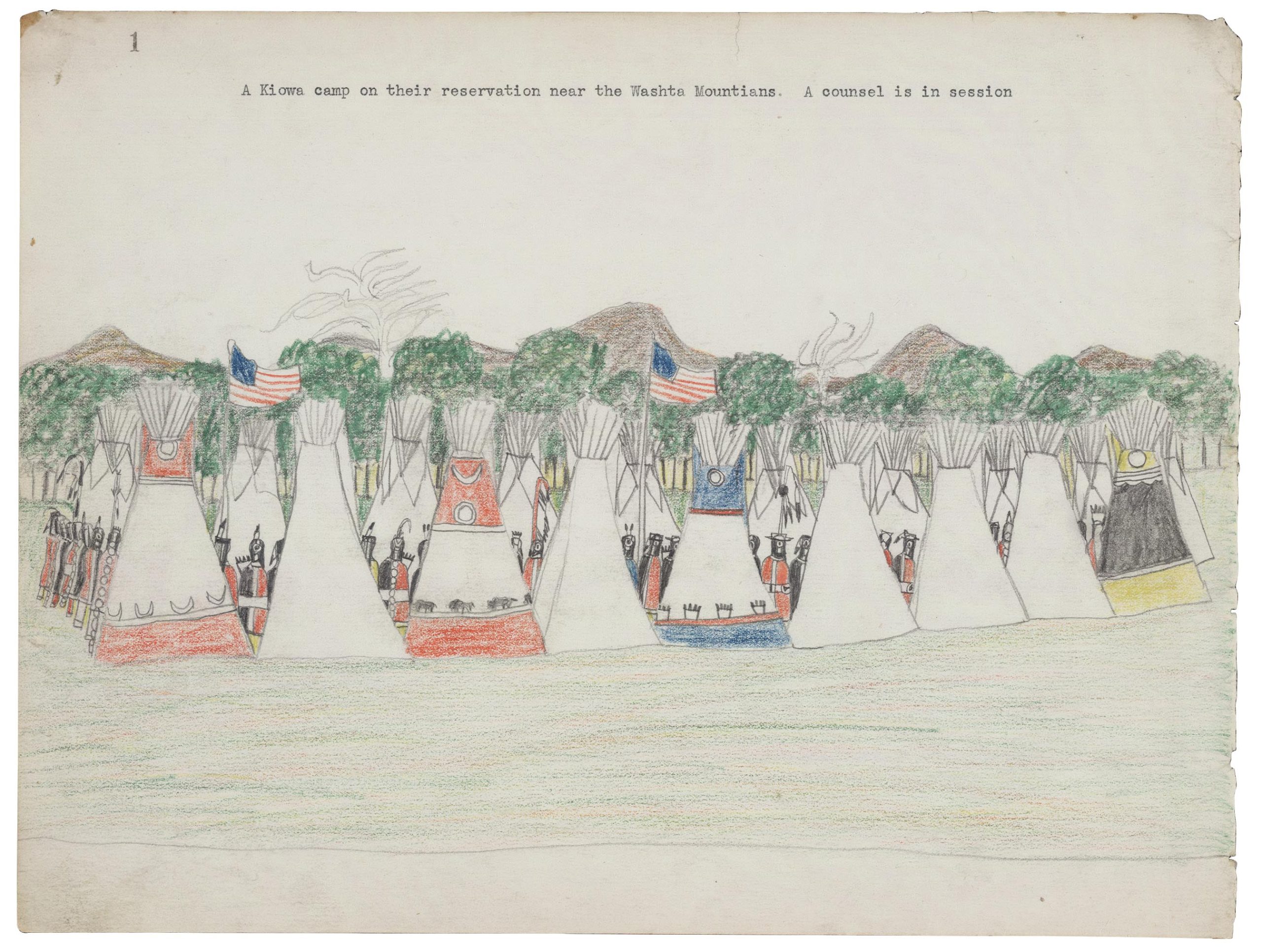

02 May Perspective: Etahdleuh Doanmoe [1856 – 1888]

Of all the interactions between Native Americans and the U.S. government in the late 1800s, the experience of 71 Southern Plains warriors at Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida, was among the most unusual. The men were prisoners of war, but their three years of captivity also represented an experiment in forced acculturation, which led to the establishment of the first off-reservation, government-run boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Indian Prisoners Upon Arrival at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida (Doanmoe second from the left) | Photographer Unknown | Albumen Print | 1875 | Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 23, Folder 745, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

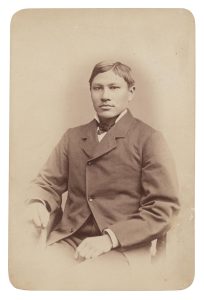

Among the prisoners was a Kiowa man named Etahdleuh Doanmoe. During his short lifetime — he succumbed to illness at age 32 — he was a hunter, warrior, prisoner, student, recruiter of Kiowa children for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, farmer, and Presbyterian missionary to his people. He is most widely known, however, for the drawings he produced at Fort Marion and the way these images document a remarkable slice of Native American and American history.

