10 May Exalting the Everyday

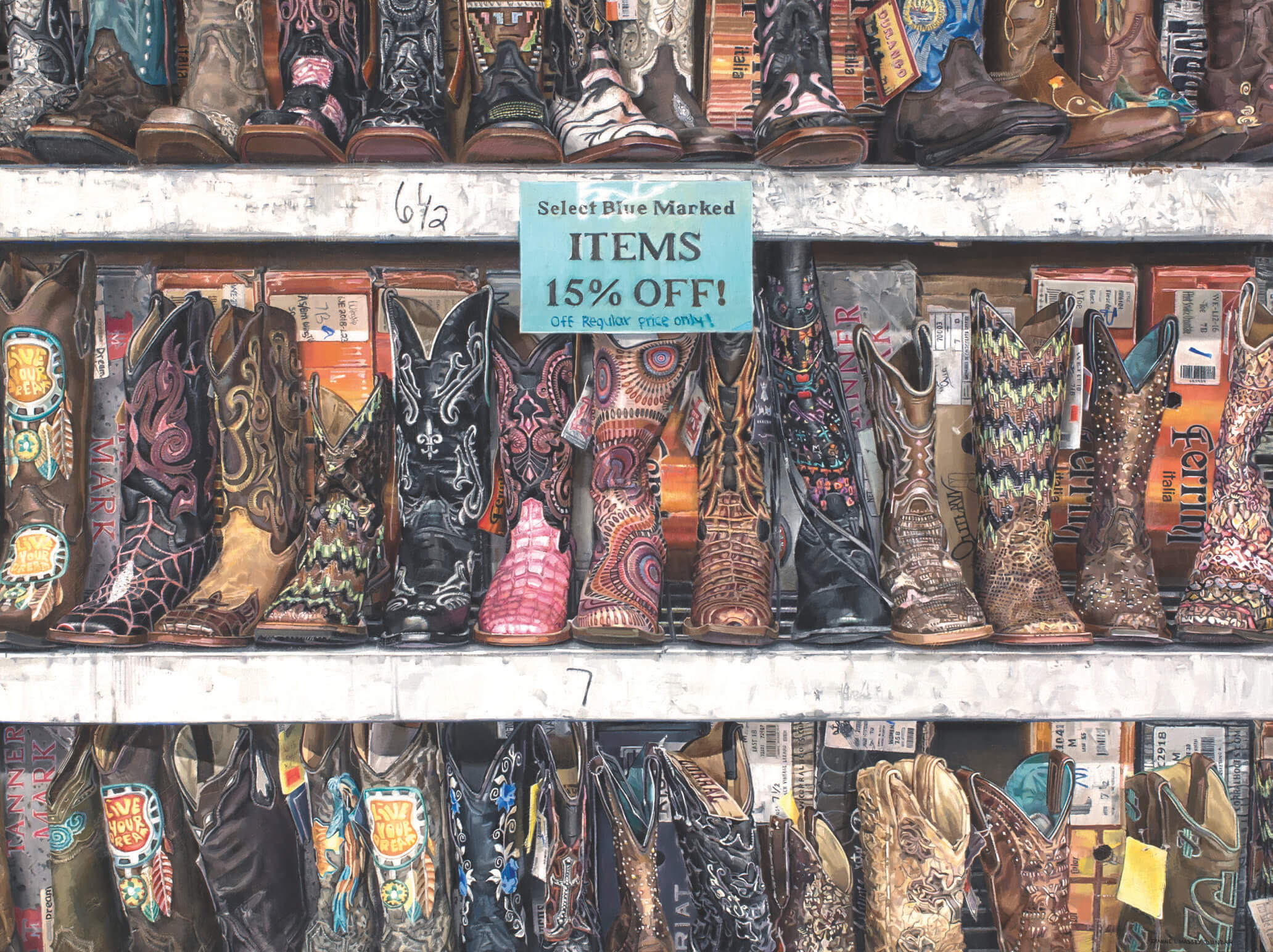

In mid-January 2020, while walking through the merchandise area of Denver’s National Western Stock Show on her way to seeing her paintings displayed for the first time in the prestigious Coors Western Art Show & Sale, a display rack stopped Dianne Massey Dunbar in her tracks. “They had all these cowboy boots for sale, and I was mesmerized by the textures and the embroidery and the smell of the leather,” she recalls, her voice still tinged with wonder. “So, I did a whole photoshoot, exploring the boots.” She snapped more than 50 images, making sure to capture such mundane details as a bright blue “15% OFF!” sign and random tags and bar codes, not to mention the worn paint on dinged shelves with sizes scrawled in felt-tip pen.

A Little Bit of Happy | Oil on Board | 24 x 24 inches | 2022

At that debut Coors outing, Dunbar’s selection of exquisitely detailed paintings of the “ordinary scenes and ordinary objects” she loves to portray — a range of works typified by neon-lit roadside diners viewed through rain-blurred car windshields, witty still-lifes of pantry items and children’s toys, or intricate close-up traceries of plant life — were enthusiastically received. She has been juried into the show every year since, and in 2021 her body of work there was chosen to receive the Western Art & Architecture Award of Excellence, the latest in an impressive array of honors earned in exhibitions from prestigious organizations that also include Oil Painters of America and American Women Artists.

