06 Sep Safeguarding Tradition

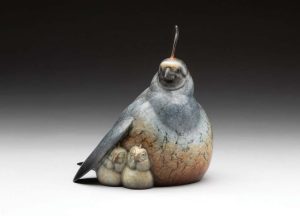

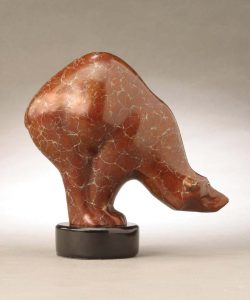

Among the most common reactions to Josh Tobey’s sculpture, aside from smiles, is the question: What is this made of? Is it stone? Ceramic?

The surface is so smooth — with rich, delicately gradated hues and often marble-like patterns — that bronze is not what first comes to mind. But it is bronze, cast by a foundry in the traditional lost-wax process.

Under My Wing; Tobey and his wife Jojo with life-sized wolves, Heart and Soul. Jojo, who handles the business side of Tobey’s art career, is “my greatest strength,” he says.

As a second-generation sculptor who carries on his late father’s deep commitment to the medium, Tobey has dedicated many years to creating elegant wildlife forms that elicit an emotional response, and to ensuring the exceptional finish of each piece. This is where a major problem has emerged in recent years — a serious issue in the fine art bronze casting industry that Tobey has taken steps to address.

Inherent in the realization of any bronze work is that, regardless of the artist’s talent in conceiving and carving a clay or wax form, the final artwork is entirely dependent on a team of highly trained foundry workers. “We need skilled people capable of faithfully producing our work to our intended design,” Tobey says. Or as Pierce Tome, co-owner of Astoria Fine Art in Jackson, Wyoming, puts it, “It takes an army to produce a bronze.”

This has been true of bronze since the first sculpture was cast some 2,500 years ago. In recent years, however, a confluence of economic and other factors has led to a sharp decline in the number of fine art foundries in the American West, with a challenging snowballing effect for all parties involved — sculptors, galleries, art museums, collectors, and the foundries themselves. Costs have skyrocketed, and the turnaround time for a single piece of bronze art, previously between eight and 16 weeks, can now take as long as a year or even two.

Tobey’s response was to design and build his own foundry and gather a dedicated, skilled team to produce his and potentially other artists’ work. The 12,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art facility in Enterprise, Oregon, was named The Mountain Fine Art Productions in part because conceiving, planning, and building it has been a several-year journey. “It feels like we’ve climbed a mountain,” Tobey says. Construction was completed in August 2024, with a celebratory grand opening set for September 7 and annual invitational shows to be held in the space. “I did not step out to be a foundry owner,” the artist says. “But I feel like we’re up against a wall in this beautiful industry.”

Tobey with The Conspirator Bears, installed in Jackson, Wyoming. From the start, the sculptor has infused many of his creations with charming, human-like personalities and a sense of whimsy.

Even as a child, Tobey was aware of the challenges of working with bronze foundries. He remembers his father and artistic mentor, acclaimed sculptor Gene Tobey, complaining about foundries not getting his pieces right. Gene taught ceramics at the college level when his son was young, and his bronze work was known for smooth finishes and exquisite patinas. Josh learned early on that achieving these qualities required the artist to spend significant time at the foundry. The family lived outside Santa Fe near Shidoni Foundry, and he and his father would ride horses to the facility to check on his father’s work.

The bronze Timid Bear is among Tobey’s earliest pieces. The sculptor has poured passion, energy, and commitment into The Mountain Fine Art Productions, in Enterprise, Oregon, in response to the shrinking number of fine art bronze foundries in the Western U.S. today.

Aside from picking up on his father’s frustration, Tobey says, “It was a wonderful childhood, growing up around artists, Dad’s friends.” His father shared a birthday with the well-known Santa Fe painter Frank Howell and the two families would often celebrate together. Tobey recalls his father telling him, “As an artist, you absorb things. You learn to be an artist by being around art.” For Josh, this included easy access to numerous Santa Fe galleries and art museums at a time when Western and Southwestern art was gaining ever-broader collector interest. By the time he received an art degree from Western Colorado University in Gunnison, Colorado, in 2000, the art market boom of the 1980s and ’90s had led to the establishment of a number of new foundries.