Etahdleuh Doanmoe | Photographer Unknown | Albumin Print on Card | 6.5 x 4.5 inches | 1860 | Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 23, Folder 729, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Etahdleuh (pronounced Eh-TA-dlee-uh) was known by his Kiowa name among his captors, fellow prisoners, and even other Kiowas when he eventually returned to his home territory in what later became Oklahoma. Retired museum director and curator Phillip Earenfight notes that this was a departure from the convention of referring to Native people by English translations of their traditional names. Etahdleuh is variously translated as “boy hunting,” “boy coming out,” or “we are seeking boys” — likely a reference to the fact that his mother, a Mexican, was captured by Etahdleuh’s Kiowa father in a cross-border raid.

The Night of the Surrender and After They Had Given Up Their Arms and All War Material and Had Received Rations the Indians Had a Dance to Which They Invited Capt. Pratt. and His Interpreter, Phil McCusker. The Incidents of That Dance Are Among the Most Vivid in My Memory. There were 72 Loges and About That Many Warriors Beside Their Women and Children, about 200 in All. I Had Eight Indian Scouts, the Interpreter, Two Wagons with Colored Teamsters and Three Tents. (See on One Side) | From A Kiowa’s Odyssey , page 5 | Graphite, Colored Pencil, and Colored Ink on Paper | 8.44 x 11.188 inches | 1877 Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 31:25, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

In 2007 and 2008, as then-director of the Trout Gallery, the art museum of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Earenfight conceived and curated a traveling exhibition based on a sketchbook of Etahdleuh’s drawings made in 1877. A Kiowa’s Odyssey: A Sketchbook from Fort Marion, and an accompanying catalogue, examined historical, cultural, and artistic aspects of the 33-page sketchbook, its maker, and the circumstances in which it was produced.

The Party Remained at Fort Leavenworth Two Weeks and Were Taken Out of the Guard House Daily for an Airing | From A Kiowa’s Odyssey , page 13 | Graphite and Colored Pencil on Paper | 8.375 x 11.188 inches | 1877 The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, 190.7.11.3v

Etahdleuh’s early years unfolded with the rhythm of his tribe’s movements, a nomadic life of following and hunting bison. But as American settlers on the Southern Plains increasingly encroached on the tribes’ traditional hunting grounds and the U.S. government began forcing Native people onto reservations and exterminating the bison, warriors from the impacted tribes put up resistance, attacking settlers and the U.S. military charged with protecting them.

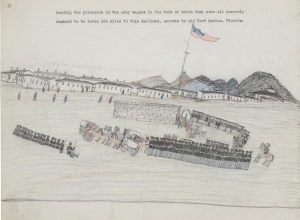

Loading Prisoners in Army Wagons From A Kiowa’s Odyssey, page 9 | Graphite and Colored Pencil on Paper | 8.44 x 11.188 inches | 1877 Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 31:9, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

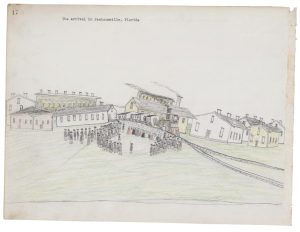

In the winter of 1875, a group of prominent warriors and their followers — exhausted, starving, with their camps burned and their horses killed by the military — surrendered. To prevent them from inciting further rebellion, the U.S. War Department exiled some of the men. These Comanche, Kiowa, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Caddo prisoners were transported in shackles to Florida, covering 1,000 miles by wagon, steamboat, and train. The youngest, at 19 years old, was Etahdleuh.

The Arrival in Jacksonville, Florida | From A Kiowa’s Odyssey , page 17 | Graphite and Colored Pencil on Paper | 8.44 x 11.188 inches | 1877 Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 31:17, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, the officer in charge, decided to use the warriors’ captivity as an opportunity to assimilate them into American life — mold them into English-speaking, productive Christians. Soon after settling into Fort Marion, the prisoners were allowed to move freely around the highly fortified 17th-century former Spanish fortress. They were taught English, visited the nearby ocean, and were enlisted in a variety of jobs, including clearing land, sawing lumber, toting baggage for the railroad, and making bows and arrows for tourists. Pratt paid the prisoners for their work to familiarize them with capitalism. They could send money home to relatives or purchase items at the fort’s storehouse.

A Kiowa Banquet in the Good Old Days Back Home | From A Kiowa’s Odyssey, page 24 | Graphite, Colored Pencil, and Colored Ink on Paper | 8.44 x 11.188 inches | 1877 | Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 31:24, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Drawing was among the primary activities for Etahdleuh and many other men. While Pratt encouraged them to draw their experiences at the fort, some warriors also visually documented their surrender, the long journey, and occasionally their earlier life. Using a sketchbook was an extension of the tradition of Plains ledger drawing, in which warriors documented battles, buffalo hunts, and other aspects of their lives, drawing in ledger books traded or left behind by European Americans. Before the virtual eradication of the bison, they had created such drawings on hides.

