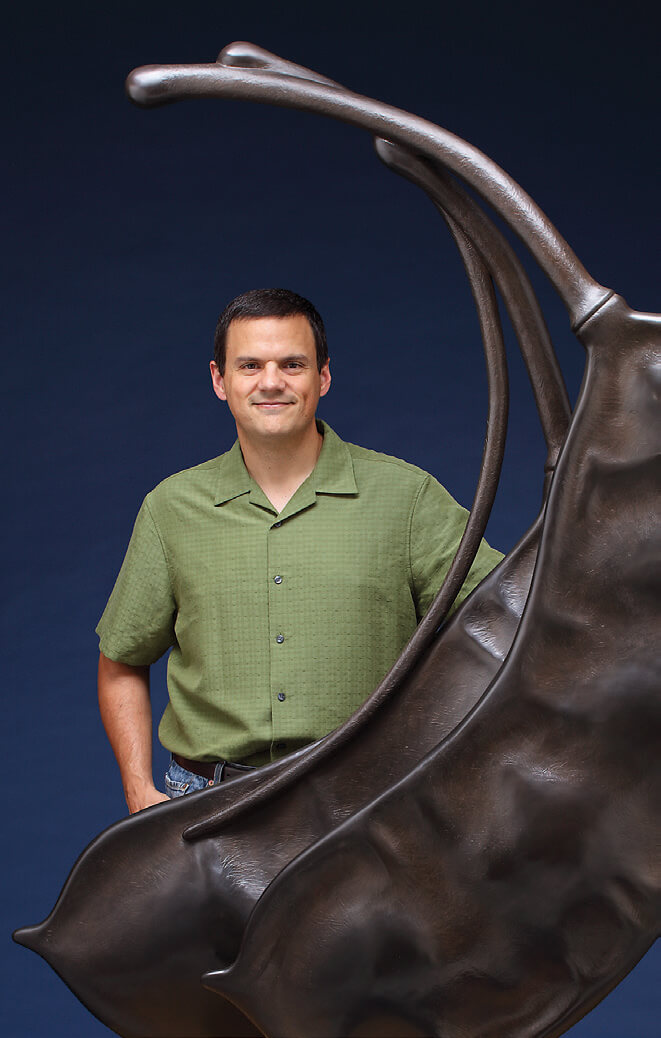

08 Sep Artist Spotlight: Tony Hochstetler

Tony Hochstetler celebrates the natural world’s small-scale wonders in bronze sculptures that combine faithful realism with elegant Art Nouveau, and many of his works also fulfill practical purposes. His Fruit Bat Sconce, for example, serves as a dramatic home lighting feature, with one wing of the life-sized flying mammal wrapped around a green glass globe designed by the artist and hand-blown in the Czech Republic. “I’ve found that many advanced collectors might not have room for another traditional piece,” observes the Colorado-based artist. “But they can make room for something functional. Primarily, though, I just really enjoy making them.”

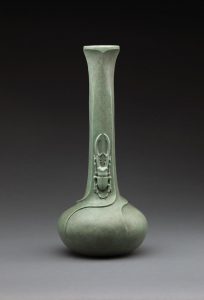

Beetle Vase | Bronze | 15 x 6 x 6 inches | 2018 | Edition of 15

He discovered that joy in his twenties. But Hochstetler realizes that he’d been preparing for this passion since his boyhood in rural northern Indiana. In the 4-H Club, he immersed himself in entomology. “The ponds of our farm were full of frogs, toads, and salamanders,” he says. “I was always out gathering toad eggs, putting them in jars, watching them hatch, and raising the tadpoles.” In high school, he concentrated not only on the life sciences but also on industrial arts, fabricating practical objects from wood and metal.

In 1984, at age 20, Hochstetler spent the summer helping his uncle, professional potter Ed Schrock, set up a new studio in Colorado Springs. “I took to learning pottery pretty quickly,” he says. He also took a shine to Shannon, a young woman who lived two hours north in Loveland, home to some of the nation’s most respected sculpture foundries. At summer’s end, he moved closer to her, working at Art Castings of Colorado, a full-service bronze foundry.

Fruit Bat Sconce | Bronze, Glass, and Quarter-Sawn Oak | 36 x 12 x 18 inches | 2020 | Edition of 9

“About six weeks later, I brought some wax home and sculpted my first piece,” Hochstetler says. Over the next three years, he worked in many departments at the company before leaving to sculpt full-time. He and Shannon now live in Frederick, 15 miles north of Denver’s suburban fringes and half an hour from Loveland.

Hochstetler found himself gradually gravitating toward the elegantly sweeping lines of Art Nouveau, a style that also found inspiration in the natural world. Seeking absolute accuracy in his representations of animals, he relies on research and photos that he takes at the Denver Zoo and on the specimens he keeps in two “cabinets of curiosities” in his home studio. These include fossils, skulls, “a lot of dried insects,” seed pods, and, preserved in formaldehyde, such specimens as crayfish, seahorses, a small shark, and a Gaboon viper. He fashions sculptures directly in clay or wax and then cuts them into sections for efficient mold making, casting, and welding. He often still chases the welds himself, refining their edges, and then oversees the patina work before mounting each limited-edition piece on a base he’s designed.

The World on Her Back | Bronze, Black Granite, and Walnut | 16 x 16 x 13 inches | 2021 | Edition of 9

Now, having sculpted for 35 years, Hochstetler feels he’s established his well-defined “bio-diverse” niche within the fine art world. And he doesn’t plan to branch out into larger Western wildlife like bison, mustangs, or bighorn sheep. “A number of world-class sculptors are already doing those subjects,” he says with a chuckle. “I know where my interests lie.”

Hochstetler’s work is represented by Simpson Gallagher Gallery in Cody, Wyoming; Wilcox Gallery and Wilcox Gallery II in Jackson, Wyoming; Cheryl Newby Gallery in Pawleys Island, South Carolina; Bronze Coast Gallery in Cannon Beach, Oregon; and Grapevine Gallery in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

No Comments