10 Sep In the Studio: From Intrigue to Discovery

A few minutes from his home in Prescott, Arizona, painter and sculptor John Coleman strides over a bridge, where a wash runs below, to his art studio. A large fir door heralds his destination. Once inside, a stone fireplace sits front and center with several sets of moose antlers and a taxidermied bison that seems to watch over the place.

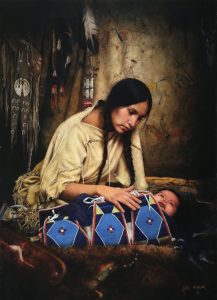

Mother’s Blessing | Oil on Canvas | 48 x 34 inches

“My life is about history and mythology,” Coleman says, as he walks around his workspace. “The Native Americans are analogous to my life, even though I’m not an Indian, I just love the history. I focus on the time of Lewis and Clark, and the obscure tribes of the Upper Missouri.”

Coleman and his companion Henry, a Bouvier des Flandres, take a quick coffee break.

Coleman’s studio is like a time machine, as most of his work centers on the era before reservations were established. Taxidermy, patterned blankets, painted hides, and buckskin dresses — part of the wardrobe used for his models — decorate the painting studio. Half are antiques, and the other half were re-created for Coleman, including the headdress of Mato-tope, a Mandan war chief, who died in 1837. The headdress sports turkey feathers (originally it would have had eagle feathers), split horns, and the knife that represents the battle he fought, in which he charged the Assiniboine tribe and earned the name Four Bears.

The artist’s painting studio was built to take advantage of the northern light and is kept separate from his sculpture studio

Coleman’s interest in this period of history has also driven him to study the works of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, the first artists to paint the villages along the Missouri River. In fact, he created a series of sculptures based on their works.

From a bird’s eye view, one sees how the studio nestles into its environment.

Coleman walks to the back room where he creates his sculptures. Shelves laden with busts in process and finished pieces line the walls. A large mirror behind his sculpting stand allows him to see all sides of a piece and to observe the work in progress from a new perspective. “Human beings are wired to understand differences for a few moments, and then the brain considers them irrelevant and lets them go,” Coleman explains. “It’s like bad odors; after a while, you can’t detect them anymore. When you’re looking at something, your vision does the same thing. The mirror flips it and lets you see it fresh again.”

More than 4,000 books make up Coleman’s reference library, located just off his painting studio.

Coleman recently completed a body of work for a show opening November 14 at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, and plenty more are underway in the studio. He moves to his newest sculpture. “After I did a Mother Moon clay bust — the moon is the female and powerful — I decided I’m going to do a Sister Moon,” he says.

Coleman works on He Who Jumps Over Everyone, a clay sculpture based on an 1830s Crow Chief whose portrait was painted by George Caitlin. This sculpture will be included in a show at Legacy Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, that runs through November.

To begin a new piece, Coleman sketches the figure in clay. “Everything I do comes to me through a story,” he says. “My motivation is to tell a story that comes out of a metaphor. I don’t think of myself as creating objects. I think of myself as creating storylines.”

A photo taken from Coleman’s office loft shows his painting studio below. He’s surrounded by a large collection of wardrobe items — some re-creations and some antiques — that he uses for reference in his paintings and sculptures.

Coleman started his career as a young artist painting and drawing, but he then took 20 years off to raise his family. When he came back to creating art, sculpture lured him. “The idea of being an artist always struck me as a destination. That was my main goal. The practical aspect of sculpture is that it’s done in editions,” he says. In this way, he can create one sculpture and still have 35 editions to sell. “I had an advantage because I wasn’t a starving artist and could afford to make bronze sculptures,” he adds.

Through his work, Coleman invites the viewer to participate in the exploration of American mythology. Here, he stands before an oil painting inspired by the ancestral Crow people.

Currently, he’s working on a bust of Crazy Horse. Using Plastiline, a light brown, wax-based clay, he pinches off a small piece and warms it in his hands as he works with it. The face is detailed, with lines marking a meditative expression. It seems nearly finished; the hair and headdress have yet to be added. But for Coleman, it’s just the beginning. “Crazy Horse had specific things in his personality that I’ll address in the sculpture itself, but I always start with the anatomy,” he says. “It’s not as important to have a model if you have a good idea of anatomy. It’s like creating a particular kind of Gumby. I can create something very believable and dress it from my own wardrobe or from a photograph. In a painting, it’s much more important to have a model.”

Coleman goes back and forth between his painting studio to his sculpture space while working. When one piece gets to a point where he needs to think about it, he may move to the other studio, or he may walk back to his house and take a break.

The Oracle II | Charcoal on Paper | 65 x 39 inches

His artistic intention is to use a kind of cultural shorthand. “I want to create enough information to bring the viewer along. I never have any other goal than that,” he says. “I want to convey a tribal understanding of mythology. These symbols mean similar things in many cultures. Circles are feminine; squares are masculine. As an artist, I bring these things into play and can tell a story that becomes the viewer’s story.”

No Comments