17 Sep Painter C.W. Mundy

C.W. Mundy knows that a high level of proficiency and his ability to control paint can get in the way of creating an excellent work of art. When he sees this happening, he deliberately starts a “dog fight” with his own work. He forces himself to get into trouble, intentionally messing up an area of the canvas, then scraping it off and coming back to fix it. The result is inevitably more alive, nuanced, and fresher than it would have been. It’s a bit of artistic wisdom that stuck with Mundy when he first heard it from a revered painting instructor, Donald “Putt” Puttman, in the 1970s. But it’s something that can only be applied after decades of learning to paint.

Mundy has that time and experience under his belt. At 76, the Indianapolis-based artist has earned countless awards, a strong, appreciative collector base, and a reputation as an inspiring and generous painting teacher. Along with workshops, books, and instructional videos, he was honored in 2018 to serve as the inaugural artist-in-residence at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis, the world’s largest children’s museum. Jeffrey H. Patchen, who recently retired as the museum’s longtime president and CEO, calls Mundy a “one-of-a-kind artist-scientist-educator who brings together for children and their families the very best of the creative and technical processes of art-making.”

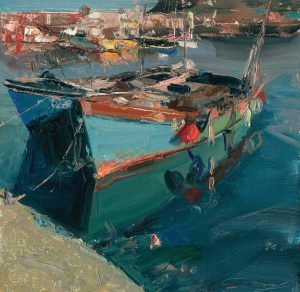

Boats at Mevagissey, Cornwall | Oil on Linen | 12 x 12 inches

Perhaps one reason Mundy relates well to children is that he shares their restless curiosity and need to explore new things. “I would be so bored if I did the same thing all the time,” he says in his thoughtful, good-natured manner. “I’m always looking at new ways to express paint.” This means viewers and collectors will also never be bored. Mundy’s easel at any moment may hold a landscape, seascape, cityscape, still life, portrait, or figurative work, and within any genre, his approach can range from textural and wildly impressionistic to realistic and precise. Sometimes he incorporates both ends of the spectrum in a single piece. “He’s never stopped experimenting,” says Lyn Letsinger-Miller, art historian and president of the Brown County Art Gallery Foundation in Nashville, Indiana. “I consider C.W. Mundy the preeminent living artist in Indiana right now.”

While Mundy’s favorite sources of inspiration include coastal and harbor scenes, most of his life has been spent in the landlocked Midwest. Born and raised in Indianapolis, he was the son of a home builder-turned-police officer and a mother who worked for Western Electric. The artist remembers sitting on his father’s lap at 3 or 4 years old and squeezing a muscled, tattooed arm while his father doodled and drew with his other hand. Mundy’s paternal grandfather was a cartoonist for The Denver Post, and Mundy was introduced to Disney characters on a neighbor’s black and white TV. By age 7 he was receiving praise for his drawings of Goofy and Pluto on cardboard cut from grocery store boxes. The posters, assigned by his Bible school teacher to keep the fidgety boy quiet, featured messages like, “Goofy says: Go to daily vacation Bible school!”

Schooner at Old Gloucester | Oil on Canvas | 30 x 40 inches

But drawing was not Mundy’s only creative outlet. His grandmother, a talented musician who played ragtime jazz piano for silent movies at a downtown Indianapolis theater, gave him his first musical instrument, an Arthur Godfrey ukulele. Soon he had a four-string guitar, and after high school, two full-sized guitars and a banjo. Throughout high school and college — first at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, and then at Long Beach State University in Los Angeles, where he earned a Master of Fine Arts — Mundy balanced music, art, and basketball.

In California in the mid-’70s, Mundy co-founded and played in a group called the Tarzan Swing Band, whose fusion of jazz, country, blues, bluegrass, and swing proved popular and took them on the road. The band was about to sign a recording contract with MCA Records when the fiddle player was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and died. Mundy was devastated — until he realized fate was nudging him onto a different path. “In the midst of depression because my dream of music was gone, God spoke to me in my heart and said, ‘You’ll be doing art,’” he says.

