02 May Lavender Shadows

Howard Post’s sense of Tucson is steeped in his bones. As the often-cloudless, solid sky clears a space for contemplation, shadows slide across the desert. His oil paintings reflect a profound understanding of the land. The horses he paints are the horses of his life. As a rodeo roper, the closeness of his equine subjects feels like his own skin.

“I respond to imagery that excites me,” says Post, who was born and raised in Tucson and has lived in Arizona for most of his life. “The bright sun and the landscape have always been part of my work.”

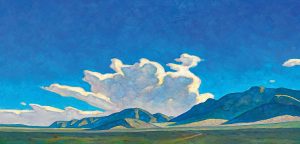

Ranch on the Border (above) | Oil | 15 x 40 inches

In his painting Rodeo Cattle, Post’s perspective brings the viewer into the pen, into the agitated movement of waiting. The steers’ shadows crowd, making lavender-blue connections between them. Corral posts deepen the image with geometric patterns that engage the eye and calm the mind; these two competing emotions balance due to the color palette and intricate composition.

Post has participated in rodeos and worked with horses throughout his life. “I was a high school champion and on my college rodeo team,” he says, adding that he competed professionally for three years. “I continued that in amateur events and in the Senior Pro Rodeo for a few years. It’s always been a part of my life.”

His paintings ring true to the desert, and his colors honor the landscape he loves.

For Tomorrow’s Fence Crew | Oil | 36 x 44 inches

“The best way to describe Howard Post is as an original voice of the New West, and he has been for 50 years,” says Mark Sublette, founder of Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson. “In the 1970s, he discovered the clearest way to find his voice was to use the imagery that he grew up with and to look at it from a new perspective.”

This perspective includes both the height from which he depicts his subjects and the fact that he tends to focus on things most people don’t notice.

“He wants to document what he sees, cowboys at work, a little rodeo,” Sublette says. “He sees the world in terms of two cowboys talking, a dog on the side with a trailer in the background. He does all this with a modern sensibility and with colors that are only his.”

The color harmony in Post’s work helps convey the emotion of the scene. Sublette adds that the artist “throws out the color wheel and uses the ‘Post wheel.’ A horse with sweat on it, and if the light is just right, it actually does look purple.”

Three Mustangs | Oil | 18 x 36 inches

Post documents his life through his art, and his knowledge of Western culture brings an authenticity to his work. “There’s a thread in all his paintings — a familiarity with the culture, environment, and his time,” Sublette says. “He’s not trying to capture images from the 1890s. He wants to paint what he sees in his backyard. Those corrals are a thing that’s always in his mind. There are themes that resonate so deeply and so thoroughly — for Monet it was lily pads; for Dixon it was clouds; for Post it’s his corrals.”

Through his art, Post seeks to provide a new perspective on the region, blending traditional subjects with his signature approach to painting. “A lot of the time, I’ve come back to certain subject matter,” Post says. “I’ve always wanted to paint the West but not the cliches. I had contemporary art exposure in art school — artists like [Richard] Diebenkorn and Grant Wood. I wasn’t trying to imitate them, but it influenced my own style.”

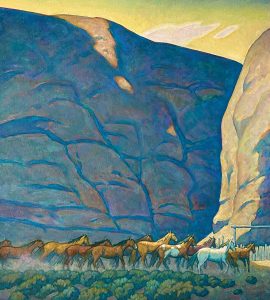

Canyon Catch Pen | Oil | 36 x 32 inches

He also worked in a studio at an advertising agency after college, which sometimes comes across in his steady, close-up focus on subjects. In his painting For Tomorrow’s Fence Crew, Post isolates each fence, giving them each a sense of portraiture, a personality. Some lean, others sway. The sunset in the background speaks of the next day’s work. The uneven posts, worn with time and weather, line up behind a wire like friends in a movie queue waiting for the doors to open.

“The strong sunlight in Arizona creates strong shadow patterns,” Post says. “So, shadows play an important role in my composition. The shadows become something in and of themselves. I like the effect when sunlight hits the shadows — there’s an edge quality, and I often try to portray that.”

The Red Gate | Oil | 18 x 36 inches

Early in his career, Post tried to paint the landscape with a more literal eye. He’d take his camera out, shoot tons of pictures, and then go back to his studio to paint. But through the years, he learned it wasn’t necessary to be literal. Instead, he could paint the things he loved just the way he saw them.

Beau Alexander, owner of Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Pasadena, has represented Post for eight years. “It’s important to look back at the art of the American West,” Alexander says. “If you look at the 1980s, there’s an emergence of artists who represent the culture through their imagery and their outlook. They were not representing history; they were representing the West through their eyes and through their own interpretation. Howard Post grew up doing rodeo; he knew those things and put those things in his paintings.”

Canyon Ranch | Oil | 24 x 48 inches

According to Alexander, Post’s graphics and bold shapes capture a unique feeling of the West. “The greatest artists show us their interpretation of things, not mimetically, but through their own perspectives and experiences. Howard is a trained artist. He was a teacher. He knows how to work color. And when an artist knows how to work values, he’s at a level where he can depart from realism and still make it true to life.”

Post often uses objects, poles, corrals, and fences to highlight the contrast between man and nature: the boundaries that show up every day and go unnoticed for the most part. “Those structural objects represent multiple things, man’s input on nature, yes, but he’s also using the corrals for compositional purposes,” Alexander says. “He uses them in a way that enhances the painting. He’s leading your eye in a way he wants it to be led. It’s like a road map with those corrals. It’s very biographical, and his work has an authenticity that doesn’t exist in other artists of the West because he grew up in it.”

Post says he loves painting the old corrals that are right down the road from his former home. “They’ve been around for a while and have a lot of character,” he says. “I’d visit with them for a long time and try to find different approaches to painting them. I still have an affinity for them. I grew up on 30 acres, and we had corrals made out of wood. My job was to repair those old corrals — we didn’t ever build new ones — so they have quite a character. That stayed with me my whole life.”

No Comments