17 Sep Perspective: Behind the Lens

You’d think the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” would be especially appropriate when describing photographer Edward S. Curtis [1868–1952]. After all, the portfolio that comprises his life’s work, The North American Indian, includes hundreds of images of Indigenous Americans. These photographs have been reproduced so often that we sometimes forget their origin. And the images have elicited strong opinions in support of and opposition to the artist’s work.

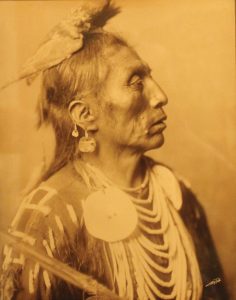

Medicine Crow | Goldtone | Size Unknown | 1909 | Peterson Family Collection

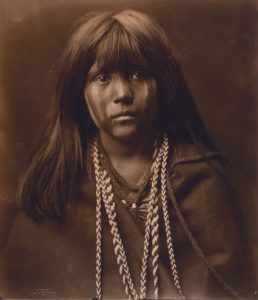

Take the photograph The Vanishing Race for example, with its line of mounted Navajos receding into the distance. The image epitomizes an entire mythology: the idea, circulated among academics and politicians from the turn of the 19th century and into the 20th, that contact with “civilization” would doom Native American culture. One glance at Curtis’s 1903 portrait of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, and you know you’ve seen it somewhere. And while looking at Curtis’s images of unmarried Hopi girls with the squash blossom whorls of hair at the sides of their heads, you recognize the appropriated reverberations in Princess Leia’s style in “Star Wars.”

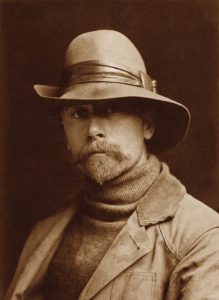

Self-Portrait in Felt Hat | Photogravure on Woven Paper | 10 x 7 inches | c. 1910

The North American Indian project became the largest anthropological enterprise ever undertaken in the U.S. Beginning in the 1890s, Curtis took thousands of photographs of Native Americans across the American West, yielding this monumental illustrated publication in 20 volumes.

An exhibition opening on October 19 at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West in Arizona, Light and Legacy: The Art and Techniques of Edward S. Curtis, offers the most comprehensive survey of Curtis’s work to date. The exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Tricia Loscher, the museum’s assistant director for collections, exhibitions, and research, and Tim Peterson, a trustee at the museum.

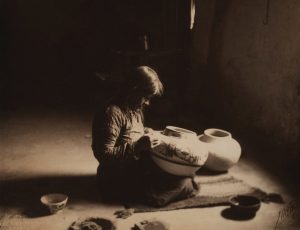

The Potter–Nampeyo | Platinum Photograph | 5.8125 x 7.4375 inches | Date Unknown | Peterson Family Collection

Peterson explains that the exhibition is organized in two parts. The first includes four portraits, one dwelling, and four to six additional images from each of the 20 volumes of The North American Indian. The second half focuses on Curtis’s various photographic techniques and materials, including bottles of the minerals he used to develop his prints and the camera he used. “On display,” Loscher adds, “will be photogravures; original copper plates; orotones, or ‘Curt-tones’; platinum prints; silver bromides; silver gelatins; cyanotypes; glass plate negatives; and recordings of Native music.”

Curtis’s photographs have generated countless opinions that run the gamut from praise to condemnation. To give two contrasting examples, Pulitzer Prize recipient N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) contributed an essay in the book Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian where he observes: “Taken as a whole, the work of Edward Curtis is a singular achievement. Never before have we seen the Indians of North America so close to the origins of their humanity, their sense of themselves in the world, their innate dignity and self-possession.” On the other hand, contemporary Tlingit and Nisga’a artist Larry McNeil’s Pop Art piece Vanishing Race 101 features Tonto popping Curtis in the jaw while saying, “Your ‘Vanishing Indian’ paradigm just doesn’t fit our Native epistemology.”

Mosa-Mohave | Photogravure | Size Unknown | 1909 | Peterson Family Collection

The exhibition at Western Spirit embraces these opinions and others, shedding light on the crucial role Native Americans played in Curtis’s endeavor, not just as subjects for his camera, but as guides, advisors, storytellers, linguists, and artists, reminding us that Curtis could never have navigated the world of the Indigenous West — and the many worlds within that world — without a great deal of assistance.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin, in 1868. His father was a Civil War veteran whose wounds led him to an evangelical calling, and he often took young Edward on his canoe trips from settlement to settlement while proselytizing.

The Curtis family moved to Port Orchard, Washington, in 1887, and by that time, the technological magic of photography had already fascinated the future artist. In the boomtown of Seattle, Washington, Curtis found work with another photographer before setting up his own shop. He had a knack for portraiture — for lighting and for what could be achieved artistically through the science of the darkroom — and soon, he became Seattle society’s picture-taker of choice.

