06 Sep Fulfilling the Taos Dream

“Dream Yet Again” is the title of a talk that painter Jerry Jordan of Taos, New Mexico, will make to attendees at his upcoming one-man show, “Together Always Our Spirit,” opening at Legacy Gallery in Santa Fe on October 7. The title expresses a thread that weaves together stories of his 66-year-long career as an artist and how he arrived at a place he had dreamed of — including the simultaneous opening of his major exhibition and the release of Jerry Jordan: Together Always Our Spirit, an impressive career-retrospective book with a text by Phoenix-based art writer Michael Clawson.

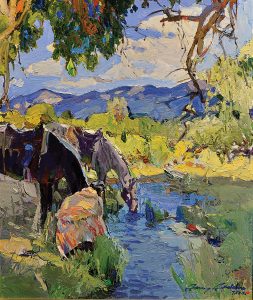

Brothers | Oil | 25 x 30 inches

It took 66 years of faith and the continual restarting of his dream for the artist to arrive at such a milestone. “The soul and spirit of Jerry Jordan are deeply buried in the fields, forests, and streams of Taos Pueblo and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains where, for over half a century, he has captured their beauty on canvas,” says renowned art dealer Jack Morris, acknowledging the artist’s importance. “Honoring the traditions of those who came before him by preserving this time in history, he has become an important contemporary painter of the American West.”

