06 Sep Formed by Fire

In medieval times across Europe, the goal of the court-appointed alchemist was to transform base metals into gold, that rarest of elements, deemed to exalt the wearer. Who could imagine that today, an artist originally trained as a master patineur, devoted to altering the surfaces of cast bronze through specially formulated patinas, would combine those same base metals in new and secret ways to transform sheets of bronze into luminous artworks?

Fluttering for You | Patinas on Bronze | 12 x 16 inches

Utah artist Nathan Bennett doesn’t play by the rules. He’s an exacting draftsman, rendering the world around him with a keen hand. He was inspired over three decades by other artists, especially renowned Utah painter and sculptor Dennis Smith. Sculptor Ray Jones at Wasatch Bronzeworks in Lehi, Utah, was an influential mentor in understanding patina. A disciple since the age of 18, Bennett has pursued this ancient art, unlocking the mystifying chemistry between fire and metal, and precisely how chemicals bond and react.

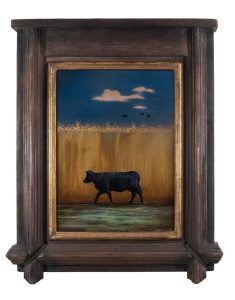

Roam | Patinas on Bronze | 16 x 12 inches

Bennett has an unusual studio nestled in the semi-wilderness of Mapleton, Utah, where you will never find canvas, oil paints, or acrylics. Rather, his workspace reminds one of the periodic table, with an array of chemicals including iron, silver nitrate, zinc, cobalt nitrate, titanium oxide, copper, and even sulfur, to name just a few. It’s a wizard’s blend of precious ores and elements that he brings to life under the hot blue flame of a propane torch. These metals, applied in various ways, including airbrush, spray bottle, and brush, bond immediately to bronze panels, so the artist has to control every single second.

Still Glowing | Patinas on Bronze | 14.5 x 23.5 inches

Surprisingly, Bennett relies on a considerable measure of unpredictability despite the control required for his art. Combining or overlapping metals creates a range of colors that glow as if lit from within, and although each metal has different properties, they “know each other,” according to Bennett, and share many commonalities like sheen and melting points. The marriage of these elements results in surfaces that often shimmer and dance before your eyes, while others produce a subtle, smoky atmosphere. From the darkest black to the purest white, Bennett’s color palette is limited only by his imagination.

Silence | Patinas on Bronze | 14.5 x 23.5 inches

Although once a sculptor, he now prefers to work in two dimensions, and he rarely creates patinas for others.

“Those days are gone,” says Bennett. “I’ve hired an apprentice to take over the contract work through my company, Signature Patinas. My joy, my only purpose from here on out, is to paint.”

Evolution | Patinas on Bronze | 27 x 18.5 inches

Although Bennett’s moonlit or misty landscapes may seem like actual places to some, his forests, lakes, trees, birds, butterflies, vintage locomotives, and majestic creatures in the wild are imagined; they are manifestations of an inner world, a place lived over a lifetime and filled with sorrow and awe. One example is Silence, a patina painting of a lone wolf padding through the snow. His gaze meets the viewer’s eyes head-on. The animal is at once supreme and fearless. At the same time, he seems vulnerable, alone in the cold, white flecks of snow upon his dark black fur, unprotected against the elements.

“The wolf is a mirror of a battle with myself,” says Bennett wistfully. “It’s me, persevering. Or, if you like, the wolf can be you. Whatever part you recognize.”

A major shift in Bennett’s work today is due to the discovery of large metal panels that are more resilient. Bronze, which is soft, has a tendency to warp, so controlling the temperature and stability of larger works was challenging. By using aluminum, the artist can accept commissions as large as 4 by 6 feet. Prior to this time, his largest size was 24 by 48 inches.

“Now,” he says, “I have more space to express myself.”

We Gather Here Today | Patinas on Bronze | 48 x 48 inches

The artist often chooses to express his love of trees — trees bursting off the surface in bright shades of copper and gold. Trees in bloom, full of leaves, in connected canopies, and in stark, nighttime silhouettes. “Trees experience the world like we do,” Bennett explains. “They take root, grow, weather the seasons, and die. They bear fruit and nurture. Trees are us. The trunk is like the body, but we cannot see the soul. Yet, we know it’s there. Trees remember.”

Trees, it appears, serve as a vehicle for Bennett’s emotions.

Collectors Racheal and Nathan Stahlman, who own eight of his patina paintings, say it best: “To us, the tree is an image of strength and perseverance. Looking at one of Bennett’s paintings keeps us going. It’s a metaphor for the will to succeed; in a way, our daily dose of inspiration.”

Time to Go | Patinas on Bronze | 48 x 48 inches

Blue Rain Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico, debuted 10 new pieces by Bennett in a solo show that opened on September 27 and continues through October 11. Gallery owner Leroy Garcia firmly believes that Bennett is a pioneer and that his innovation in a unique field is as important as the technical skill required to produce the work.

“His control of the medium, allowing him to create exacting imagery, is even more demanding than the skill of a fine watercolorist,” says Garcia. “After all, we’re talking about acids, alkalines, metals, and more, applied through the intensity of heat. What is most remarkable about each painting is the optical illusion of movement and depth. Translucency and reflection make the view different from every angle. These paintings seem alive.”

In a conversation with colleague Bryce Petit, a sculptor who understands patinas, Bennett was asked what his intention was. Explaining that his works are also studies in contrast, he pointed out that, “We cannot see the light without the dark.” In many ways, Bennett’s paintings are metaphors for life.

“In the end,” says Bennett, “mostly what I paint is hope.”

No Comments