The Oath | Copperplate | Size Unknown |1909 | Peterson Family Collection

In 1896, Curtis aimed his camera at Princess Angeline, the last daughter of Chief Seattle (Suquamish and Duwamish), who was selling shellfish from a shack by the shore. In 1898, three of Curtis’s images were chosen for an exhibition sponsored by the National Photographic Society, and two were images of Princess Angeline, The Mussel Gatherer and The Clam Digger. Princess Angeline made him wonder who else among the Western Native Americans might be willing to be photographed.

Curtis also had a fondness for mountains; he led parties of scientists and tourists up the slopes and glaciers of Mt. Rainier. In 1898, he rescued a party lost on the mountain. Among them were George Bird Grinnell, founder of the Audubon Society, and C. Hart Merriam, founder of the National Geographic Society. The following year, Curtis was chosen as the official photographer on the Harriman expedition to Alaska, and in 1900, he would accompany Grinnell to Montana, to the heart of the Blackfoot Nation.

In this new century, as Curtis watched the Blackfoot’s Sun Dance, a ceremony forbidden by the American government, the idea for The North American Indian was born. Disease was decimating Native American populations; settlers, the laws they brought, and the treaties they broke were confining Native Americans to ever-smaller reservations and severing them from their languages and traditions. Grinnell planted the idea that Indigenous peoples and cultures might vanish, firing Curtis’s passion and lending urgency to his mission.

Son of the Desert | Silver Photograph | 13.125 x 10 inches | 1904 | Peterson Family Collection

Heading east to raise funds for The North American Indian, Curtis visited Theodore Roosevelt and, after impressing Belle da Costa Greene, J.P. Morgan’s librarian, he secured financing for the project from the financial titan himself.

We think of Curtis as a dynamo, but he was patient and spent time with the people he visited from Alaska to Mexico. Curtis’s attention to the surviving scouts from the Battle of the Little Bighorn, for example, set in motion the historical reappraisal of George Armstrong Custer’s decisions and actions.

Curtis also did not work alone. He assembled teams of assistants, including Smithsonian ethnologist Frederick Webb Hodge; Alexander Upshaw (Apsáalooke), a graduate from the Carlisle Indian School; Adolph Muhr and Imogen Cunningham, whose darkroom contributions helped create Curtis’s aesthetic; University of Washington scholar Edmond S. Meany; and journalist and linguist Willian E. Myers. It’s helpful to think of Curtis as a collective that embodies the artist and his colleagues, sponsors, guides, subjects, and the ideas that floated in the zeitgeist of his time. In this light, we see the project and its legacy more clearly. And we understand how Curtis’s work all but vanished from public memory until it was rediscovered in a Boston bookstore warehouse in the 1970s.

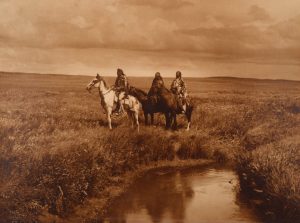

The Three Chiefs | Albumen Photograph | 11.25 x 15.5 inches | Date Unknown | Peterson Family Collection

The thousands of words in The North American Indian are also well worth a look, and the text is available in its entirety online. Curtis’s images are so striking that they often supersede the richly written text. Full of once-forbidden revelations about sacred mysteries, it has also been an important source in the revival of Native American languages and ceremonies. Take, for example, The Kwakiutl in volume 10; Curtis sets down origin stories and songs of gods and marvels with Kwakiutl words rendered phonetically, translated, and explained. Curtis credits Kwakiutl interpreter George Hunt for these insights and also admits: “Rarely is it possible to obtain such frank accounts dealing with a phase of their life which most Indians are very reluctant to discuss.” The stories Hunt tells, filled with love potions, escapes, and betrayal, are page-turners. The reader feels these might be stories that shouldn’t be shared, or perhaps tall tales that Hunt told to elevate his own status and wind Curtis up.

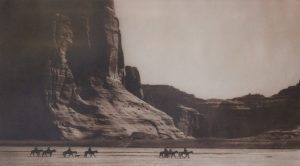

Canyon de Chelly | Photogravure | 1904 | Date Unknown | Peterson Family Collection

Because Curtis sought to include everything from images to ethnography and science, the strands of his work and thought are inseparable from one another. Unlike the works of trained scholars — who often disdained him — Curtis’s work resists academic detachment. The sheer plenitude of the volumes subverts the “vanishing race” impulse that initially drove Curtis and his contemporaries. A picture, especially one by Curtis, might be worth a thousand words, but the complexity of his tale takes all the words he — and we — can muster.

No Comments