For six years following graduation, Tobey worked in Gene’s studio — which by then was in Texas — gaining knowledge and skills while helping his father as the elder sculptor’s health was declining. (After Gene’s death, his wife, artist Rebecca Tobey, continued his legacy by producing work in his style before moving into her own art.) One thing that especially impressed Tobey was his father’s insistence on respecting the work by finishing it beautifully.

Soon, Tobey began creating his own art, and in 2011, he and his wife Josephine (JoJo) moved to the Loveland, Colorado, area, where there were four foundries, now reduced to three. Today, the couple’s home and studio are on 80 acres outside Estes Park, surrounded by a national forest and visited by wildlife, including elk, deer, and bears. Because the Tobeys travel often — the artist had 13 shows around the country this year alone, along with frequent trips to the new foundry in Oregon — the location provides access to the Denver airport while offering privacy and serenity.

Long ago with his first sculpture, Timid Bear, which he considered a self-portrait, Tobey discovered he could suggest compelling, human-like emotions through an animal’s expression and gesture. These whimsical abstracted pieces and representational wildlife works have made him a best-selling artist at Astoria Fine Art and other galleries. “Life is hard enough, and art can be something that just makes you smile,” Tome says.

The smooth bronze surface of Tobey’s sculptures is the most challenging texture for a foundry to achieve. Because patination is also a highly undervalued art, the artist did most of his own patinas in his studio, with JoJo’s help, for several years.

In the newly built foundry, Tobey and his crew will have ample space and excellent conditions for producing large works, such as the life-sized Sheep.

Over the years, Tobey has had his work cast in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, California, Wyoming, and Oregon, moving on when turnaround times became too long, the quality of finish work was unsatisfactory, or when facilities closed. While foundry owners’ profit margins have never been large, since 2020 the cost of materials has risen exponentially. Owners are aging and retiring, and foundry facilities and land are often valuable real estate and sold to other interests. At the same time, foundry workers’ pay has generally not kept up, so when higher-paying work comes along, many leave the industry. As more foundries close — including one in Cody, Wyoming, that burned down in the summer of 2024 — and are not being rebuilt, artists turn to the remaining foundries, creating greater backlogs. “It’s really a tough situation,” Tobey says.

Tobey and crew with The Mountain in clay, so titled because it was the first monumental sculpture cast at The Mountain Fine Art Productions.

For galleries, when a popular sculpture sells and cannot be replaced in a reasonable amount of time, it is a major loss for the artist, gallery, and collectors. “In the art world, we have really good years and lean years, so getting replacements for the gallery in those good years is important,” Tomé says.

Tobey, a prolific artist, began thinking about alternatives several years ago and eventually settled on building a foundry in an area of Oregon known as a bronze production hub. Already working with the talented Oregon-based patineur Bart Latta — “We jam like musicians,” Tobey says — he hired him as part of The Mountain’s carefully selected crew. The foundry will pay a living wage, encouraging workers to stay.

The artist in the studio sculpting The Mountain, a resting moose.

The facility also offers less challenging working conditions than most, including an air-conditioned metal area for welding and a large patina room with a 20-foot-high ceiling to accommodate monumental works. It is “beautifully designed to function as a foundry,” the artist says. Without getting overbooked, he hopes to be able to offer services to other sculptors “as we have time,” he says, adding that making such a dream possible will be an autonomous team, a collective of workers who know their jobs and do them well.

Tobey applies patina to Heart of the Mountain, his first monumental piece and the first sculpture he did after his father died in 2006.

Tobey knows about good teamwork. All along, he has had his own efficient little crew: himself and JoJo, who handles the business end of his art. “I make and lift heavy objects, and she does the smart part,” he says. “It’s my great strength in my career to have a partner like that.” In the larger art world, his goal is lofty yet vital: to “help preserve the legacy of the lost-wax casting process and the skilled tradition of American fine art bronze sculpture production.”

No Comments