Fallen Warrior | Oil on Linen | 12 x 12 inches

In 1978 Mundy moved back to Indiana and shifted his primary focus. For 10 years he merged his artistic talent with a love of sports, forming a company called Champion Illustrated Sports and serving as the official illustrator for longtime Indiana University basketball coach Bobby Knight. Smiling, he guesses he’s the only artist to ever create a 5-by-7-foot hardwood basketball floor, which stands vertically, with blown glass neon letters spelling a coach’s name at each end and painted portraits of the players in between. His 3-D tribute to the Hoosiers was followed by many similar artworks commissioned by other top athletes and teams.

Then in the mid-1990s, a confluence of events inspired and launched Mundy into fine art. In Chicago, in 1995, he visited an exhibition of more than 240 Claude Monet paintings on view for the first time. “I came into contact with it on such a personal, passionate level because of the charisma and feeling Monet put into his painting,” Mundy remembers. At the same time, in reading about Monet, he was struck by how the French Impressionist approached the same subjects over and over, exploring them in paint and developing his distinctive style.

Point Lobos, California | Oil on Linen | 16 x 20 inches

Mundy’s first plein air painting trip to France, also in 1995, produced a body of work that began bringing him national attention. He earned Best of Show during the Hoosier Art Salon that year for a still life.

For the next 15 years, Mundy and his wife, Rebecca, whom he describes as an invaluable partner in his art career, frequently traveled and painted throughout Europe and the United States. The couple visited artists’ colonies and absorbed art history; Mundy studied the work of any artist, living or historical, whose painting he admired. Rebecca calls this period “the backbone of C.W.’s career.” Many of these journeys led to workingman’s harbors in Europe, England, or along the New England coast. Paintings from such places are among the artist’s most well known: wooden docks and venerable, often brightly colored vessels of all kinds, their simple shapes allowing for a play of texture and abstraction amid the shimmering aliveness of water.

Thinking of his passion for old wooden boats, Mundy concedes that although he is “really grateful to be alive in this generation, I wish I’d lived 150 years earlier — everything that’s handmade and handcrafted rubs my soul in a warm way.”

Also close to his heart and often on his easel are scenes of flowing water in mountain creeks or waves crashing on rocks along the California coast. Point Lobos is a particular favorite destination, where the visual stimulation of water is matched by the feeling of sun and wind on his face, the sound of the surf, and the smell of salty air. Similarly, changing light and weather on mountain peaks in places like Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park provide iconic imagery and the feeling of expansiveness that Mundy loves.

St. Regis Falls| Oil on Linen | 12 x 12 inches

Jim Ross, owner of James R. Ross Fine Art in Indianapolis, which has represented Mundy for years, has long admired the artist for the remarkable variety and quality of his work. “He also has an energy, drive, and work ethic that is scarcely matched by any other artists I can think of,” Ross says. Equally important, he adds, are Mundy’s gifts of teaching and mentorship with other painters, and his own continual desire to learn.

One thing the artist discovered at some point is the benefit of “painting upside down.” He almost always paints from life, but when he uses a reference photo, he may render the basic forms and then rotate the photo top to bottom. Painting something while looking at it upside down “tricks your mind and stops you from painting things,” he says. Instead, it forces him to express the colors, values, and abstract shapes he actually sees.

Likewise, a recent approach Mundy calls “3-D realism” is based on the way the human eye functions, with a central element in clear focus and the rest blurred. In Fallen Warrior, the viewer’s attention is drawn and held by sharp edges and reflected light on a broken section of a newly fallen tree, while the background forest is conveyed in soft focus.

Near Williams Creek | Oil on Canvas | 36 x 24 inches | 2021

Mundy’s nonstop exploration — “like Lewis and Clark,” he says — applies not only to visual art but to music as well. These days he plays private parties with members of a popular Indianapolis-based bluegrass band called the Disco Mountain Boys. He also has a newly released CD, The Impressionists, which features his “impressionistic” approach to the banjo and has song titles that all refer to art. In both music and painting, and life in general, Mundy’s mature years have brought an opportunity to release the tight clench of control and allow for a more relaxed creative approach. “I really paint for myself, in the spirit of the Lord and his guidance and direction,” he says. “When I really paint to please myself and the Lord, the conclusion can be different from what the original intent was, and I enjoy that.”

No Comments