized. With the rare exception of Buffalo Hunt, Bierstadt paintings after 1863 generally avoided recording the Native American presence in the West.

In 1863, Bierstadt took a second trip west. In the company of his friend, travel writer Fitz Hugh Ludlow, he rode a stagecoach through Nebraska Territory to Denver, Colorado, and ultimately to California. Between the Missouri River and Denver, Bierstadt encountered a few extremely large herds of buffalo and, with his colleagues, participated in a buffalo hunt. While he was an inveterate sportsman, Bierstadt often did not shoot on occasions such as this, allowing himself instead to record the chase and study the bison’s form. Several important works on the buffalo theme resulted from that and subsequent similar experiences, such as his bucolic Buffalo on the Plains (c. 1863).

As Bierstadt retreated gradually from portraying American Indians in his work, one related subject seemed to pass muster with the critics, and that was the buffalo. Such paintings tended to be prairie scenes, and through the decades of his early success, in the 1860s and 1870s, Bierstadt explored numerous opportunities to combine the buffalo with the Western landscape.

“Buffalo Trail: The Impending Storm” | Oil on Canvas | 29.5 x 49.5 inches | 1869 | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Corcoran Collection | Museum purchase, through the gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lansdell K. Christie. 2014.79.3

“Buffalo Trail: The Impending Storm” | Oil on Canvas | 29.5 x 49.5 inches | 1869 | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Corcoran Collection | Museum purchase, through the gift of Mr. and Mrs. Lansdell K. Christie. 2014.79.3

In the late 1860s, as the transcontinental railroad began to cut its way across the plains, Bierstadt produced two major bison paintings, The Buffalo Trail and Buffalo Trail: The Impending Storm. The former work is a pastoral celebration of an unspoiled, gloriously wooded river bottom (probably the Platte) with intimations of abundance, regeneration and nature’s unspoiled wonder. The latter, finished the year the tracks were completed, recounted a fundamentally different narrative. Here, clouds of uncertainty loom above the herd and a melancholic tone prevails, suggesting the buffalo’s doom is near. Bierstadt had read the situation correctly as voracious hide hunters were invading the plains in increasingly large numbers and would, within the next decade, virtually exterminate the bison while also devastating the livelihood of the American Indians that Bierstadt was prohibited by aesthetic tastes from depicting.

In 1875, Bierstadt painted a resplendent buffalo scene that was exhibited in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition the next year. Titled Western Kansas, it presented an elegiac display of buffalo moving quietly along the banks of a prairie stream. It suggests loss and remembrance, appropriate sentiments for a moment in history when mass butchery was being perpetrated on the remnant herds of the West. It was a sad commentary on the nation’s state of affairs at her 100th birthday. The American Indians, too, were being subdued, rounded up and pushed onto reservations, but Bierstadt chose to only include them by inference.

By the late 1880s, the bison were all but gone from the prairies. A handful of voices rose to proclaim the tragedy and strove to save the few that remained in the confines of Yellowstone National Park. Ironically, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, in 1883, was among those to call for last-minute conservation efforts that centered on stopping the rampant poaching of the park’s animals. But the real push came from a noted journalist, George Bird Grinnell (editor of Forest and Stream magazine) and Theodore Roosevelt who formed the world’s first wildlife conservation organization officially in 1888, the Boone & Crockett Club.

“Indians Traveling Near Fort Laramie | Oil on Canvas | 23 x 41 inches | 1861 | American Western Art Museum — The Anschutz Collection, Denver, Colorado

“Indians Traveling Near Fort Laramie | Oil on Canvas | 23 x 41 inches | 1861 | American Western Art Museum — The Anschutz Collection, Denver, Colorado

Bierstadt was a charter member of that club, and its first formal matter of business was to bring sufficient governance to the park to preserve its treasures, including the 300 buffalo that remained in that vulnerable sanctuary. By that date, American Indians had been banished from the park despite the fact that the Crow, by treaty, had owned the land on which the park was situated. Bierstadt saw a chance to contribute to the cause as only an established, grand-manner painter could, by producing a pair of monumental pictorial chronicles lamenting the demise of the bison and the vastly diminished presence of the Plains tribes.

It is the perspective of the upcoming June exhibition, Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, in partnership with the Gilcrease Museum, that the two versions of The Last of the Buffalo were Yellowstone narratives (Bierstadt had visited the park for several months in 1881). They were painted to help bring national and international attention to the preservation efforts in the park.

Both versions were ultimately sent to Europe. The National Gallery’s version traveled to the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, however, circumstances prevented the painting’s display at that event. Bierstadt was able to show it in the Paris Salon and subsequently at a commercial venue, the Boussod-Valadon Gallery. The Buffalo Bill Center’s version went to London in 1891 where, during a display at the Hanover Gallery, it was purchased by Colonel John Thomas North for his lavish estate in Eltham. It brought a price of $50,000, the highest amount ever paid for an American painting in the 19th century.

“View of Chimney Rock, Ogalilah Sioux Village in the Foreground” | Oil on Board | 13.25 x 19.375 inches | 1860 | Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine | Gift of the Honorable Roderic H.D. Henderson. 1964.026

“View of Chimney Rock, Ogalilah Sioux Village in the Foreground” | Oil on Board | 13.25 x 19.375 inches | 1860 | Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine | Gift of the Honorable Roderic H.D. Henderson. 1964.026

While the National Gallery’s version was in Paris, so was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West exposition. Bierstadt, Buffalo Bill and the French animalier painter Rosa Bonheur formed close friendships. In fact, Bierstadt had sketched the exposition in the summer of 1888 while the showman was camped on Staten Island. The painting, The Last of the Buffalo was painted there, confirming the artist’s sustained devotion to the idea of the American Indian and bison as fused icons of the West. One of the exposition’s most famous American Indian performers in Paris, the Oglala Chief Rocky Bear, became enamored of The Last of the Buffalo, displayed in the window of the Boussod-Valadon Gallery. He brought his fellow Sioux performers to view the painting as well. Collectively, they stirred such excitement in central Paris that they attracted the attention of a reporter from The New York Times.

Rocky Bear waxed eloquently, saying the painting offered “breath and life to the glorious past of” his people and the buffalo. According to the reporter, Rocky Bear’s reaction was a powerful “recognition of the truth of the scene and … an eloquent [testimony] to its sentiment and poetry.” Thus, through art, the legacy of the Native Plains people was reunited with the buffalo in Albert Bierstadt’s last great painting, a grand-manner triumph.

Sadly, despite the Boone and Crockett Club’s vigorous efforts, the nation’s bison population continued to decline over the next several years. But in 1894, Congress passed the Lacey Act (named after its author, Congressman John F. Lacey), which protected the bison from the ravages of poachers. Historian Michael Punke has written that the “story of how the buffalo was saved is one of the great dramas of the Old West,” and that with the passage of the Lacey Act, the national park idea transformed from a concept into a commitment.

Bierstadt had, throughout his career, worked to show that the story of the buffalo and the American Indian was a supreme national epic. A substantial part of the artist’s legacy should then include recognition of Bierstadt as a principal chronicler of that poignant and tragic saga.

Editor’s Note: Albert Bierstadt: Witness to a Changing West opens June 8 and runs through September 30 at Cody, Wyoming’s Buffalo Bill Center of the West. It then travels to Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Gilcrease Museum, November 1 through February 10, 2019.

No Comments