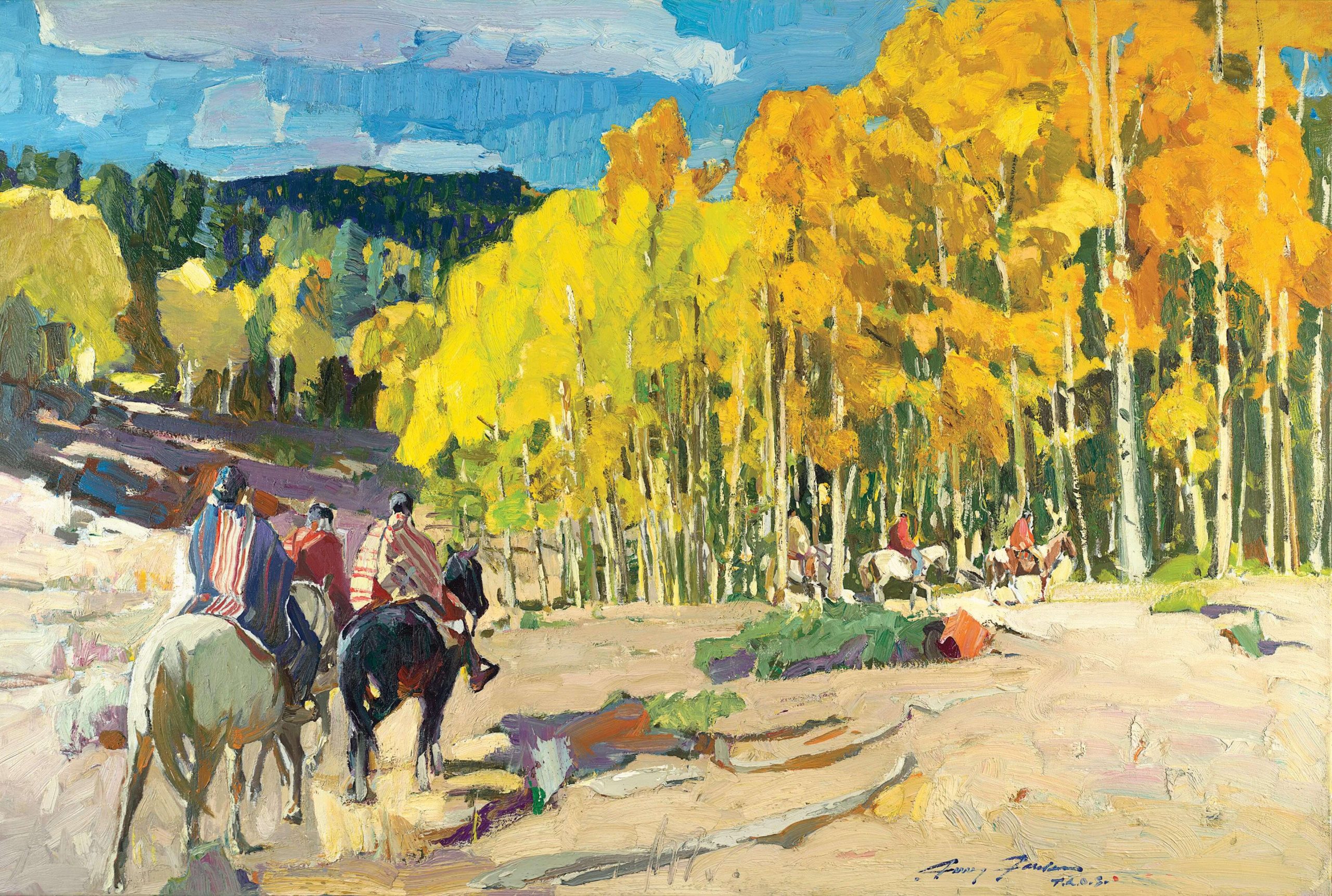

All Our Hopes Are Sacred | Oil | 34 x 60 inches

Brad Richardson, owner of both Legacy and Manitou galleries, agrees. “When we bought Manitou Galleries two years ago, I considered Jerry Jordan a hidden gem,” he says. “I’ve loved his work for many years and have watched him find his own voice, even though he’s surrounded by echoes of the Taos Founders. He expresses his unique interpretation of the surroundings that those who came before him loved and painted. While you can’t deny the influence of the Taos Founders on Jordan’s work, you can’t point to a particular artist that he tries to emulate. He’s influenced by all of them.”

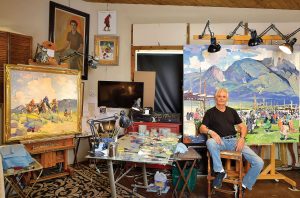

The spaciousness of Jerry Jordan’s studio in Taos, New Mexico, enables him to execute large paintings that are highly sought after by collectors. Jordan captures the magic of the New Mexico skies in and around the Taos region.

Jordan’s journey started early. His father Clarence built a studio onto their home for the young artist when he was just 16 years old. Participating in distributive education during high school allowed Jordan to pursue part-time vocational training; and he was self-employed as an artist during his senior year, with two requirements: that he must have a professional studio, and that he must make a profit from his art. Jordan excelled, making more than $4,000 by selling his art, a considerable sum in 1963 and equivalent to just shy of $40,000 today.

Jordan diligently applies paint to canvas, working on yet another joyous celebration of the people and places of Taos.

A major turning point in Jordan’s life came at the suggestion of a coffee buddy of his father’s, who said, “If your son wants to make a living selling pictures, then you should take him to Taos, New Mexico, where famous artists made a good living.” Soon the family visited Taos, staying at the Kachina Inn, which was filled with paintings by the artists his dad’s friend had referenced: The Taos Society of Artists, founded in 1915. Jordan was awestruck at the works on display by its founding members Oscar E. Berninghaus, Ernest Blumenschein, E. Irving Couse, W. Herbert Dunton, Bert Phillips, and Joseph Henry Sharp. Diligently studying each painting, he declared, “That’s what I want to paint like!”

Although Jordan employs a variety of brushes, he says, “I like feeling the brush and its resistance tension, and pay little attention to the brands.”

Afterward, Jordan explored the area and made profound connections between the locale and the art. “My first views of Taos were through the eyes of the Taos Founders. When I’d see something in real life, I’d think, that’s what Hennings would paint or there’s a scene Berninghaus would do.” He saw what they saw, recognizing places that had been important to each of the painters.

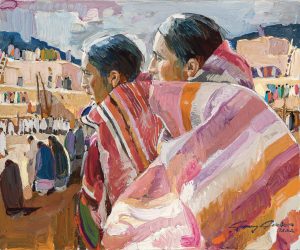

On another visit, Jordan was taken by seeing some of the men from Taos Pueblo, their torsos and heads shrouded with white fabric to ward off summer’s hot sun. When he visited in winter, he’d see them wrapped with colorful woolen blankets to keep themselves warm — a practice no different from when the early Taos painters portrayed them.

Jordan’s basic paint palette is based on the selection of colors used by John Sloan [1871-1951], a highly regarded member of the American urban realists known as the Ashcan School.

Reyna’s father Telesfor Goodmorning Reyna, 84 at the time, lived nearby in a 200-year-old home with ox blood floors. He became a regular model for Jordan, along with Joe Sandoval, known as Sun Hawk, a Tiwa elder born in 1900 who had also modeled for the original Taos Founders. These men became Jordan’s friends and mentors, providing encouragement. “Jerry, your dreams are already finished,” Jimmy Reyna once told him. “They’re just waiting for you to catch up to them.”

