02 May Hill Country Harmony

Jim Vangilder always drives slowly to the front door of his house. Even though he could easily course the mile-long route from the state highway turnoff to his entrance in minutes, he purposely takes his time because he wants to see, yet again, the Texas land on which he and his wife, Marsha, have built their new ranch house. When they purchased the 175 acres of land near Weatherford, Texas, some of the property once housed natural gas wells, which required service road access. But, as he and Austin-based architect Chris Davenport began plotting the new house’s location, the land itself and the sites along it became a primary concern.

The entry, reached upon crossing a bridge and dry creek bed, feels akin to entering an outdoor room.

“The original service road winds back and forth along the contours of the land,” says Vangilder, a retired lumber industry executive and now a champion cutter in the herding-related horsing sport. “We laid out the approach to the house so that it passes three ponds linked by waterfalls, or what we call in Texas ‘tanks,’ some of them with ducks floating on the surface. You pass some of the cattle we raise, the calves and the bulls playing around on the fields. It feels good to follow this road slowly, and it makes the property feel so much bigger than it even really is. I enjoy the drive in and the drive out.”

Davenport was adamant about preserving many of the large oaks so that the ranch house would appear to have been a part of the land for a long time, as if it had aged along with the trees. “You come up the drive to the house,” Davenport says, “and you shed the cares of the world. The closer you get to the house, the more intimate the approach feels.”

A large-scaled bronze and amber lantern hangs in the foyer, creating a soft glow at night. The space feels like a glass box. Steel doors and windows provide minimal frames with maximum transparency.

As a native Texan with his architecture firm based in Austin, Davenport knows the state’s ethos, its people, and the kinds of houses many now favor. While the Vangilders wanted a spacious home to accommodate themselves and their visiting daughter, they also wanted nothing pretentious or ostentatious about the design. The resulting one-story house gracefully vaults across the land, taking in views of an 8-acre lake on the property, stocked with bluegill and bass, and the vistas of the open, undulating land.

“The story of residential architecture in Texas is that people like to use practical materials with little added ornamentation or details that might seem fussy or fancy,” Davenport says. “People here know their history, and when they build, they often build — as these clients have — a legacy house, something that gets passed down to generations.”

The exterior stonework and reclaimed wood siding were incorporated into the house’s great room, whose focal point is a massive fireplace. Charlotte Carothers, the interior designer, designed custom furniture to scale with the vaulted ceiling. The sofas are covered in Moore & Giles leather. The cobalt blue lamps provide pops of color.

The directive from the clients was for a one-story ranch house that was rustic in appearance but comfortable in living. “My wife was okay with the rustic idea, but she insisted that she didn’t want to live in a barn or feel like she was living in one,” Vangilder recalls with some humor. Davenport designed a house in a style he refers to as “Hill Country Modern,” a moniker referencing its Texas locale and its aesthetic, which is characterized by uninterrupted walls of floor-to-ceiling windows, a central open living plan, and precise rectilinear forms.

A custom black metal hood over the kitchen range echoes the stovepipes found in old cooking equipment.

Davenport and the Vangilders chose a grade of sandstone known as Arkansas field stone for the chief structural material. “My wife and I wanted something darker than typical Texas-grade limestone,” says Vangilder, “and this variety has a wide range of browns and grays, with some black stones.” Before committing to the material, however, Davenport had the builder, S&B Engineers, try it out by constructing a well house out of the stone on the property. “We really liked the look of it,” says the homeowner, “and there is still not a visitor to the house who doesn’t remark on the stonework.”

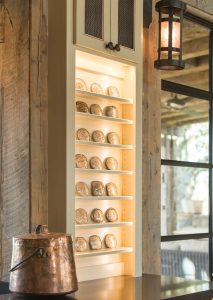

A wet bar adjacent to the kitchen was the perfect place for a built-in display case, highlighting the homeowner’s awards in the show horse arena.

Indeed, assembling the stones on the long house was akin to working a giant jigsaw puzzle. An expert team of some 20 workers chiseled, cut, and sawed each stone, dry-stacking them in place. Vangilder was so entranced by their collective skill that he spent many afternoons sitting in a chair on site, watching his house come into being.

The house’s other conspicuous material is wood — all of it reclaimed. Davenport explains that finding this much reclaimed Douglas fir from any single source was a challenge and that combining wood from different sources results in a patchwork of hues. However, he found and worked with Montana Reclaimed Lumber, whose specialty has been sourcing wood from old barns and other structures. The resulting beams, trusses, columns, facings, and additional expanses wear an appealing patina of age. “You look at the beams inside, and you see tendon notches in them,” says Davenport, “and those details speak a story. There’s a history to the wood.”

While much of the home’s wood once served a structural purpose in prior structures, some of it was sufficiently stressed and required engineers to carefully assess each board for durability. “Engineering becomes part of the process of selecting wood for trusses and beams. You have to know the structural capacity of the beams before using them for support.” A simple, clear sealer was applied to these reclaimed boards to preserve them further.

Reflecting the homeowner’s love of the Old West, the study’s walls are clad in a chinked siding, made from reclaimed wood and reminiscent of old settlement cabins.

Although Jim and Marsha are the only full-time occupants — though they receive frequent visits from their daughter, Grace, an interior designer — they wanted a large house with demarcated living areas. “Every time I walk into the big great room,” says Vangilder, “I am blown away by its look and feel. Everything about that central space, which contains the living and dining areas and kitchen, feels comfortable and inviting.”

The interior designer for the project, Charlotte Carothers, solved one of the couple’s requests for a large dining table. She took the Vangilders to Round Top Antiques Fair, the now internationally known event in Texas, where she introduced them to a Michigan dealer known for salvaging materials from abandoned railroad bridges. “I designed a dining table able to seat 12 out of the reclaimed oak wood he had,” says the Austin-based Carothers. “The dealer drove it down to Texas, and after we assembled the legs and put on a wax finish, it was all ready.”

The rear porch is supported by 8-by-8 foot reclaimed timbers; steel plate connections were used to accommodate the irregular shapes of the wood and the metal was pre-rusted for appearance’s sake.

Anchoring the great room are separate sleeping quarters — a large primary suite and an equally ample suite for the Vangilders’ daughter. Additional bedrooms are housed in a separate guest house, with a central corridor in the main house linking public and private areas.

Furnishings throughout are classic in style, durable, and muted in tone, keeping with the exterior architectural and landscape hues. As Carothers emphasizes, “I always visit the site of a client’s house often, and I did that here, taking in everything from the colors of the rocks on the land to the shapes of the land. If a designer doesn’t visit the site of a house in progress, there will be mistakes.”

The bed’s headboard in the primary suite is tufted Belgian linen.

Although Vangilder is a champion cutter and horse breeder, he is modest about the array of medals he’s won in the sport. Davenport noticed these accolades and convinced Vangilder to incorporate a built-in display case. That lit cabinet, situated near the kitchen end of the great room, features scores of Vangilder’s gold belt buckle awards. “Jim is not a brag-worthy kind of man,” says Davenport, “but I thought it was important to bring something this personal inside the house.”

Even though the house is long finished, the Vangilders are far from jaded about the experience of living in their residence. “I like that it looks as if this has been here a long time,” says Vangilder. “From the start, during the planning process, I wanted this house to fit the land, to look like it naturally belonged here.”

High, clerestory windows in the primary bath keep the room flooded with natural light while maintaining privacy.

Davenport, too, is admittedly proud of his work on the house. “My job as an architect is to build a structure, with a roof over it, in which people can live and thrive. It’s home already; full of memories with future ones to come.”

No Comments