Young Kiowas Dressed for a Ceremonial Visit | From A Kiowa’s Odyssey, page 22 | Graphite and Colored Pencil on Paper | 8.44 x 11.188 inches | 1877 Richard Henry Pratt Papers, MSS S-1174, Box 31:22, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

At Fort Marion, Etahdleuh and others used their earnings to buy good quality sketchbooks, colored pencils, and ink. The style of their drawings soon diverged from the flat, two-dimensional look of traditional ledger art in which figures are generally placed on a minimal background. Now, they drew views of the fort, its chapel, the town of St. Augustine, and neat rows of fellow prisoners in army uniforms — part of Pratt’s program of using military-style discipline to acculturate the men. Among Etahdleuh’s drawings are scenes of a Kiowa camp with a chiefs’ counsel in session and images of the warriors’ journey by train and boat.

Although it’s unclear whether the prisoners received any formal instruction in the European approach to art, it is known that at least two American artists visited the fort. One was an illustrator for Harper’s Magazine, which published an article on the Fort Marion prisoners appealing to readers hungry for stories and pictures of American Indians. The prisoners also had access to newspapers and photographs. “There’s no question that Etahdleuh’s work reflects a solid understanding of Western pictorial convention — warm colors in the foreground, reduction in scale, linear perspective, and color blending,” Earenfight says.

Yet, when Etahdleuh and other warriors drew pictures of traditional life on the Plains, they tended to return to the flat, two-dimensional ledger style. “They were consciously switching styles,” Earenfight says. “They knew their drawings were for sale. Were they being told by Pratt that this is what tourists wanted, or did they just know that? Etahdleuh, in particular, had two styles, which strikes me as fascinating. We don’t know what the motivation was.”

Joyce M. Szabo, professor emerita of Native American Art History at the University of New Mexico, points out that Etahdleuh was one of the only prisoners to use a wash of color, along with ink and colored pencil lines. His was more of a “painterly approach that almost looks like a dry brush technique,” Szabo says.

While most of the prisoners’ drawings were sold as individual pages, the complete sketchbook featured in A Kiowa’s Odyssey had been a gift from Pratt to his son Mason, who took it apart and reassembled it as an album. Each image contains a typewritten caption at the top, which Pratt added.

Another complete Etahdleuh sketchbook was purchased at Fort Marion in 1876 by a wealthy visitor from Pittsburgh. In 2018, it was sold at auction in Dallas. In January 2024 the sketchbook, which Earenfight describes as “spectacular,” was part of a Sotheby’s auction where it was estimated to go for between $200,000 and $300,000. Instead, according to Sotheby’s, the sale “more than doubled the world record price for a piece of Plains ledger art,” and it sold for $825,500.

Despite the fact that many of the warriors chose to return home after their incarceration, Pratt considered his acculturation experiment a success, with Etahdleuh as his “number one Indian.” Pratt appointed him Quarter Master Sergeant, in charge of food and other stores, and Etahdleuh served as next-in-command when Pratt was absent. As an excellent English speaker, he was among a group of former prisoners sent for a year to the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Hampton, Virginia, a school for recently emancipated African Americans, from whom the Native American students were segregated.

Pratt also took Etahdleuh along as he visited government officials in a campaign to establish a boarding school where he could employ his acculturation model on Native children. Obtaining the use of a former military post, he opened the Carlisle school in 1879. Etahdleuh, among the first students, was sent to his Kiowa people in Anadarko, Oklahoma, to bring back children as students. Among the girls who returned with him was the teenage niece of one of Etahdleuh’s fellow prisoners at Fort Marion. At Carlisle, her name became Laura Toneadlemah, and upon her graduation, she and Etahdleuh were married at the school.

Etahdleuh and Laura returned to Anadarko, where the U.S. government paid him to continue influencing parents to send their children to the school. There, the couple had a son, who died shortly after birth. Etahdleuh also began farming, but his health, which had been tenuous, declined. He and Laura traveled back and forth between Oklahoma and Carlisle, with Pratt paying for Etahdleuh’s medical treatment. A second son was born in 1886 and named Richard Henry Doanmoe in honor of Pratt. Two years later, the family returned to the reservation, where Etahdleuh took on the role of missionary. But his health grew worse, and a few months later, he died.

From the end of Etahdleuh’s schooling through the rest of his life, the young Kiowa and Pratt kept up a correspondence. While Pratt held an unequivocally paternalist, condescending view of Native people, Earenfight points out that there was also an emotional bond between the two men. “It was a complicated relationship. Pratt is easily pigeonholed and made one-dimensional, but there was a level of humanity in him that a lot of people don’t want to recognize,” Earenfight says.

This humanity coexisted alongside Pratt’s goal with all his charges: to “kill the Indian in him and save the man,” an attitude described as cultural genocide. For Etahdleuh’s part, much of his short life, including his drawings, reflected his experience straddling two very different cultures. “You get a sense of someone trying to live in two worlds,” Earenfight says. “He was trying to find his way in a complicated world.”

Gussie Fauntleroy has written about art, architecture, design, and other subjects for almost 35 years. She’s the author of three books on visual artists.

No Comments