While living in Texas before moving to Taos, Jordan was showing his paintings with success at some of that state’s most respected art galleries: Connally, Altermann & Morris Galleries in Houston (thereafter Altermann & Morris in Houston, as well as Dallas and Santa Fe); and Bill Burford’s Texas Art Gallery in Dallas. In Taos, besides the Jordan Gallery and Jordan’s Magic Mountain Gallery, he showed with The Quast Gallery, Shriver Gallery, and Taos Gallery. Since 2006, Jordan has been represented in Taos by Parsons Gallery.

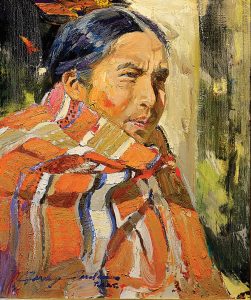

Cruz Lujan | Oil | 24 x 20 inches

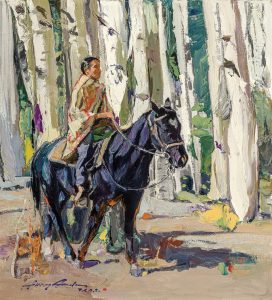

In the newly published book on Jordan, that gallery’s founder, Robert Parsons, makes a key distinction between Jordan and the artists he had originally strived to emulate. “Even though he has been inspired by the Taos Society, stylistically he is not like them at all. The most common comparison I hear is that his work looks like [E. Martin] Hennings, particularly his paintings of riders in the aspens. But I don’t agree because Jerry’s images are consistently better. Show me a 30-by-30-inch Hennings with a similarly sized Jordan next to it, and I will pick the Jordan anytime.”

Parsons’ quote affirms for Jordan that the 66-year journey to become the artist he is today was on track even though there were times it didn’t feel that way. One of his darkest days, when Jordan thought he might never be able to dream again, came after he closed Jordan’s Magic Mountain Gallery on Taos’s famed Plaza in 1998. “I was sitting back in Brownfield, Texas, thinking, ‘How in the hell did I end up back in Brownfield?’” he recalls. “We’d closed the gallery and we’d sold our house in Taos. My head knew why I was there — to look after my ailing parents. But my heart was questioning it. Then I heard my Lord say, ‘Jerry, I brought you back to a safe place to start over again.’”

Indeed, Texas proved to be a safe place, and Jordan was once again painting. His mother passed away five years later, and his father another two years afterwards. When his mother Melba was taken off dialysis, she said a prayer over each of her sons. “Her prayer was that I would be in a gallery that supported me so that Harweda [Jordan’s brother] could have the time to paint on his own. Within a couple of months, Bob Nelson [former owner] of Manitou Gallery in Santa Fe was showing my work,” recalls Jordan. That, he adds, “was nothing short of a miracle.”

Dreams Become a Source of Destiny | Oil | 28 x 26 inches

Both Jordan’s new show and the book have come as a result of him having had to dream yet again — as he did in 2002, when he and Harweda ventured back to Taos, renting the home and studio of painter and illustrator Frank Hoffman [1888-1958], sharing his 1,300-square-foot studio. By 2008, Jordan would buy the home and studio of American realist painter Lanford Monroe [1950-2000], where he and his wife Marilyn reside today.

Jordan’s signature on each painting is renowned for including the letters “T.A.O.S.,” followed by a red mark. The acronym stands for “Together Always Our Spirit,” as his new show is also titled. And the red mark? It came from a class he took with one of the Taos Six Artists, Rod Goebel [1946-1993]. Goebel encouraged Jordan to break free from doing what he knew how to do and, as Clawson relates in the new book, to “reach for something outside of himself.” Adds Jordan, also recounted in the book, “That’s when I transitioned to listening to the ‘download from God.’ I understood I have to listen to nudges … and intuitions. That’s when I began putting a red heart at the end of T.A.O.S. as a part of my signature … the heart later became a red dash.”

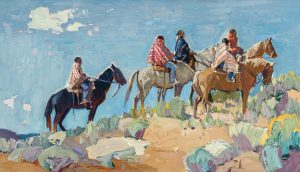

Time is Measured by Moments and Memories | Oil | 36 x 30 inches

For more than a year, Jordan has been devoutly painting for the Legacy opening and the book’s release. Many of the paintings that will be seen for the first time are a collector’s dream — major in size, featuring subject matter he referenced from a photo shoot he organized in October 2021 with members of the Taos Pueblo riding horseback. (He also created 66 original small paintings, one for each year he has lived in Taos, to be packaged with a deluxe limited edition of the new book.) Living in Taos, experiencing the scenery, the Pueblo, and its people, have provided a wealth of inspiration for Jordan – taking him full circle back to the inspiration he originally found there.

No Comments