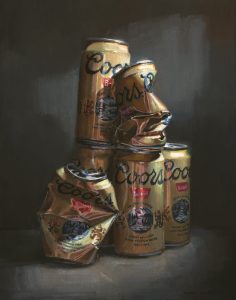

Friday Night During the Pandemic | Oil on Board | 14 x 11 inches | 2021

Meanwhile, those boots photos, stored away on her Mac, continued to beckon Dunbar’s imagination, demanding to be painted. Finally, this past year, she decided to heed their call, intending the painting to be her showstopper for the 2023 Coors event. While she was painting it, however, the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, caught wind of the work and eventually offered to buy it even before she had finished it last fall. This past February, the 30-by-40–inch oil-on-board painting, entitled These Boots…, went on permanent, prominent display as the introductory image for the museum’s exhibition space, featuring a collection of practical yet decoratively made Western items such as firearms, holsters, chaps, saddles, belts, and — yes — boots. “That’s my first museum piece,” Dunbar says. “I feel very privileged and honored.”

The painting marks a major milestone for Dunbar in a professional art career now spanning 23 years, fueled by a love of painting that stretches back more than six decades.

Covenant | Oil on Board | 18 x 36 inches | 2021

The second-generation Coloradan’s talent revealed itself at the age of 7 when her elementary school teacher “approached my parents and told them she was of the impression that I showed an aptitude for art.” Young Dianne’s mom and dad took action, signing her up for weekly Saturday afternoon small-group lessons taught by noted Denver artist and illustrator Harold Wolfinbarger Jr. “They were all adults in the class, and I was the only child he ever took on,” she says. At first, she was confined to a separate room and only allowed to stay for half of the three-hour session. “They wanted to test my attention span and whether or not I would interrupt the class.” Soon, she had proved her worthiness and Wolfinbarger invited her into the full group, where she stayed into high school. “It’s just what I did,” says Dunbar, expressing matter-of-factly how integral art was to her.

Still, everyday life intervened. She married, had two sons, divorced, supported herself and the boys by working as a legal secretary, and battled and eventually overcame a long-term illness. Through it all, however, her love of making art stayed true. “I never stopped painting,” she says.

Untitled (detail of a painting in progress) | Oil on Board | 2023

Then, Dunbar continues, around 1998, “My boyfriend at the time made me aware of the Art Students League of Denver, and he astutely said, ‘You need some joy in your life.’” She visited that institution and signed up for a “professional studies class” to be taught there, “through some miracle,” by none other than Quang Ho, the Vietnamese-born, classically trained painter who, at the age of 12, emigrated to America with his family, gained professional recognition in his teens, and went on to become one of the nation’s most widely respected realist painters.

Pepper | Oil on Board | 12 x 9 inches | 2021

“He is a consummate person, artist, and teacher,” she says of the two years she studied intensively with Ho, along with two more years of occasional workshops she took with him. “I went into his class with a skill set I had developed as a child. Quang taught us everything he knew, and he knows a lot. He told me, ‘Work on your art, the rest will follow.’ And I believe that has held true for me.” She also studied extensively with master artist Mark Daily, another invaluable guide.

Rain on Windshield: Open | Oil on Board | 30 x 30 inches | 2020

Success has, indeed, followed for Dunbar, but she never takes it for granted. Once her boots painting’s destination had changed, she found herself “missing a standout painting” for the Coors. So, she spent “an average of 10 easel hours a day, seven days a week” right up to her deadline to complete A Little Bit of Happy, a closeup of exuberantly tangled sunflowers she spied in front of a house late one afternoon while running errands in her neighborhood east of Denver. Like all her compositions, she worked it out on her computer and then set about meticulously painting the 24-inch-square image using a grid system, painstakingly executing each square freehand. (As a design motif for this article, Dunbar has graciously shared one completed upper strip of such a grid for a yet-to-be-titled painting-in-progress of two leafless treetops.)

Rain on Windshield: Rosie’s Diner II | Oil on Board | 24 x 24 inches | 2021

Lest aficionados think this methodical approach antithetical to the artistic process, all they need to do to lay such doubts to rest is carefully consider one of Dunbar’s actual finished canvases. Up-close, each area of what may initially seem to be an almost photorealistic rendering becomes a marvel of abstract painterly execution. Zoom in on the water in Rain on Windshield: Rosie’s Diner II, for example, and witness something akin to a Mark Rothko canvas in miniature. “Way back when I was studying with Quang Ho,” Dunbar says, “he used to say that every element of a painting should have its own shape, its own identity.” And her meticulous process ensures that even the most ordinary-seeming droplet referenced in the painting’s title is simultaneously unique and an integral part of the whole.

Rain on Windshield: Rosie’s Diner IV | Oil on Paper | 6 x 6 inches | 2022

Such is the wonder Dianne Massey Dunbar finds in the quotidian world. And, ultimately, her artistic talent expresses its power through her ability to share such joyous visions with the viewer.

Dunbar’s work is represented by Gallery 1261 in Denver, Colorado; Broadmoor Galleries in Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Edward Montgomery Fine Art in Carmel-By-the-Sea, California.

Rain on Windshield: Open | Oil on Board | 30 x 30 inches | 2020

No Comments